A “History’s Reformers” Unit Celebrates Activism

A MiddleWeb Blog

My absolute favorite unit, a “reformer from our history” research paper and campaign, is the only one I’ve done every spring through seven years of teaching U.S. history to eighth graders.

My absolute favorite unit, a “reformer from our history” research paper and campaign, is the only one I’ve done every spring through seven years of teaching U.S. history to eighth graders.

It focuses on resilience, activism, determination. It celebrates rather than eulogizes.

Through their research, students see themselves in history in new ways, often choosing an activist from the past who reflects their passions and background. As one said, “The reformers used their power to save the world, not destroy it.”

Lasting the better part of a quarter, this unit epitomizes the hope that keeps me teaching, the spark that drives us day by day, person by person, toward the beacon of “a more perfect union.”

Where’s the Dessert?

In the past, I’ve written about the browsing students do to select a reformer, the outline organizer that makes rough drafts fun to read, and the changemakers questions that spice up a research paper.

Each of these articles relates to the traditional research process of finding sources, taking notes, crafting topic sentences and thesis statements, and supporting arguments with evidence – steps I love. In fact, I once wrote an article about how much I adore making research notecards.

That said, the element I love most comes after we’re done with all of these steps. The reformers paper is the main meal – a hamburger, or veggie burger, or grilled portobello mushroom, or whatever fills you up. The reformers campaign, on the other hand, is the dessert, and it comes in two parts.

Part 1: The Campaign Statement

As students are finishing the final drafts of their research papers, I ask them to list confidential preferences of whom they could work with productively (or not-so-productively) for the group portion of this reformers unit. Just because someone is your best friend does not mean you have a productive working relationship, I remind them!

Usually I can form groups of three to four that give everyone at least one classmate they wanted to work with. I hesitate to have students form their groups, especially if we’re learning online, because I don’t want anyone to feel left out.

As students work on the one-page campaign statement, which takes a week or so to complete in class, they follow steps 1-4 in groups:

1. Share information about your reformers – everyone should read everyone else’s research papers.

2. Imagine which current cause your reformers might REALISTICALLY support, given what you know about them historically.

a. Look through your current events notes or browse online to imagine a reasonable cause.

b. Check in with me once you have an idea.

3. Find sources about your cause – at least one contributed by each of you from ProQuest or other reliable sources. Annotate at least two pages of each source.

4. Create a Works Cited list in NoodleTools.

The hardest part of this stage for students is deciding which current cause their group of fairly random reformers might all support. I spend a lot of time consulting with each group and driving them to think deeply. If they are stuck, I suggest they flip through their current events notes from our daily articles and weekly presentations or browse through a national newspaper to stir their thinking.

Here are some of the issues students have picked for their reformers, all from this year’s campaigns:

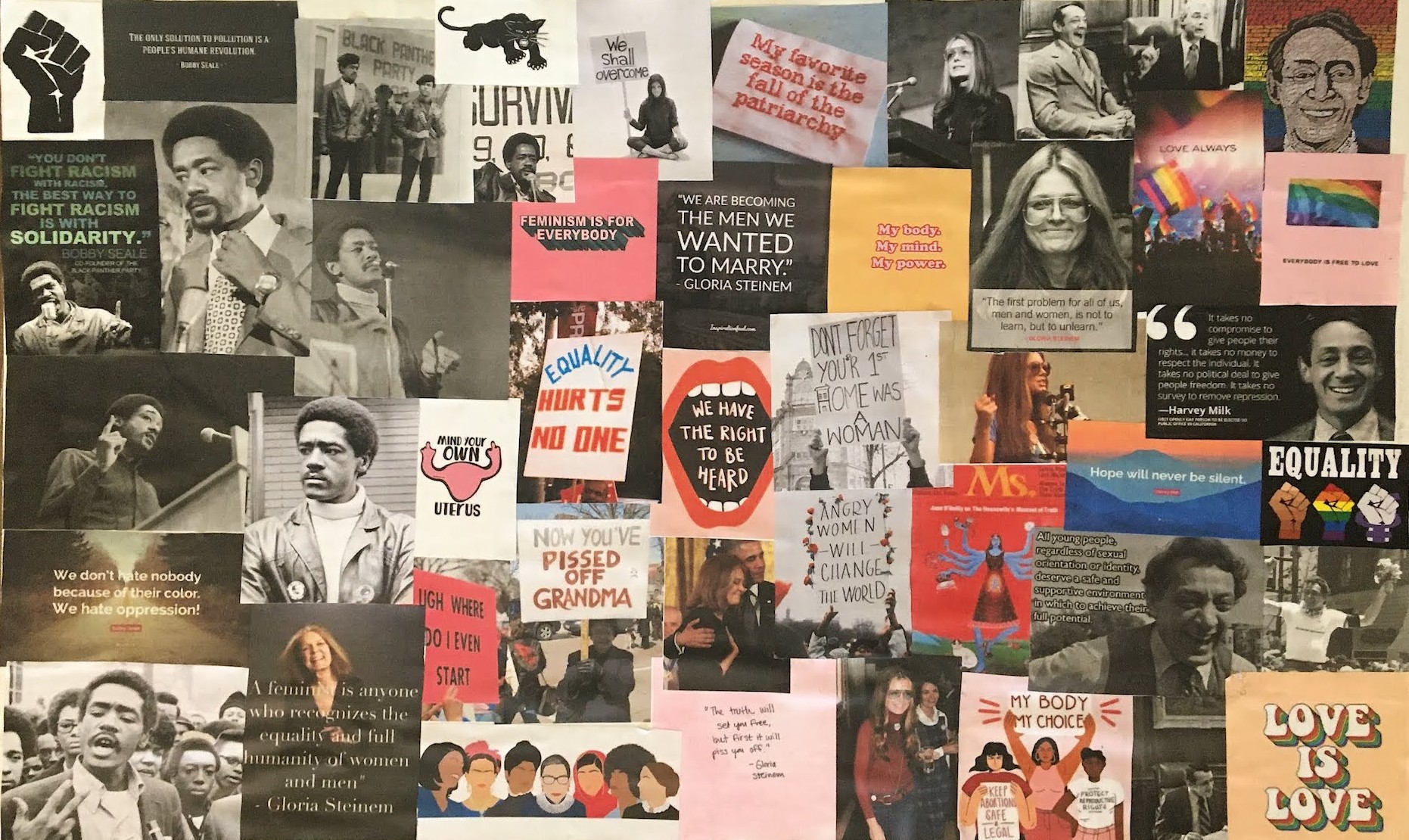

► Harvey Milk, Bobby Seale and Gloria Steinem: “Yes to the ERA”

► Nellie Bly, Huey Newton and Sandra Day O’Connor: “Diversity in Universities”

► Rachel Carson, Dolores Huerta and Yuri Kochiyama: “Getting restitution for the generations of Native Americans impacted by the large amounts of toxic waste left on their reservations.”

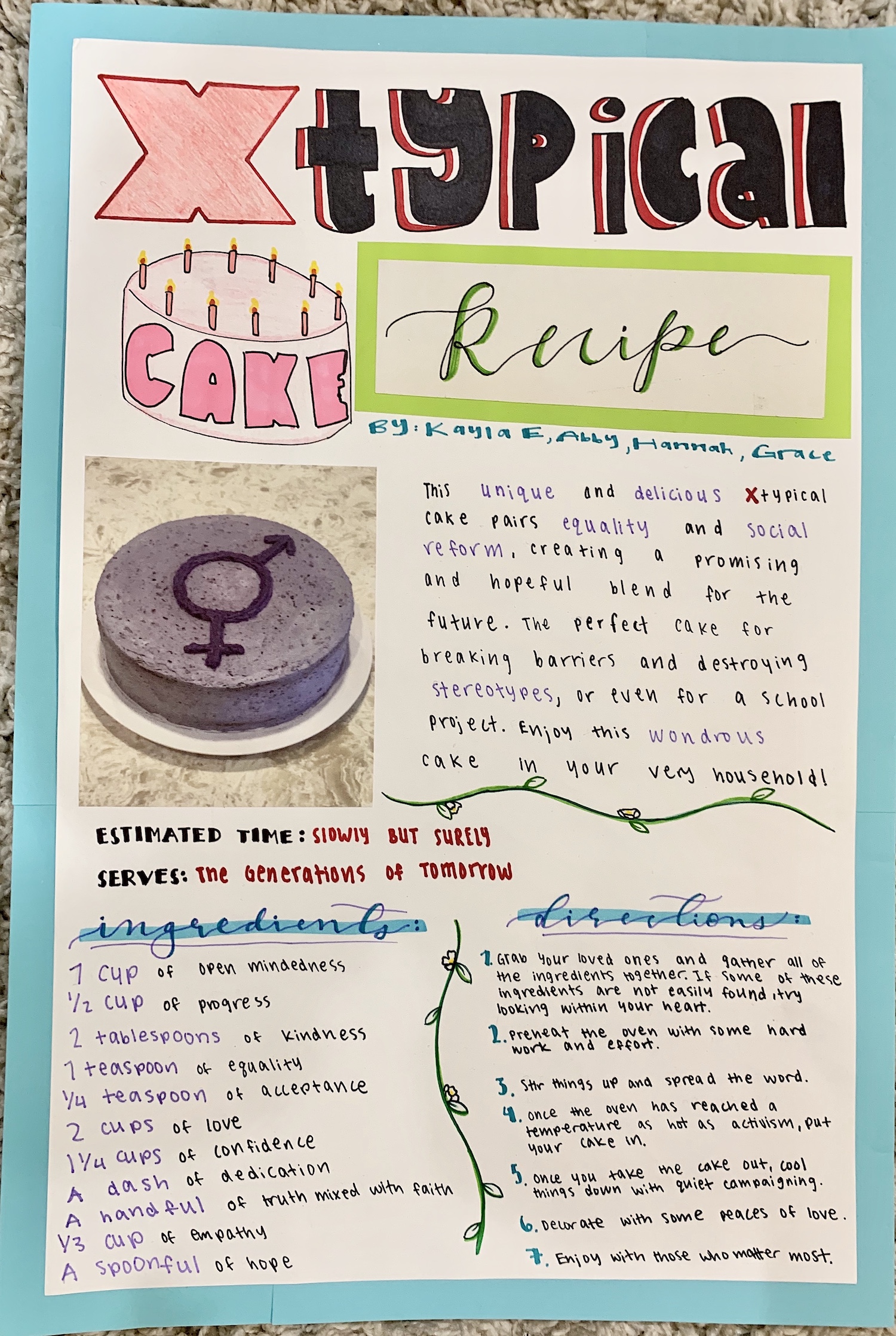

► Jane Addams, Marian Wright Edelman, Carrie Nation and Alice Paul: “X-Typical: Preventing the Establishment of Stereotypes and Gender Roles in Youth”

Once the group has finished finding sources and making a bibliography, they get to create their campaign statement. It’s a one-page overview, and the rubric requires that it:

✻ Explains what your cause is and why your reformers would support it, reflecting accurately what the reformers would actually think about the cause (5)

✻ Tells, in a persuasive way, what you would like to do about your cause. This idea should be realistic, feasible and appealing (5)

✻ Includes relevant and interesting information about each reformer (3)

✻ Fits on one page and looks nice (2)

Students often use Canva, which they learned earlier in the year when showcasing quotations about social reform for a community impact project. Others experiment with Google Slides, PowerPoint or even Adobe Illustrator.

We post the finished statements on the wall or in a shared Google Drive folder for students to do a gallery walk. For this year’s virtual version, the in-class assignment read:

1. Look through at least three other groups’ campaign statements.

2. For each of the three, list the group members’ names and describe specifically something you like about the statement. This is a chance to be generous to your friends and classmates, and I may even anonymously pass on your compliments to them!

Part 2: The Campaign Product

If the campaign statement feels like a rich dessert, then the campaign product seems like the butterscotch sauce on top!

This creative product is a chance for students to use their talents and skills in ways they find most fun. Yes, their products have to be meaningful, but the rubric guidelines are deliberately spare, with only three criteria:

✻ Product(s) are complex enough to communicate the campaign issue thoroughly (5)

✻ Product(s) convince us fully of the merits of your campaign (5)

✻ Product(s) are creative, clever and memorable (5)

Usually I start this final step of the unit by handing out Roger Taylor’s AHA! Product List and Grid, which I’ve used since I started teaching. It’s not very digital, but students literally wonder out loud at some of the more unusual options, such as pamphlet, papier-mache or pop-up book.

As with the campaign statement, the groups consult with me as they plan, whether in person or (more recently) in Zoom breakout groups. If a product is on the small side – such as a delightful Buzzfeed quiz one group put together on “What World-Changing Female Reformer Are You?” I’ll ask them to do a second one also, in this case a sophisticated drawing of one of their reformers.

Products run the gamut from podcasts to Powtoon videos, posters to debates. Here’s a handful of this year’s examples, some of which required students to shift from physical to digital creation as we transitioned to online learning:

• An illustrated field trip permission slip

• A border wall assembled in Minecraft

• A video of an infinity cube with art and quotations

• A cake recipe with “1 cup of open mindedness” and “a dash of dedication” as ingredients and a direction reading, “Stir things up and spread the word”

Their peers’ compliments included:

• I liked their idea of doing a comic book because it got their point across in a fun and interactive way.

• I think that their slides were really fun, and I liked how it was sort of choose your own adventure, but still very informative.

• You can tell that there was an insane amount of effort put into this visual and it really shows. This is such an incredible drawing.

Warming My Heart

Ultimately, this reformers unit is inherently differentiated – first by students’ choosing a person who resonates with them and then by illuminating their group’s cause through products unique to them.

As I write about these projects in the middle of summer, remembering the joy in students’ eyes when they realized they could create whatever they wanted, such freedom still thrills me.

And the whole unit, from soup to nuts, from research paper to campaign statement to campaign product, reminds me of what a student recently observed about my entire U.S. history and civics class: that it is my not-so-secret mission to show eighth graders that they can change the world.

Guess my secret’s out!

Browse Sarah’s many articles and reviews for MiddeWeb here. For other writing about history and more, visit her blog.

So cool! I LOVE it when we bring history into the now. When we don’t, kids somehow get the idea that we “fixed” issues that really haven’t been fixed at all. Your project marries then and now in an engaging way that demands critical thinking. KUDOS! Thanks for sharing!

Rita, this means so much coming from you! Thanks for commenting and for encouraging connections.

This is a nice insight into student creativity and teaching. I wonder if you know who said, “The reformers used their power to save the world, not destroy it.” I can’t seem to find the quote attributed to anyone and would like to reference it in a sermon reflection.

Hello, Rev. Jacobs –

Sarah Cooper is directly quoting one of her students in this passage. It also appears in her book, Creating Citizens, on page 16. Learn more about her book here.

Susan at MiddleWeb

I love this project! I have the book, but is there a list somewhere of potential reformers that could be used?

This Wikipedia page offers an extensive list of American Social Reformers (A-Z). The links lead to individual entries and you can ‘mouse-over’ a name to get a popup summary. A good place to start! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_social_reformers

Nicole, thanks for this enthusiasm! I still love this project, too, and I’ll PM you the list right now :) This year I encouraged students to use AI in bits, too, helping brainstorm keywords and titles (with attribution!).