Media Literacy: Teaching Kids about Political Ads

A MiddleWeb Blog

So here we are: airwaves (and social media) are already full of ads by candidates running for office. Most likely you’ve seen them. Perhaps you’re turned off by them.

So here we are: airwaves (and social media) are already full of ads by candidates running for office. Most likely you’ve seen them. Perhaps you’re turned off by them.

As a media educator, I see it as my job to help educators and their students analyze these unique persuasive messages using a “media literacy” critical viewing lens.

Whether you’re teaching in your physical classroom, in a virtual setting, or some blend of both, I hope you’ll take some time this fall to advance your students’ citizenship skills and their understanding of how office seekers and their political organizations use the techniques of persuasion and propaganda to sway votes and gain power.

You might be a social studies teacher, an English teacher, or an educator tasked with teaching consumer science or marketing. Whatever the case, this background and these resources can help.

TARGET AUDIENCE. Like all other products, candidates have to position their ads to reach their intended audience. For example, many candidates like to run their ads during local news (have you noticed?) [See Why Political Advertisers Double Down on Local TV.]

But let’s say you (the candidate) want to reach African American voters. You might decide to have your “media buyer” purchase time during “Black-ish” (ABC). Last fall, sports programs, like NFL games or a MLB playoff or World Series game, attracted a large Black audience. (Source) Might the resumption of these sports under pandemic guidelines also mean the return of political ads in these programs? Only time will tell.

SOCIAL MEDIA. In the meantime, candidates are now using popular social media platforms to also reach their target audiences, many of whom are young. According to a recent post on the American Bar Association’s website: “there are a few major platforms that dominate the (political ad) landscape – Facebook (and its subsidiaries WhatsApp and Instagram), Google (and its subsidiary YouTube), and Twitter.” (Source) Recently, Facebook and Instagram announced they will allow users to turn off political ads on those platforms.

NOTE: When Donald Trump ran for president in 2016, his first ad ran on Instagram and was only 15 seconds long. It was not required to include the disclaimer “I’m Donald Trump and I approve this message,” because it was not broadcast.

How to Watch & Analyze a Political Message

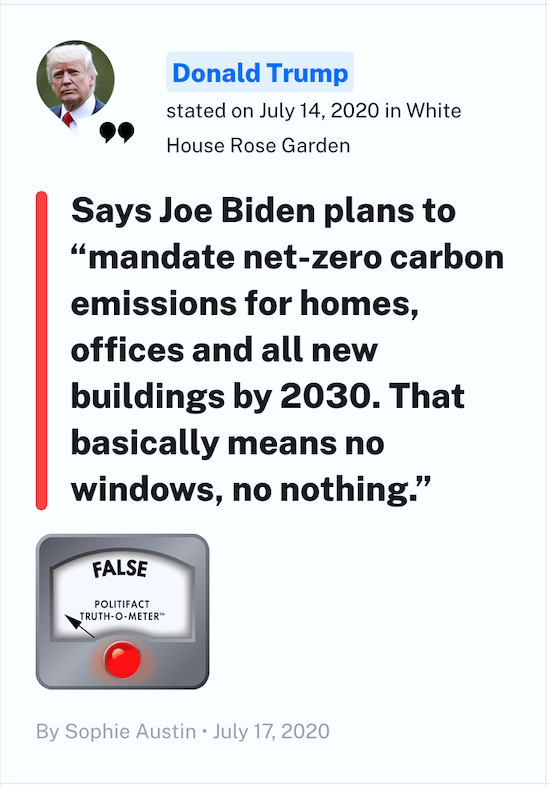

Candidates will say anything in their ads. They will even lie. Yes, lie. How is that possible, you might ask? Political advertising is considered free speech and thus it cannot be censored. Broadcasting stations (which reap millions of dollars in ad revenue from political ads) cannot refuse to air them. Would they screen or fact-check them if they could?

You may recall that in March, a pro-Trump Super PAC demanded that TV stations in key battleground states (Florida, Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania) stop airing an ad (produced by a Democratic Super PAC) that said President Trump called the coronavirus a hoax.

Several fact-checkers said the President did not label the virus a hoax, but instead was referring to what he claimed were efforts by Democrats to politicize the virus. (Source)

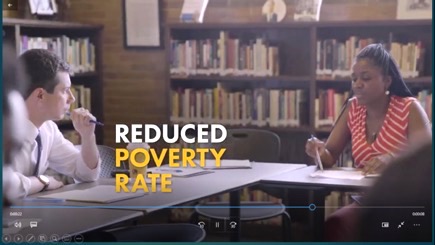

When watching an ad, pay attention to the words on the screen. Oftentimes, words will be superimposed on the screen to amplify what a candidate or narrator is saying.

For example, when Pete Buttigieg was running to become the Democrat presidential nominee, one of his ads superimposed the words “Reduced Poverty Rate’ referring to the time he was the mayor of South Bend Indiana. Factcheckers disputed that assertion.

Students could also be assigned to VERIFY assertions and other claims made in ads. Today, many fact-checking organizations are already investigating these ads.

Other visuals that might appear in these ads include symbols, like the American flag, the military, or children and teachers in a classroom. The people who advise politicians know: visuals often communicate better than words.

In 2002 researchers revealed some of the tricks and techniques. For example, primary colors (red, white and blue) were used to promote patriotism. Dressing a candidate in certain clothes translated strength, vigor or authority. Opponents are often portrayed in darker colors suggesting sinister purpose. (Source: The People’s Choice: Digital Imagery & The Art of Persuasion)

Students should consider why these symbols exist in political ads – what’s their purpose? [For more about this, see Civics 360: Bias, Symbolism and Propaganda.]

Editing and the manipulation of video is another tool campaign ad experts use in the production of ads. Have students watch this short segment from CNN’s special “The Campaign Killers” in which an expert details some of the techniques used in previous elections.

Sound is also an important element to consider in the production of campaign ads. The use of music, for example, has a long history in politics. [See: Songs of Politics & Political Campaigns] Music can be used to convey a message or a mood, especially to make the viewer feel good about a candidate or issue.

One strategy you might employ with students is to have them close their eyes and listen to an ad that uses music. Afterwards, ask them to describe the music. How did it make them feel? Have your students listen to this ad, The Country I Love, which was Senator Barack Obama’s first televised message when he began running for President. Did they notice the music?

See also: Political Ad Analysis Worksheet

Manipulating the Image

There are predictions that “deepfake” videos will be employed during the Election 2020 cycle. Deepfakes are cleverly edited videos that electronically copy a person’s face and then, using previously recorded sound, make it appear that the person said something they never really said.

In 2019, a deepfake video of President Obama appeared in social media and elsewhere. The producers were wise to explain how the video was made, but also to warn that others might exploit the technology as we get closer to November. [Watch the Obama deepfake video and explanation here.]

Deepfakes make use of algorithms that process images, video, or audio of real people – such as celebrities and politicians, for example – in order to synthesize the content (to have) them doing or saying things they did not. – Natasha Stokes, Techlicious.

How would your students know if a video is a “deepfake”? More than likely, they would first see it on their social media feeds, and they might believe it’s real without question. But questioning and verifying authenticity should be the goal. See also: How to Spot a Deepfake Video

Other areas to explore with students

Propaganda Techniques. This website breaks down the various “techniques of persuasion” and provides video examples of each technique from previous presidential candidates’ commercials.

Dark Money. Do students know what the phrase “dark money” means? They should. They will probably encounter that phrase in many news stories about political advertising in 2020. [See Lesson Plan: Dark Money with links to videos.]

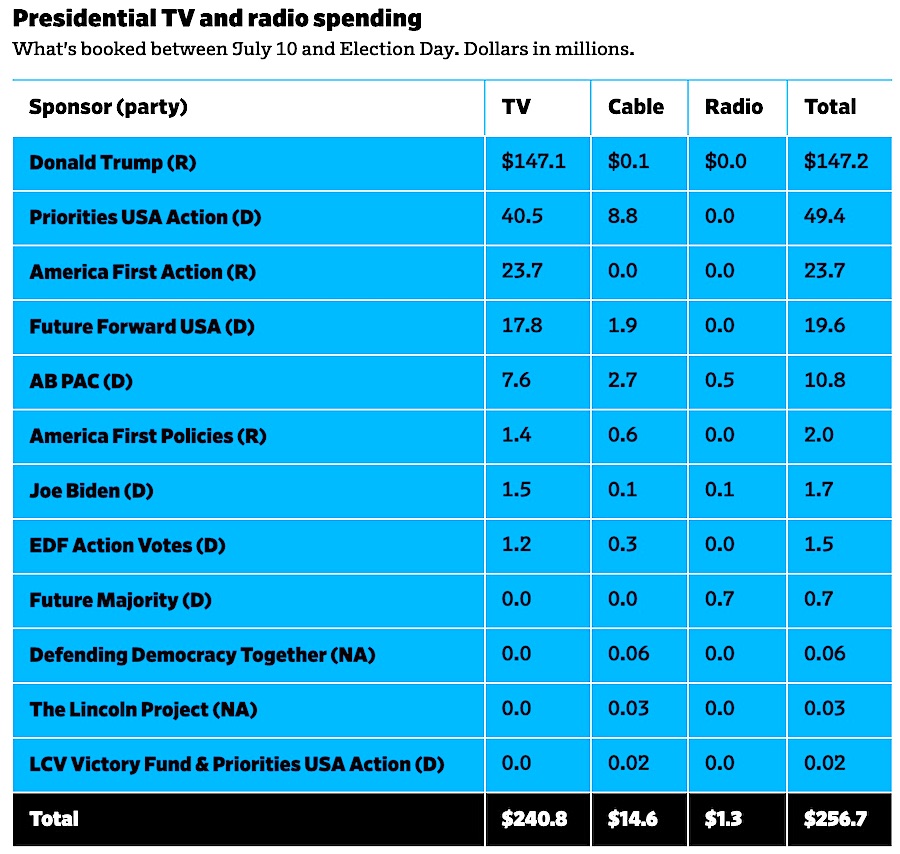

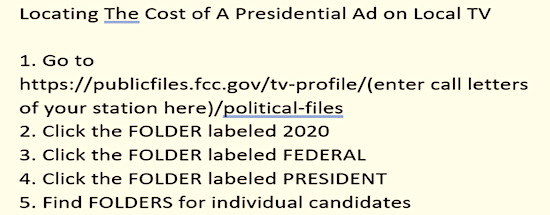

The Cost of Ads. Who benefits when politicians buy time on local TV? The primary beneficiary is the television stations themselves. This time of year, they will reap millions of dollars in ad revenue. Your students can conduct a search (using the FCC’s website) and examine exact contracts politicians and their buyers have with these stations and their owners.

Follow the procedure outlined in this graphic:

Advertising and political experts are predicting record spending this election season, as much as $6 billion – up from $4.35 billion during the last presidential contest. As we brace for this tidal wave it makes good common and civic sense to prepare our students and future voters for this unique form of analysis and critical thinking.

Recommended resources:

Political advertising grows on streaming services, along with questions about disclosure

https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/03/politics/streaming-services-political-ads/index.html

The People’s Choice: Digital Imagery & The Art of Persuasion (Lesson Plans)

https://frankwbaker.com/mlc/the-peoples-choice-digital-imagery-the-art-of-persuasion/

How to Master the Political Art of Symbolism

https://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2013/12/18/255225472/how-to-master-the-fine-art-of-political-symbolism

Political Advertising on Social Media Platforms

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/voting-in-2020/political-advertising-on-social-media-platforms/

The Evolution of Political Ads (2013 video)

https://www.cnn.com/videos/politics/2012/10/17/natpkg-orig-political-ad-evolution.cnn

How Political Ads Get Inside Your Head (2014 Video)

https://www.cnn.com/videos/bestoftv/2014/11/01/how-political-ads-get-inside-your-head.cnn

Help Students Analyze the Impact of Political Ads (MiddleWeb)

https://www.middleweb.com/41401/help-students-understand-the-impact-of-political-ads/

The Role of Media In Politics (Media Literacy Clearinghouse)

http://frankwbaker.com/mlc/media-politics/

Feature image: NBC News

For educators seeking an online database/collection of current political ads, try Google’s site here https://transparencyreport.google.com/political-ads/region/US?hl=en