Examining EL Education with an Anti-Racist Lens

A MiddleWeb Blog

When I started my blog and podcast, I vowed that I would not be political because I do not want to ostracize my readers and listeners.

When I started my blog and podcast, I vowed that I would not be political because I do not want to ostracize my readers and listeners.

But I’ve come to realize that because I have your trust, I have to use this platform to do the right thing, which is to be brave and host uncomfortable conversations about education and race relations.

I am sharing highlights from my podcast conversation with Dr. María Cioè-Peña because I need to confront this issue and realize that things I may be doing – even with the best intentions – might drive a wedge between students and the school or students and their families.

I know that you deeply love your students. So, because of that love we all have, I want to share María’s framework for being anti-racist.

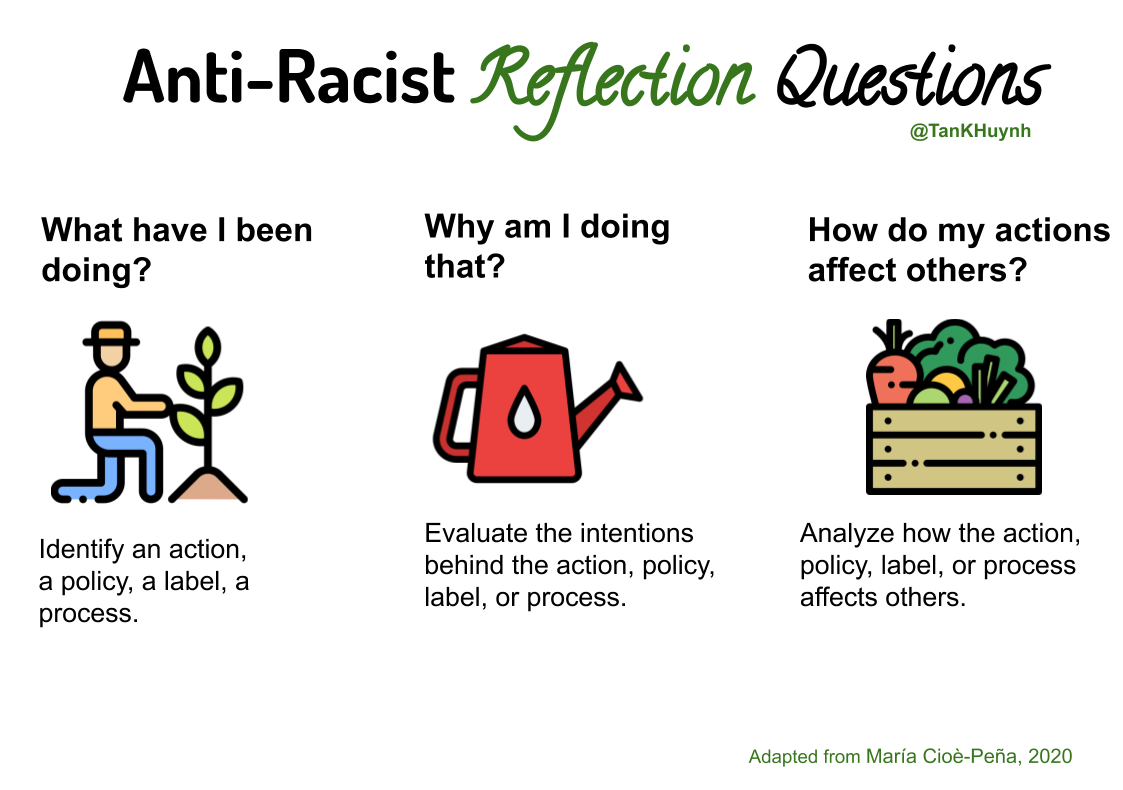

Instead of a list of what to do and actions to avoid, she recommends that we continually reflect on our practice. To help us do that, she offers these three self-reflection questions:

- What have I been doing?

- Why am I doing that?

- How do my actions affect others?

1. What have I been doing?

To model this process for you, I will take a practice that many people are still using in their schools: the English-only policy. When you run this policy through the first question, we see that we have been punishing students for not using English.

Punishment might be in the form of lost participation points, detentions, being sent to an administrator’s office, being told to express an idea again in English, being separated from our classmates who speak the same home language, and being sent outside of class.

The purpose of this first question is to have us pause and take stock of our actions. It’s simply a call to describe what we are doing and the actions that result.

However, it’s the crucial first step because when we do not pause to consider the impact of policy enforcement, we may never realize we may be contributing to potentially oppressive systems. In the example above, we stopped to notice all the other micro-aggressions associated with English-only policies.

2. Why am I doing that?

We now examine our actions through this second question. We ask ourselves: Why are we enforcing an English-only policy? The possible answers might be that

- We want to provide students with more opportunities to practice in the target language.

- We want English-only students to be included in the conversation among multilinguals.

- We want to make sure multilingual students are on task.

This second question identified our intentions and motivations. Only when we can clearly see our motivations can we critically examine them through an inclusive, anti-racist lens because the goal of anti-racism is to actively dismantle systems of oppression.

Plenty of harmful policies in a variety of contexts have had good motivations and well-meaning people behind them. But we cannot dismantle oppressive systems unless we first see the beliefs that fuel those engines and how they might harm others.

A good motivation does not always translate to equitable policies. That’s why we need Question #3.

3. How do my actions affect others?

Let’s examine how the motivations behind English-only policies may impact language learners.

► More opportunities to practice English

This motivation negatively impacts some language learners, especially beginners, because they will not be able to participate in class even though they are highly literate in their home languages.

The subversive message that this policy sends is that only one language is welcomed in class. If students want to participate, the entry ticket is to abandon their home language for mastery in English. It communicates that English is superior by designating English as the language for school involvement, implying that other languages are inferior and have no place or value in schools.

► Ensuring that English-only students are included in the conversation

The insistence that we include English-only students in every conversation comes at the expense of multilingual students. The impact is that some students may internalize that English-speaking students are more valuable than other students as they must be included even if it means other students (especially vulnerable beginning learners) are silenced.

► Making sure everyone is on task

This motivation explicitly communicates that the monolingual teacher does not trust students enough to speak/stay on topic in their home language. Again, this results in teachers policing students rather than supporting their interaction, and the students that must be policed are the indigenous and minority students. Instead of policing students, create activities that will make them want to engage in the activity so there will be less off-task behaviors.

► Separating students from their home-language groups

When students are separated from their cultural peers (as they often are), they internalize that they cannot be together if they use their home language. If this happens, then through lack of use, the policy will slowly erode their heritage language skills, which have been shown to increase literacy development in both languages and overall academic achievement (Cummins, 2014).

If students who speak the same language other than English are not regularly together, they may also start to lose a safety net – being around people who share similar values and practices – which may make school feel like an unsafe place. Furthermore, conversation is a known language tool to support students to understand content. Speaking in their home language, then, should be an academic strategy to foster comprehension (Zwiers & Crawford, 2011; Honigsfeld, 2019).

► Taking away points

When students lose participation points, they receive lower grades, which might impact them when they are applying to colleges. In addition, artificially lowered grades might cause them to be tracked into less rigorous classes, which further widens the opportunity and achievement gaps.

I did not go into all of the ways that English-only policies harm multilingual learners, but you can see even from this list that there are detrimental things we do to students in the name of a well-intentioned but misinformed policy that is, upon reflection, racist in nature if not intent.

Questioning all our policies and practices

Our education system can be problematic for many reasons, including

- punishing and policing instead of providing responsive services

- segregating instead of including everyone, and

- privileging one culture over others.

Because we are part of this system, we have to intentionally reflect on our practices and policies using this anti-racist framework. If we do not, we may find ourselves supporting an education system that – whether intentionally or not – is devaluing and segregating our students and erasing their cultures.

I hope that, using María’s framework, we will continue to question our practices and policies and have uncomfortable, brave conversations with our colleagues. Through our sustained conversations, we can gain allies in the anti-racist movement and better work together to dismantle any parts of a system that oppress others more than serve them.

References

Cummins, J. (2014, November 14). Reversing Underachievement among Immigration-Background Students: what does the research say? Politeknik. http://politeknik.de/reversing-underachievement-among-immigrant-background-students-what-does-the-research-say-jim-cummins-the-university-of-toronto-2/

Honigsfeld, A. (2019). Growing language & literacy: Strategies for English learners: Grades K-8. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Zwiers, J., & Crawford, M. (2011). Academic Conversations: Classroom Talk that Fosters Critical Thinking and Content Understandings. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.