Teaching U.S. History in a Fractured America

Editor’s note: Lauren and Sarah are long-time contributors to our MiddleWeb blog Future of History. They both teach 8th grade U.S. History – Lauren in Chicago and Sarah near Los Angeles.

Editor’s note: Lauren and Sarah are long-time contributors to our MiddleWeb blog Future of History. They both teach 8th grade U.S. History – Lauren in Chicago and Sarah near Los Angeles.

Their suggested title for this dialogue series: “Two white female teachers talking about teaching U.S. history in turbulent times.” See their bios at the end of the post. This is the third and final episode in a three-part conversation. Comments welcomed!

By Lauren Brown and Sarah Cooper

Lauren. We are getting closer and closer to the election, and I think anyone who teaches U.S. history right now is nervous about that. Things are so polarized that it is increasingly difficult to talk about basic civics without engendering controversy.

Sarah. We live in a time of twin pandemics – the coronavirus and racism. In the upcoming election, the two intersect and could at any time explode in our classrooms. In the fall of 2016, I tended to avoid national political discussion in favor of local issues, because the country felt so polarized, as you say. And now it feels immensely more so.

In discussing current events, it becomes clear that the virus’ impact on society is endless, not least in its disproportionate impact on communities of color. And now I’m already looking over my shoulder: Is simply writing or saying this statement a political act?

Lauren. That’s a great question. I, too, avoided discussing national politics in 2016. In hindsight, I feel like I chickened out. When students asked, “Who are you voting for, Ms. Brown?” I replied that it wouldn’t be appropriate for me to share my political views. But one of my Black students kept pressing me about it all year. And I came to realize that he felt racially threatened by the idea that I might have voted for Trump. He seemed to have a need to make sure I was “okay” in his eyes. Eventually, later in the school year, I did tell him that I did not vote for Trump.

And since Charlottesville, and given other things the President has said and done that I felt were blatantly racist (referring to Covid19 as the “Chinese flu,” or referring to some countries as [bleep] countries), I have come out publicly to my students that I cannot condone those views.

Trump has made it hard for me to be neutral, because being neutral feels like I am tolerant of bigotry. But I still feel the need to be careful about subjecting my students to my views. How can we avoid that?

Sarah. One approach is to have students be the ones to lead discussions of current events, which we do one day each week in my classes. They present an article, giving any opinions at the end, and then moderate a discussion where others comment.

In a majority liberal but not at all politically monolithic school, I’ve often had to caution students not to snicker or catcall when commenting on certain policies or actions, because I too want these middle schoolers to be respectful. But when do we step in to say that something is definitively not right, according to our school’s honor code or to another set of values?

Lauren. I love the idea of letting students be the ones to lead it. But yes, we do need to step in at times. After this year’s State of the Union address, my students were cheering about Nancy Pelosi ripping up the copy of Trump’s speech. I told them that we should be careful about condoning that behavior.

Imagine the opposite, I suggested. Imagine the Republican Speaker of the House ripping up Obama’s State of the Union speech. I thought it was important to give them another perspective. I wonder about how I might get students to consider other perspectives this fall?

Sarah. One tactic I’m hoping to use is to invite speakers via Zoom to my classes this year to present a literally and figuratively distanced perspective. Organizations such as the Pulitzer Center, which I learned about one year in the exhibit space at the National Council for the Social Studies’ annual conference, will connect teachers with reporters to talk about a variety of national and international topics. This also could be the year to connect with local columnists, activists and candidates who want to get their messages out.

Lauren. What a great idea! I am on that!

Sarah. As for providing other perspectives, I try to vary the sources of articles that I bring in daily so that we’re not just using our local Los Angeles Times but also the Wall Street Journal (for a more conservative view) – and not just for editorials but for news headlines.

Lauren. Bringing in different perspectives makes a lot of sense here. We all probably need to do more with teaching students how to analyze bias in news stories and understand the differences between editorials, opinion pieces and purportedly unbiased news.

I’ve also toyed with the idea of doing some kind of Skype thing with a class elsewhere in the country where students have very different views, but I’m not sure how well it would work. I used excerpts from this video by Middle Ground, which is a discussion between Trump supporters and immigrants.

The reactions I get from students are INTENSE. Many of them are quite vocal against the woman who wears the MAGA shirt. I like using the video, but it is not easy to use it well. It feels like I’ve simply provided an opportunity to fuel the majority’s anti-Trump supporter feelings.

Sarah. Returning to your point about teaching students to be respectful while hearing other perspectives, I’ll go back to Teaching Tolerance, this time with its Social Justice Standards. Under the four categories of Identity, Diversity, Justice and Action, points include:

Identity: “Students will express pride, confidence and healthy self-esteem without denying the value and dignity of other people.”

Diversity: “Students will express comfort with people who are both similar to and different from them and engage respectfully with all people,”

Action: “Students will speak up with courage and respect when they or someone else has been hurt or wronged by bias.”

Perhaps pointing to outside benchmarks such as these, whether we’re talking about President Trump’s tweets or Bari Weiss’ resignation letter from the New York Times, can help us encourage students to listen with an open mind.

Speaking of an open mind, how do you moderate, hide or otherwise address your own political views as a teacher when it comes to civics and activism?

Lauren. My own political views? That’s a tough question. I’ll answer an easier one. I have no problem and will find any opportunity I can find to remind them of the importance of voting and standing up for one’s views.

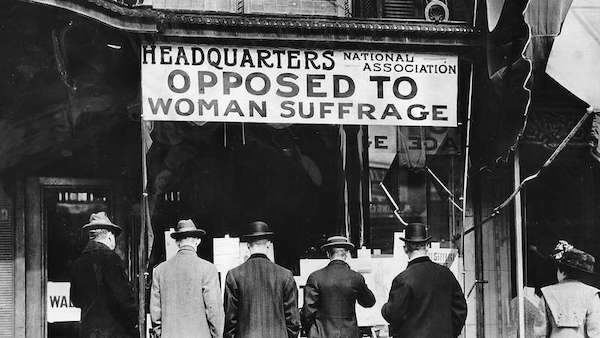

Teaching about women’s suffrage and the fight to get it, the risks and challenges that people of the past took to secure civil rights or speak out against racism, reminders about what happens when people don’t speak out (the Holocaust is a quintessential example) – all of these are good opportunities to remind students of the responsibilities of citizenship.

But I am evading your harder question.

Sarah. This is a hard question. In other words, what I guess I’m wondering is where you stand on history teachers sharing their own views with students or remaining as “neutral” as possible.

Lauren. I will evade this challenging question by asking another question: how neutral are we, really? When we choose what we put in the curriculum, we are not necessarily being neutral. History teachers always face the problem of what to cover, and when we decide what we are skipping, we are making choices. We are presenting a narrative.

I end up gravitating to social justice issues over, say, presidential elections, because that is where my heart lies and it’s a topic that resonates more with students. I can’t teach everything that happened during the Progressive Era, so if I have to cut, I’m going to cut the election of 1912 in favor of women’s suffrage.

But maybe the answer to your hard question is that we can turn it into a question of justice and decency. So it’s not about Democrats vs. Republicans, it’s about how we treat fellow human beings.

Sarah. This is a helpful guideline to determine when we share more of ourselves. Once in a while I let my own views come through, especially on topics such as infringements upon free speech, interruptions of Constitutional expectations or due process, or controversial actions that appear to violate our school’s honor code.

But mostly, especially with middle school, I try to address both sides of an issue – when there appear to be two sides. Or I simply avoid a topic entirely. That’s what I did with President Trump’s impeachment last fall.

Sarah in her U.S. History classroom.

The only times I introduced the proceedings were at the beginning and end, so that students knew what was going on. If we even began to discuss the issues, the red and blue lines in my classroom emerged so powerfully they were practically painted on the carpet.

Lauren. That never feels good as a teacher. The impeachment was a challenge. I just gave “status” reports – this is what is happening today – and explained procedural elements. I wanted to avoid partisanship and controversy, too. And yet, isn’t our job to be helping students learn to grapple with controversial issues?

Sarah. Yes, and sometimes this “nonpartisan” stance feels like a cop-out. Aren’t we teaching history to emphasize the importance of ethical understanding? Why am I here if I’m not helping students sharpen their moral critical thinking skills? We’ve talked so much in these dialogues about Teaching Tolerance and Facing History, and I believe in their approach to teaching tough topics.

Lauren. I’m grateful for their guidance, which is also helpful if one does get into conflict with parents or the administration. Thankfully, I haven’t. But it is heartening when teachers have the support of reputable organizations that have offered thoughtful ways of handing difficult topics.

Sarah. Four years ago, when considering this issue, I wrote guidelines for myself that I’ll try to dust off again this year:

- Pick topics with substantial middle ground where people can meet, think and compromise.

- Acknowledge that different views will exist, and we want to hear all of them.

- Pair a relatively light news topic with a heavier historical topic. It’s often easier to moderate our passions when we are discussing something in the past.

Lauren. Sarah, those are such fantastic guidelines to keep in mind. I will add two more.

- First, remember that sometimes it’s more about the questions than the answers. I’d like students to leave my class – on a daily basis and at the end of the year – feeling that I made students think and question. So it is okay to not have answers.

- And second: take deep breaths.

Sarah. Lauren, amen to that! I have so appreciated these honest conversations with you and feel energized to apply our ideas in class this year.

Lauren. Me too. Best of luck! It’s going to be a bumpy ride for everyone this year.

Sarah J. Cooper (@sarahjcooper01) teaches eighth-grade U.S. history and is assistant head for academic life at Flintridge Preparatory School in La Canada, California, where she has also taught English Language Arts. Sarah is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009) and Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom (Routledge, 2017). She presents at conferences and writes for a variety of educational sites. You can find all of Sarah’s writing at sarahjcooper.com.

Lauren S. Brown (@USHistoryIdeas) has taught U.S. history, sociology and world geography in public middle and high schools in the Midwest. She currently teaches 8th grade U.S. history in a suburban Chicago school district. Lauren has also supervised pre-service social studies teachers and taught social studies methods courses. Her degrees include an M.A. in History from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her blog U.S. History Ideas for Teachers is insightful and packed with resources.

ALSO SEE THIS WELL-DONE STORY:

Amid a Racial Reckoning, Teachers Are Reconsidering How History Is Taught (Daniella Silva, NBC News, 8/8/20)

Facing History has updated some of their resources. Check out their newly updated page on teaching current events.

Also, Facing History has updated their guidelines about fostering civil discourse. Read their recent blogpost about why and how they were updated: https://facingtoday.facinghistory.org/how-do-we-talk-about-issues-that-matter?utm_campaign=Back%20to%20School%202020&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=94157718&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-9ck0VMF787aXC3t_ynoBgA0w-wZBdUdPyeBPAj-LcFu9kUxTLi-SmxPWdSUL-toGXfrA0c1KhArMrKS2jSXPbui-ie2Q&utm_content=94157718&utm_source=hs_email

https://www.facinghistory.org/educator-resources/current-events/back-school-current-events?utm_campaign=Back%20to%20School%202020&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=94157718&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-_1yUfdXMKF3IPzn5JnUg9pKUmzUshRaVQXe5-c6Wd6fwwMOrgLxZYhkZU9FCUkAeM3_pevmsJ4mTehibaoyEDDFcKJiw&utm_content=94157718&utm_source=hs_email