Turning Enduring Issues into Ethical Debates

Is it really possible to get middle school students to talk respectfully to one another, especially if they don’t agree?

Catherine Steiner-Adair, a clinical psychologist and author of The Big Disconnect, notes that “Part of healthy self-esteem is knowing how to say what you think and feel even when you’re in disagreement with other people or it feels emotionally risky.” It’s a lesson everyone could benefit from, but especially valuable for middle schoolers.

Grappling with moral dilemmas and experiencing the process through which we arrive at collective agreement is essential in developing good interpersonal skills. More important, perhaps, is the process that arises when students learn how to respectfully “agree to disagree.”

In a social media driven world becoming increasingly more dominated by digital devices, it is imperative that teachers help students find their real voices.

I was fortunate to loop with one group of eighth graders for two consecutive school years. In that time, I engaged them in eight successful debates. We began in seventh grade with The Lost Civilizations Debate, where they examined the social morality of the first civilized societies by determining whether they were “Terrible people who did great things…or Great people who did terrible things.”

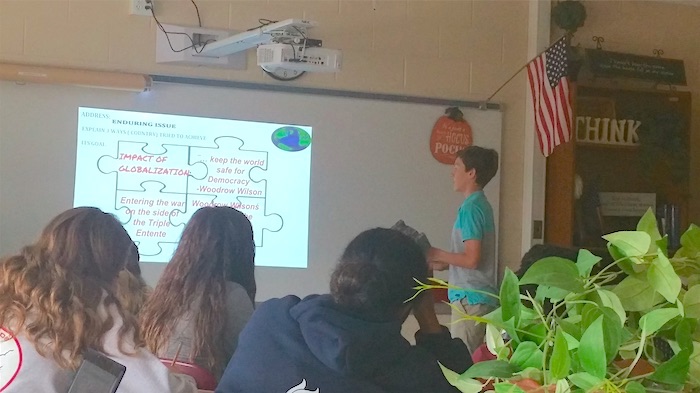

By the end of eight grade, we graduated to a series of more complex Impact of Globalization debates. Student groups now role-played the complex relationships that existed between the seven main nations that participated in both world wars. Our compelling question: “Was your country’s involvement in the world wars motivated more by POWER or MORALITY?”

As a result students become more familiar with how to address a compelling or open ended question from the point of view of their designated country. This familiarity leads to informed, well-rounded discussions on the long-lasting impact and issues that have affected people (and their relationships) over time. Hence, Enduring Issues.

Structuring the Project

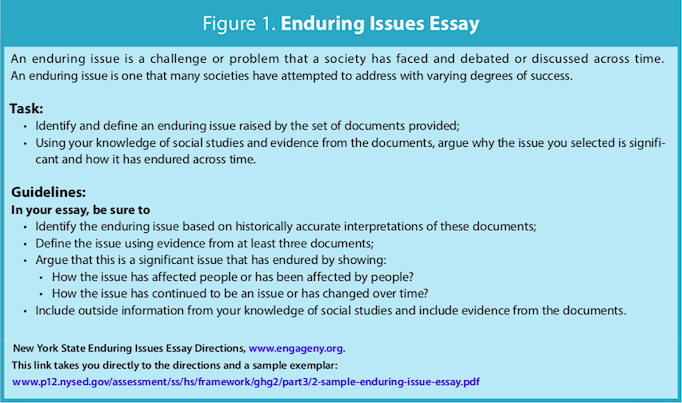

The key to each debate’s success was in the structure of the project, especially the scripting of how members of the class would interact with one another. Student researchers in each of the seven nation groups used both primary and secondary sources to cite the evidence for their respective arguments and were asked to write a joint Enduring Issues Essay based on the following guidelines:

Each student became responsible for researching, preparing and presenting one part of their nation group’s essay. Then, working collectively, students in each nation group plugged their essay into a Google Slide presentation template – reformatting their essay content into a debate presentation.

For example, student groups began with researching the role their assigned countries played in the outbreak of each World War – determining if their country’s involvement was motivated more by power or morality. After determining that answer, there was increased confidence with more complex questions, like “How do competing views of power and morality lead to global conflict?”

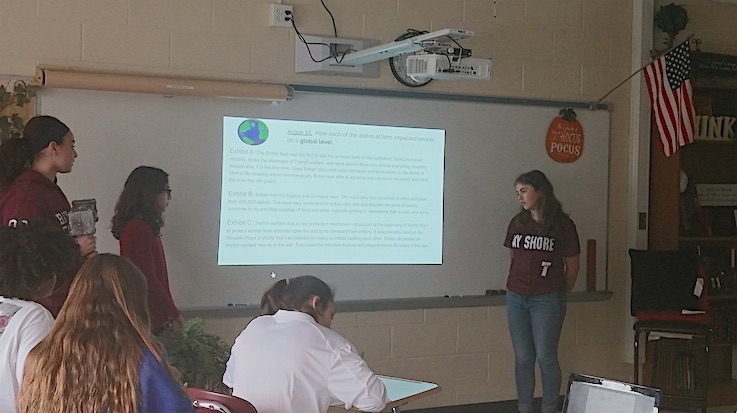

Student presenters engaging in debate on how the action of their country during World War 2 impacted people on a global level.

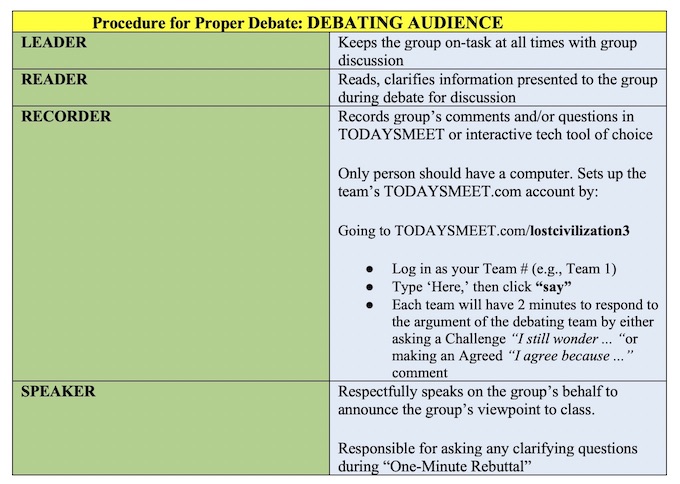

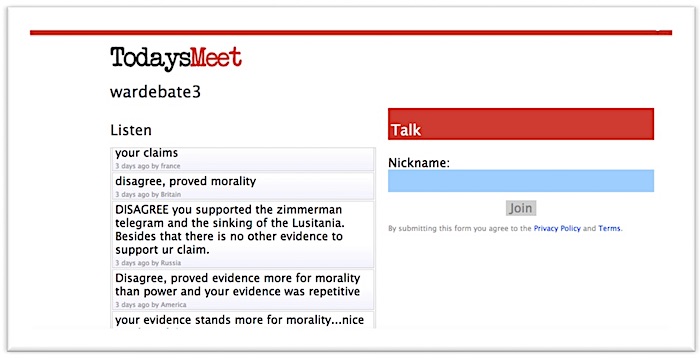

Since many students were initially intimidated when asked to speak their minds during presentations, we used the tech tool TODAYSMEET.com, where student responses could be part of our classroom dialogue in real time.

Socratic seminar type tech tools are genius for allowing us to reach every learner. Over the course of our first year, I watched so many students acquire a quiet confidence after being given repeated opportunities to use their voices. This was the motivation those quiet students needed to start speaking more intentionally and confidently.

Student group responses were recorded into TodaysMeet.com, a socratic seminar tech tool for discussion, reflection and debate in real time.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Todays Meet closed in 2018. Some educators are now using Socrative for purposes like this. (April, 2024).

The Debate Procedures

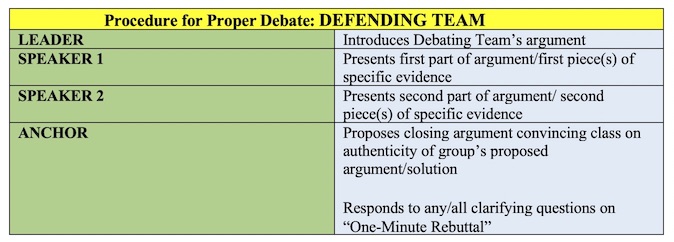

In each of our eight debates, students debated for three to four days, using the following procedures:

Procedure for Proper Debate: the Presenting Team

- All three to four student team members will be allowed to present, support and defend their team’s position to the class.

- Class will be responsible for taking notes on the compelling evidence presented by each group.

- After evidence presentation (see sample slides) is complete, fellow student groups will be allowed to challenge any part of the presenting team’s argument by respectfully submitting “I still wonder …” questions or statements.

- Debate team Anchors will have one minute to further respond to as many questions/challenges as possible.

Procedure for Proper Debate: the Student Debating Audience

Upon entering, the class collects their individual evidence packets provided by the teacher from the front of the room

Again, all students are responsible for taking notes on every team’s compelling argument in the teacher provided evidence packets.

When it is your turn to speak, the mallet is passed to you. Only the person holding the mallet may speak at any given time. Setting boundaries for debate creates that safe space necessary to allow all students to take risks, to feel heard and to allow for validation of their viewpoints.

My Takeaways

Watching my students enthusiastically approach and take personal interest in solving real world problems with moral and ethical twists were proud moments. The debate philosophy allowed those who were better verbal learners the opportunity to speak and express themselves. This in turn helped them to become better essay writers.

On the flip side, this two-stage approach allowed those who were better writers to learn how to be stronger speakers. It also gave the weaker test takers an opportunity to be verbal geniuses in debate. And, my struggling learners had the opportunity to create a unique bond with not just curriculum, but more importantly, their classmates. The results were learners who emerged viewing themselves as a little smarter and a lot more resourceful.

Although there were moments where some of students became rather passionate or engaged in ruthless pursuit to disprove their classmates’ positions, one of things that I admired most was the general level of respect that was maintained throughout the entire process.

Here are some comments from my students about their two years of debating experience:

- “We were able to express our opinions safely, without fear of being picked on.”

- “I liked seeing all the responses coming up on the board and having the chance to continue to talk about them the second time.”

- “Not only did you teach us about social studies, but you taught us life lessons that I will never forget.”

- “We have become more well-rounded speakers, writers, students and people overall.”

- “We learned a lot and also had a lot of fun.”

- “Even though they can be scary in the beginning, I would rather do a debate than have a test.”

- “Debates help struggling writers, like me, because we get to talk more about the issues with our classmates. Listening to each other helps us all better understand.”

Familiarity with curriculum and respectful peer relationships are key foundations of every student’s success. The next generation needs to be more civic-minded and needs to be better equipped to engage with complex moral and ethical issues while maintaining an academically sound work ethic.

Social studies class lends itself beautifully to providing opportunities for all students to speak intentionally with teachable moments of tolerance, respect, understanding and admiration for others’ perspectives and worldviews.

Jennifer Ingold (@msjingold) was chosen both the NCSS and NYSCSS Middle School Teacher of the Year in 2019 and has received the Cohen-Jordan Secondary Social Studies Teacher of the Year Award from the Middle States Council for the Social Studies. In 2022 she received the Mary K. Bonsteel Tachau Teacher of the Year Award from the Organization of American Historians.

She currently teaches eighth grade social studies at Bay Shore Middle School in Bay Shore, New York. She has been a speaker at local, state, regional and national conferences and has had her work featured in major publications such as Social Education, Middle Level Learning, and AMLE Magazine. See more of Jennifer’s MiddleWeb articles here.