Use Print and TV Ads as Informational Texts

“Have you been injured recently in an accident? You might be entitled to thousands of dollars in compensation. Call me Joe Lawyer at 800-555-5555.”

“Have you been injured recently in an accident? You might be entitled to thousands of dollars in compensation. Call me Joe Lawyer at 800-555-5555.”

“Does your house have problems with mold? If so, it could be harmful to your family’s health. Don’t ignore it. Let Rid-a-Mold give you a free estimate today.”

“Do your children get enough Vitamin C? Most don’t. That’s why they should get a daily dose of orange juice from our new Yellow Juice Pumpers available now at your local grocer.”

These fictitious pitches might sound familiar. Every day we are bombarded by advertising and marketing messages designed to get our attention and motivate us to buy.

For many years, I have been engaging teachers and students in a deeper understanding of advertising. Prior to the introduction of Common Core teaching standards, many educators taught ads as “techniques of persuasion.” Many have now migrated to teaching advertising as argument.

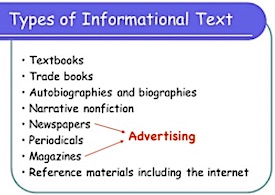

In this post, I’ll argue that ads are also “informational texts,” while acknowledging that many of you may not think of them, or teach them, in this way.

What are informational texts?

Advertisements do the same thing. Ads are part of what we think of as media, and media are texts.

In a print ad for pizza, discussed in my previous post Close Reading Advertisements, students can glean both the slogan and the name of the product simply by reading the text. (They can also analyze the images that contribute to the message.) By considering what’s missing, students can conduct research to determine the ingredients in the product.

Task your students with investigating the informational text features, for example, in a car advertisement.

This New York Times news article, which references the Nissan ad from 2010, reveals that GE invented the word “ecomagination” in its marketing—a combination of ecology plus imagination.

When analyzing media messages, students should brainstorm important questions. For example: What does the ad tell us about the car? What makes it different from conventional automobiles? What makes the car attractive? How does it speak to those concerned about the environment? What does the small print reveal?

As a media educator, I would also want students to consider:

- who created the ad (author) and why?

- what is the purpose of the ad?

- who is the ad trying to reach (audience)?

- what techniques does the ad use to get attention? (the color blue, for example, is significant. This website explains why)

- what important information is omitted (and why)?

Commercials as information texts

Video commercials are a sure way to get your student’s attention. They’ve been exposed to tens of thousands even though they may like to skip over them or ignore them. However, like print ads, they are perfect vehicles for teaching informational texts.

Like print ads, they provide students with information about a product, a service or a candidate. But in this 21st century world, they need to watch more critically: they must become active viewers and listeners in order to acquire important information.

In my workshops, I am always playing back commercials more than once, because mostly they go by so fast. (Think of it as re-reading a passage in order to dig deeper and discover information missed on the initial read.)

Now consider this one-minute 2010 Nissan commercial, part of its campaign to introduce the alternative-to-gas powered vehicles.

“What if everything ran on gas?” is the central theme of the ad. The commercial uses humor – imagining a world where everything we do (brushing our teeth, talking on the phone, going to the dentist) is gasoline powered. At first unsuspecting students might think this (gas powered products) was the way things used to be. To the people in the ad, using these gas-powered products seems natural, but of course it’s not.

The spot ends with the words “Innovation for the planet, innovation for all.” (Interestingly, the ad doesn’t offer specific facts about why electric is better than gas for the environment. Might we assume that among people who might buy such car, that is taken for granted?)

If students searched the web for the phrase “Innovation for the planet, innovation for all,” the result would be a number of articles which reference that phrase. Can they locate any that are critical of the product or that phrase?

Ad slogans such as the one Nissan used are designed to make the consumer feel good—if I buy this car, I’ll be helping the environment. [Ask students if this is an example of the TRANSFER persuasion technique.]

Did your students consider what the ad omits: how much the car costs; how long does it take to charge the car batteries; how far can I drive when it is charged; where is the next charging station? These were important considerations in the early days of electric cars.

Campaign ads as information text

As I write this, the airwaves are filled with commercials for political candidates hoping to get elected or re-elected. [If you’re seeking an online database of political ads, you might start here: Google’s Transparency Report.]

About 50 percent of the ads that air in federal campaigns are purely negative, but a number of them are also what we call contrast ads, which pit the policy messages of either candidate against each other. And if you combine those together, you get a huge majority of ads which do contain an attack on the opposition.” (Political scientist Michael Franz talking with NPR’s Scott Simon in October 2018.)

Political spots are perfect teachable moment opportunities. In July I wrote Media Literacy: Teaching Kids About Political Ads to provide timely advice on how to use these in the classroom.

Every political ad conveys certain information about an issue, the candidate or their opponent. Students should be skeptical of what is said in ads, and part of their “media literacy” education should be to question, research and verify claims.

Have your students be on the lookout for fact-check “ad watch” columns or TV news segments in which qualified investigative journalists reveal what is true and what is not in various claims. Here is an example from the Annenberg Institute’s well-regarded fact checker service:

Annenberg’s FactCheck is non-partisan – you can also find reports on Biden’s misrepresentations, for example.

Ads can boost student engagement

Now is a good time to think about how to engage your students with ads and commercials that connect directly to your teaching standards.

With a little practice, you’ll be comfortable helping your students become better “critical viewers” as they read and watch.

“I’m Frank Baker and I approve this message.”

Recommended Resources

Analyzing Visual Texts

Good tutorial on deconstructing ads

Five Types of Informational Text Structures

The vast majority of texts are written to make an argument, to inform, or to tell a story.

Political Ad Analysis Worksheet

A tool your students can use as they examine campaign ads.

Best Fact Checking Websites for Students

Common Sense Media specializes in rating resources for kids and teens.

CNN’s Facts First

Focused on political claims and advertising – nonpartisan and very busy during elections!

Teaching Inference With Commercials

Scroll down to see ideas and a free infographic.

Deconstructing a TV Commercial (lesson plan)

This activity based on a 2009 mobile phone ad may seem quaint, but the commercial’s ability to engender fear and anxiety in 60 seconds makes it a classic.

Pictures and Slogans Persuade an Audience

A flexible grades 6-8 lesson plan from Scholastic that includes ad analysis.

Persuasive Techniques in Advertising (ReadWriteThink)

Originally aimed at grades 9-12, this lesson from the venerable NCTE-supported site has ideas adaptable to middle school, including a download that offers a list of colorful names for techniques like: weasel words, magic ingredients, plain folks and snob appeal.