Virtual Teaching Ideas: Fisher, Frey and Hattie

Last spring we experienced “emergency” teaching. Few of us had any time to prepare for distance learning before being thrown into the pandemonium sparked by the spread of Covid-19.

Last spring we experienced “emergency” teaching. Few of us had any time to prepare for distance learning before being thrown into the pandemonium sparked by the spread of Covid-19.

Now, with some hard-won crisis-level experience behind us, we have spent the summer regrouping and investing much-needed time in planning and preparing for the new school year.

We still have much to learn, of course, and a new book from three internationally known experts on teaching and learning can help – even if your school has already opened.

The Distance Learning Playbook – written by Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and John Hattie – made its timely appearance in July, rushed out in the hope that the insights of these three thought leaders and their 70+ teacher collaborators from around the world can help us become more successful virtual educators.

This article summarizes my August podcast conversation with Doug Fisher – highlighting key concepts of the book that can help us write our own playbook for engagement and impact in any setting – virtual, blended and face-to-face.

How was this book written so quickly?

From collaborating with these 70 teachers, Fisher, Frey and Hattie were able to see a pattern emerge of what effective distance learning instruction looks like for students. They used Hattie’s meta-analysis study of high-impact teaching influences to cull their observations of these lessons. The book, intended for grades K-12, is the embodiment of what they observed – framed around effective teaching influences.

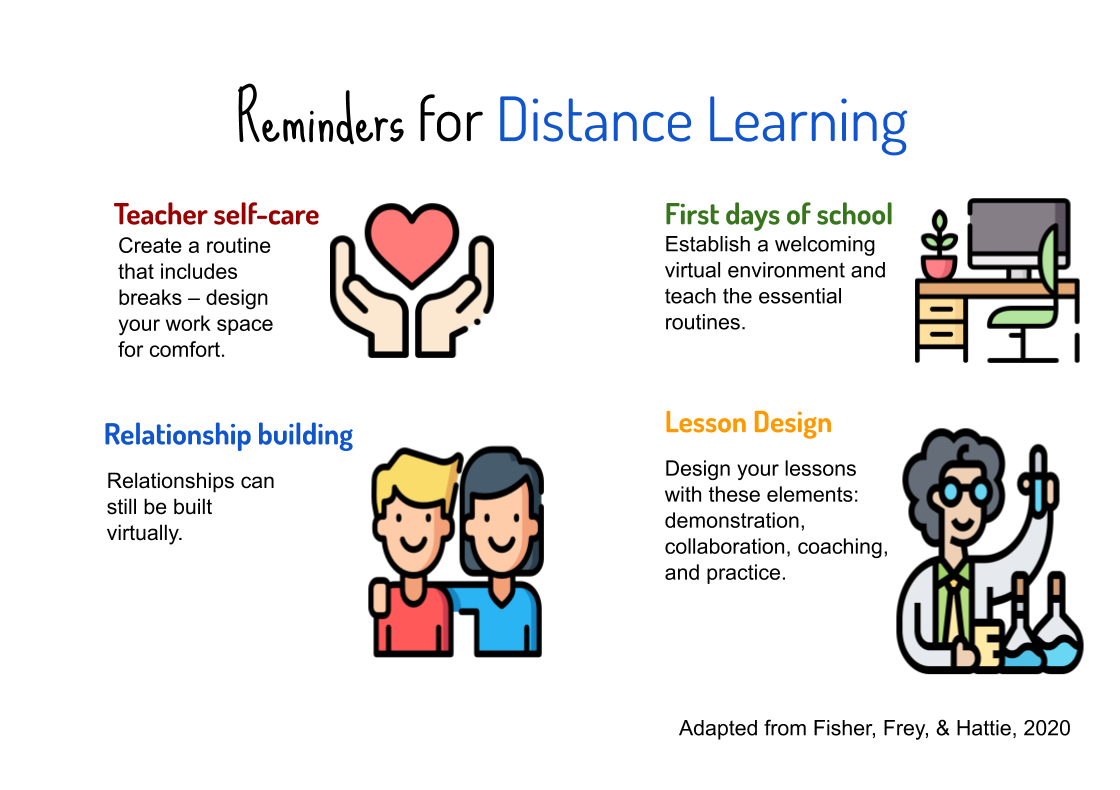

Teacher self-care

Working from home does not make teaching easier for teachers. There are many distractions and demands for a teacher’s attention while in their own home. Managing all of these factors and teaching online can leave teachers stressed and exhausted.

To combat this distance fatigue, the authors recommended:

- Creating a designated workspace

- Scheduling in breaks

- Establishing routines for the morning and afternoon

- Virtually connecting with people outside of your home

- Communicating guidelines with family members when working from home

(Two engaging modules associated with the book are available for free download, including Take Care of Yourself, a quick 15-page read that addresses self-care in some depth.)

First Days of School

As the book went to press, the authors predicted that the first days of school in 2020-21 would be different than the first days of emergency teaching. They’re being proved right as schools across the United States open now.

Just like the first days of in-person schooling, we need to create a welcoming space that makes students feel comfortable and to teach our essential routines.

To help students acclimate to the new virtual learning spaces, we need to:

- Explain or co-construct the class norms

- Demonstrate how to use our learning management system (e.g., Google Classroom, Seesaw, Powerschool, Managebac)

- Clarify what are respectful and appropriate behaviors during video conferences

- Describe how to access the frequently used platforms

- Walk through the daily and weekly schedule

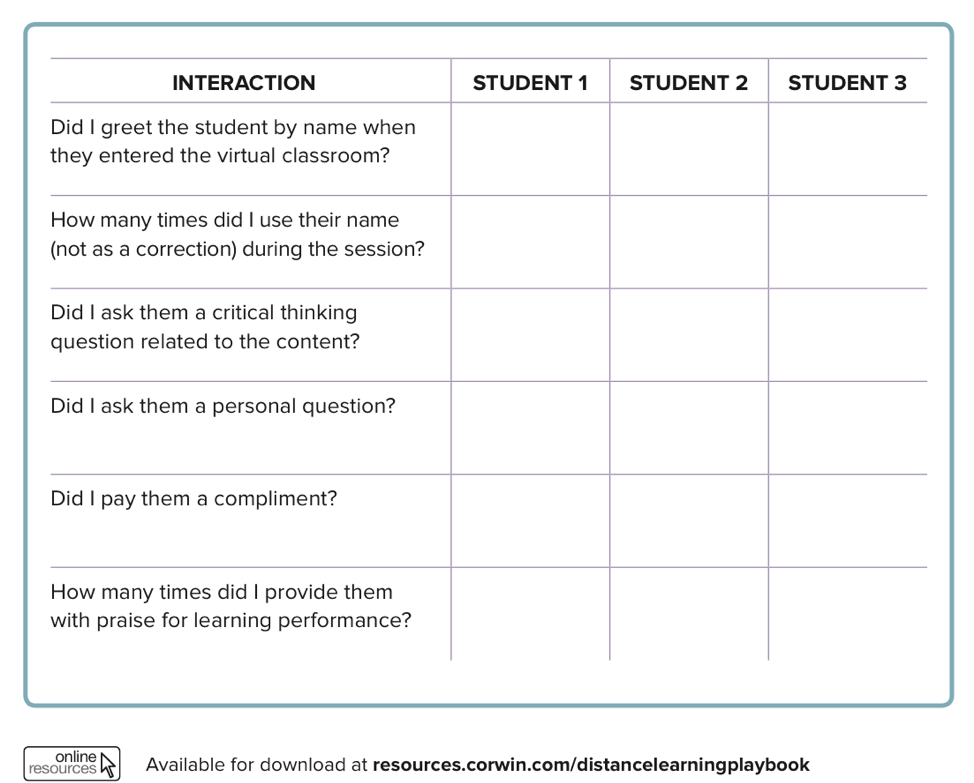

Relationship Building from a Distance

Relationship building must and can occur even while we’re physically distant from students parents and guardians.

While we had already formed in-person relationships with our students when schools started to shut down in the spring of 2020, most of us have new students this school year. Forming relationships with students is key to engaging them, whether in-person, in hybrid situations, or in long-term distance learning.

The characteristics of strong teacher-student relationships (Cornelius-White, 2007) include:

- Teacher empathy – How do students seek connections with you?

- Unconditional positive regard – How will your students know you care about them as people?

- Genuineness – How will your students know you care about yourself as a professional?

- Nondirectivity – How will your students know you hold their abilities in high regard?

- Encouragement of critical thinking – How will you foster critical thinking?

The authors recognize that there will also be some hard-to-reach students. They suggest we do the following things on this list to try to connect to them. However, I think this is a wonderful list for teachers to do in general with all students, not just those who are hard to reach (2020, p. 57).

As a teacher of language learners, I recommend one task in particular: make sure to have students teach you and their fellow classmates how they want their names pronounced. One idea is to create a Flipgrid discussion board with a few introduction questions (e.g., how to say your name, do you have a hobby, favorite thing you did this summer). Students could then be directed to record their introduction and respond to several classmates’ Flipgrid recordings.

This academic year, I’ll be running Dialogue Journals with my Advisory class. Each student will maintain a journal with me, and we’ll use it to establish and nurture a relationship on an individual level. Because my school is returning in-person, we’ll use physical journals, but you can also start digital ones using platforms, such as Google Docs.

Lesson design

The authors also concluded, “Ineffective approaches to learning are ineffective in digital spaces too” (Fisher, Frey, Hattie, 2020, p. 168). After observing and collaborating with more than 70 teachers, they noticed the same core elements of effective instruction emerging. They include:

- Demonstration

- Provide students examples of what they will do or learn using practices such as direct instruction, think-aloud, think-alongs, worked examples, lectures, and share sessions.

- Collaboration:

- Design experiences where students talk to each other about unit-specific topics through such practices as book clubs, text rendering, jigsaw, and reciprocal teaching.

- Coaching and facilitating:

- Conference with students to guide their understanding and thinking, and help them make meaningful connections.

- Practice:

- This does not imply “drill-and-kill.” Provide opportunities to apply, synthesize and/or create as a form of engagement with the topic and to develop skill mastery.

These four elements can be grouped into two categories: asynchronous and synchronous online learning. Asynchronous learning consists of demonstration through pre-recorded videos. If an activity does not involve live collaboration, practice can also be asynchronous. This leaves collaboration, coaching, and facilitating as elements of synchronous (live) learning.

I realize that students have varying degrees of access to technology and the internet, but if they do, try to incorporate synchronous learning experiences as much as possible. Learning, even in digital spaces, is a social experience (Vygotsky, 1980).

My Takeaway

Distance learning is uncharted territory for the majority of teachers, but a worldwide pandemic has forced it upon us all, at least in part. By following the advice in Fisher, Frey and Hattie’s new book, we can start to create a virtual environment that looks and feels a little more like the physical one we’re used to. It may not be identical, but it can be successful.

(NOTE: You can find several dozen free videos of collaborating teachers sharing tips – and all of The Distance Learning Playbook reproducibles – at this Corwin resources page. Corwin has just published a version of this book for parents.)

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143.

Hattie, J. (2018). 250 Influences on Student Achievement. Retrieved.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.