Student Choice Is More Than a Buzz Phrase

A MiddleWeb Blog

New MiddleWeb blogger Alex Valencic is an avid reader whose “to be read’ pile is more of a shelf stuffed with books. A former 4th grade teacher and now a district curriculum coordinator for 21st century teaching and learning, Alex is merging his love for reading with his love for education innovation to produce Reading for the 21st Century, a series of book-inspired reflections on effective classroom practices. Watch for new entries every six weeks or so. Here’s his first!

New MiddleWeb blogger Alex Valencic is an avid reader whose “to be read’ pile is more of a shelf stuffed with books. A former 4th grade teacher and now a district curriculum coordinator for 21st century teaching and learning, Alex is merging his love for reading with his love for education innovation to produce Reading for the 21st Century, a series of book-inspired reflections on effective classroom practices. Watch for new entries every six weeks or so. Here’s his first!

By Alex T. Valencic

Education jargon swirls about us every minute of every day as we are at work, much like the annoying flies and gnats that seemingly swarm around me every time I go camping or hiking.

I imagine this constant quiet noise of jargon is one reason why we often refer to them as “buzzwords.” However, there is some jargon that we use in education that cannot and should not be simply buzzwords.

One of those terms is “student voice,” which is often paired with “choice.” Just looking around my desk, I count no fewer than ten different documents, posters, cards, and books that have this term on them somewhere. But what do we really mean when we say that “student voice and choice” are an integral part of our modern education system?

It’s not just for special occasions

The Buck Institute for Education, which developed the Gold Standard PBL model for project-based learning, defines student voice and choice this way: “Students make some decisions about the project, including how they work and what they create, and express their own ideas in their own voice.”

In giving students choice, we empower them to take charge of their learning. By encouraging them to express their learning in ways that make sense to them, we demonstrate that what they say and how they say it matters.

As the Curriculum Coordinator for 21st Century Teaching and Learning in my school district, I have the responsibility to support modern pedagogical practices across all content areas. That means, among other things, that student voice and choice cannot simply be a practice for the “inquiry” classes such as science and social studies, nor can it be reserved for “extra” activities.

No, we need to incorporate these practices into all instructional settings throughout the P-12 system and especially during the crucial middle years when students are no longer learning how to do but rather doing to learn.

Sparks across the curriculum

Students need the opportunity to make choices about what they are learning and how they are learning it. And no, this doesn’t mean education becomes a free-for-all in which students do whatever they want whenever they want. Rather, it is a call to action for educators to know their students and to help spark a love of learning that will last a lifetime.

If we are to take this responsibility seriously, we must first start with ourselves. Are we lifelong learners? Do we discuss our learning lives with our students? When I was in graduate school, I spoke with my students about my university classes. It didn’t matter if they understood the intricacies of education law, finance, and leadership; what mattered was that they knew I was still learning.

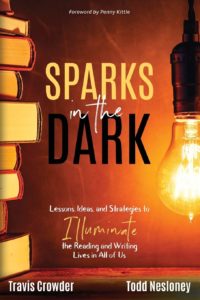

Before and after graduate school, I also modeled learning by sharing my reading choices with students. As we share our reading lives, we teach them that we know that learning is not only “messy, hard, and filled with mistakes and struggles,” but also a way that we experience “powerful moments that can’t be replicated anywhere else” (Sparks in the Dark, p. 55).

Students don’t go easy on themselves

Many educators who push back against the idea of allowing students to direct their learning experiences, especially when it comes to reading, argue that students will only read simple books and never grow. Those who have taken the leap, though, can attest that students push themselves much harder and faster when they are the ones making the decisions.

Why? Because when students select a task and succeed at it, it gives them a boost in confidence. They try something that is a little more challenging. Each success brings growth and encouragement to stretch themselves! Just as we ask our students to trust us to do what is best for them, we need to trust them to make the right decisions. (And on those occasions when they go astray, we guide them back onto the right track.)

Those times when you had a choice

As an educator, reflect on the learning experiences you had in your middle grade years that had a lasting impact. You probably are not remembering a math worksheet with 25 computation problems on it or a reading quiz you took after finishing a book your teacher assigned to you.

Chances are you are remembering the books you selected from the library, the messy projects you worked on with your friends over the weekend, or the giant diorama of the Civil War that your class made and updated as you learned about the conflict over ending slavery. It is time to give your students the same kind of experiences. Give them choice and let them use their voices.

All it takes is a single spark.