SEL & the Brain: Every Student Has a Story

By Marilee Sprenger

By Marilee Sprenger

Students enter our classrooms with their own personal stories. Some of those stories are wonderful. Some are not.

For those with positive stories, social-emotional learning helps reinforce the skills they need to succeed. For those with stories that include any degree of trauma or stress, SEL can help balance the negative experiences with positive ones.

Educational neuroscience leads us in a direction that takes us more swiftly into the integration of SEL in our classrooms. If you are willing to follow along while I highlight some key findings about how our brains learn, we can then consider six key SEL competencies that we can put to work as we teach and support all our students. [My glossary can help!]

Strategies that brains find stimulating

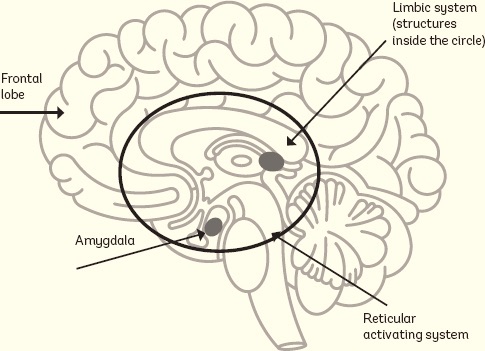

The research suggests certain brain areas and chemical compositions can be activated by the strategies we choose. For instance, building relationships with our students in person or online activates the trust/love system in the amygdala (the emotional center in the brain) rather than the stress response system. (Cantor, 2019)

From the emotional center, information flows easily to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and initiates the release of dopamine (the reward chemical) and oxytocin (often called the “cuddle” chemical). The prefrontal cortex is where learning, working memory, decision-making, and other executive functions reside.

Brain-based strategies have always been centered on the ability to get information to run smoothly from the brain stem to the limbic system to the PFC.

Relationships, relationships, relationships

Building relationships with your students is literally at the heart of teaching SEL. A study that was done in 2018 at the University of Minnesota found that positive greetings at the door increased academic engagement by 20%, and decreased disruptive behavior by 9% which added up to an hour more of engagement over a five hour school day!

Beyond greetings we can: write notes to students, share our own story with them, regularly use their names (pronounced correctly!), and use the 2 x 10 strategy in which you speak two minutes a day with the same student or the 5 x 5 strategy in which you spend five minutes a day for five days with a student. [Learn more in Chapter 1 of Marilee’s latest book.]

Relationships and empathy are the pillars of SEL. We model empathy and provide strategies to increase their empathy. This can include face to face conversations (when we are able) that are genuinely eye to eye. Empathy expert Dr. Michele Borba says eye contact is important. (How do you get seventh graders to look anyone in the eye? Staring contests!)

There is a brain structure called the right supramarginal gyrus (a mouthful!) that needs to allow our brain to “autocorrect” as it spontaneously thinks of itself first. This autocorrection develops over time and should be working quite well by middle school. To help it develop (and thus not always think of ourselves first), we can offer empathy-building experiences such as community service projects, volunteer work, and even caring for a classroom pet.

Five Key SEL Competencies

Self-awareness.

This is where teacher greetings might include questions like “How are you?” Checking in throughout the day helps students take a moment to examine how they are feeling. Colored sticky notes can represent an emotion, so students can grab one from your desk and stick it to theirs. You can visibly see how the class is feeling.

Emotion Word Walls are also useful in helping students describe how they are feeling. Dr. Marc Brackett (2019) tells us that labeling emotions helps others help us. (Are you mad or just mildly irritated? Scared or anxious?) Journaling is another strategy that helps students understand what they are feeling.

Keep in mind that self-awareness is the only way we can access the emotional brain on a conscious level. We can utilize the “ask, don’t tell” philosophy. Instead of telling students how they are feeling, ask them. For instance we often say, “You must be feeling sad right now.” What if the student is not feeling sad and begins to think something is wrong with them? Say, “How are you feeling right now?” If you don’t get a response, then you can share what you are feeling to encourage a response.

Self-management.

In the brain this is a dance between the emotional center and the thinking center. If students are in an environment with an adult they trust, self-control becomes easier. Stress interferes with self-management. Predictability is a must when dealing with stressed students and can be provided through the rituals, routines, structures, and procedures that are in place in the classroom.

Knowing what is going to happen next is absolutely necessary for those brains that spend most of their lives fearing the unknown. “Will Dad be lashing out with his fists or with his tongue?” “Will I be belittled or will I simply be ignored as though I don’t exist?” “When I get home from school, will Mom be sweet or screaming?”

Schedules, agendas, calendars, and other visual materials let students know what’s coming up. Learning does not take place when the brain is anxious; the brain can only try to survive. So we need “destressors.” Teaching students the “90 Second Rule” can be helpful.

Brain scientist Jill Bolte Taylor, author of My Stroke Of Insight, describes our ability to regulate a neurological process that she calls the 90-second rule: “When a person has a reaction to something in their environment, there’s a 90-second chemical process that happens; any remaining emotional response is just the person choosing to stay in that emotional loop.” (Psychology Today)

Based on this insight, we know a stressor need only last 90 seconds if we use that time wisely. I teach my students CBS, count, breathe, and squeeze (a stress ball, stuffed animal, etc.). That fills up the time and lowers stress.

Social Awareness.

This involves understanding others’ feelings and responding appropriately in social situations. Brain fact: The inferior parietal lobe encodes familiarity and social distance (how close you are to others). But the chemical dopamine is a major player in friendship along with oxytocin and serotonin (a calming chemical). We want the brain to release dopamine to help us out.

Movement and play can do this. When kids are playing together, they can bond (oxytocin released). Also, they are often on teams which makes them feel like they belong (serotonin). Many students also need to be taught how to read faces and body language (which together make up 93% of communication). Empathy must be practiced in social situations, so a refresher may be helpful.

Handling relationships.

Once students are aware of their feelings and can manage them, they can begin to deal with others’ feelings. Learning can be lonely. With remote learning, students can feel that they don’t have someone to bounce ideas off of or coach them through a problem.

It’s important that we help our students handle relationships in person and remotely. As they learn together in pairs or small groups, they are inspired with new ideas and different opinions. This is achievable through teaming and other cooperative learning strategies.

Project based learning is very successful as students work together toward a goal, and role playing is another excellent way to get students to interact with each other. As they take on another character or role, some students find it easier to talk to classmates.

Some schools use assigned seats at lunch and switch the seating pattern so students meet and speak with different schoolmates. Teachers often cruise the cafeteria and initiate conversations at less interactive tables.

Decision making.

The prefrontal cortex is dominant in decision-making. It is in this part of the brain that teachers make about 1500 decisions a day! (Goldberg & Houser, 2017) Students need to be made aware of the number of decisions they make, from choosing what to wear to who they speak to on the bus or playground. Dopamine is the reward one gets from making a good decision – it comes from the nucleus accumbens, which is part of the reward system and pleasure system in the brain.

You can offer students choices (e.g., when you have them pick classroom jobs), but first talk to them about their values and the priorities upon which we base our decisions. And don’t overload kids with too many choices. Be aware of decision fatigue for both you and your students. It appears to be more prevalent during the pandemic. (You get home and someone says, “Hey, what’s for dinner?” and you want to crawl into bed and not think. That’s decision fatigue.)

We have super-stressed brains right now

Whether our students recognize it or admit to it, their brains (and indeed our own brains) are stressed from a world-wide pandemic that has many feeling out of control and helpless.

In school, that leaves us with many brains that are dysregulated – that is, they are living in a fight or flight state. A dysregulated brain causes erratic thinking, heart rate, breathing and behavior.

Dysregulation is countered by coregulation. Social emotional learning teaches us that it takes a calm brain to calm another brain. For those students who are unaware of how to calm their brains, social emotional learning is key in both our remote and our in-person classrooms.

Managing our stories

Every student has a story, and every teacher has a responsibility to help rewrite or reinforce that story.

When Margaret jumps up off her chair and runs out of the room when the lights are dimmed for a video, or when Anika ruins her chances of making new friends in a new school because she doesn’t have prosocial skills, or when Angel runs into school late every day because Dad has left and he is now the man of the house and must make sure all of his siblings get to school first, who will they trust to help them?

Every student’s story is different, but they all have one thing in common – they need social emotional support to create a new version. We must keep in mind that it takes only one caring adult in a student’s life to change the trajectory of their story.

Borba, M. (2016). Unselfie: Why empathetic kids succeed in our all-about-me world. New York: Touchstone.

Brackett, M. (2019). Permission to feel. New York: Celadon Books.

Cantor, P. (2019, February 13). The school of the future: A conversation with Dr. Pamela Cantor [Presentation]. Turnaround for Children. Retrieved from https://www.turnaroundusa.org/school-of-the-future-gsvlabs/

Cook, C. R., Fiat, A., Larson, M., Daikos, C., Slemrod, T., Holland, E. A., Renshaw, T. (2018). Positive Greetings at the Door: Evaluation of a Low-Cost, High-Yield Proactive Classroom Management Strategy. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(3), 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717753831.

Goldberg, G., & Houser, R. (2017, July 19). Battling decision fatigue. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/ battling-decision-fatigue-gravity-goldberg-renee-houser

Marilee’s new book Social-Emotional Learning and the Brain: Strategies to Help Your Students Thrive is available in paper and e-format at the ASCD Bookstore. You can reach her through her website, e-mail brainlady@gmail.com, or on Twitter.