Need a Real World STEM Project? Try Plastics Pollution

A MiddleWeb Blog

The kids you teach have never lived in a world unpolluted by plastic trash.

The kids you teach have never lived in a world unpolluted by plastic trash.

And who would believe it now, but today’s plastic plague actually began as an attempt to protect the environment.

It started with elephants. In the late 1800s the demand for ivory to make billiard balls threatened the elephant population. An inventor, John Wesley Hyatt, rolled out the first form of plastic as a substitute for ivory and started a revolution.

For the first time manufacturing was not limited by nature – we could create new, inexpensive, durable materials to meet our wants and needs. Plastics could keep people from depleting the world of its natural resources, including wildlife. The future looked promising.

World War II accelerated the drive to find new plastics to replace scarce natural materials, and plastic production in the U.S. increased by 300%. Products such as nylon and Plexiglas burst onto the scene. Plastics were on a roll!

These materials are strong and durable, cheap to produce, and lightweight as compared to natural materials. In fact, replacing natural materials with plastics does conserve some natural resources.

The problem with plastics

But are plastics too much of a good thing? Today, plastics materials are literally everywhere! They are components of most merchandise in stores, commercial outlets, and any other facility you can name. They fill pantries, trashcans, and closets (yes, polyester clothing is a form of plastic). They litter yards, roadsides, drainage areas, landfills, watersheds, and oceans. Tiny microscopic pieces are even in the air.

And plastics don’t go away. They take centuries to break down. They are practically indestructible.

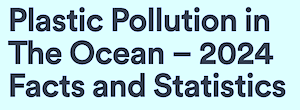

Consider this: From 1950 to 2017 the world created 6.3 billion tons of plastic waste and 91% of this has never been recycled. Just the plastic going into oceans will increase from 11 million tons to 29 million tons by 2040 at the rate we’re going now. By 2050, ocean plastic will outweigh the ocean’s fish.

To top it off, now we’ve discovered that plastic fragments break into increasingly smaller pieces (microplastics, and nanoplastics) which harm marine life, enter the food chain, get into the air, and threaten our health. In July 2022, the World Economic Forum noted that “microplastics, tiny particles less than 5mm in size, are everywhere – including in our bodies. In 2018, they were first detected in human feces. In March 2022, they were also found in human lungs and blood.”

And plastics contribute significantly to climate change. Surprised? Check it out.

Recycling plastic has a long, strange and erratic history, as reported most recently in stories from NPR and PBS’s Frontline. As this history reveals, the oil industry turned to recycling to beat back legislative initiatives to ban or curb the use of plastics, in full knowledge that recycling would never compete effectively with new plastic. In fact only 10% of plastic has been recyled since the 1970s when the industry claims began in earnest.

Plastic industries now pledge that their packaging will consist of 100% renewable, recycled materials. That sounds good, but currently 90% of items made from plastics are for one “single use,” after which we throw them away. This creates an ongoing demand for replacements. Since making items from new plastic costs just half as much as using recycled plastic, industry has little motive to follow through on its pledge. In fact, industry is engaged in a long-standing campaign for single-use plastics.

So What’s the STEM Connection?

So, here’s the deal: We need to solve this plastics problem. We can’t just look for solutions to plastic pollution that already exists in our environment. We must find ways to reduce and alleviate plastic contamination at the source – the production level.

I know STEM teachers are always looking for real-world challenges their STEM students can tackle. The challenge doesn’t get more real than this: What will we do about the problem of plastics pollution while continuing to produce and use plastics?

This complicated challenge highlights the value of STEM education – the most powerful way to cultivate a generation focused on healthier and safer societies is to engage them now in issues they will face as their lives progress.

Our kids need to ratchet up their plastics IQs and work together on sensible solutions. In doing that, they’ll be building lifelong problem-solving competencies and approaches they can use to tackle other issues that matter. Bring on the STEM!

Some current plastics kick-starters

To deal rationally with the problem of plastics kids need to start by expanding their plastics literacy and exploring a variety of “solutions” already in the mix. Just a few ideas. . .

Produce new plastic-eating enzymes. Scientists are working on a new technique for breaking down piles of plastics. They have created a super-enzyme that degrades plastic bottles six times faster and would make it possible to completely recycle single-use bottles. Researchers are also attempting to engineer this plastic eating phenomenon to break down and recycle clothing containing polyester. How can kids get involved?

Start community-based initiatives. In Ghana, women earn money from collecting and selling plastic scraps. While this may seem like a small effort, in just one year this initiative created eight jobs in the community and successfully kept 35 tons of plastic from becoming litter. Remind kids to keep small solutions in mind, as well as big solutions, when working with STEM projects.

Create recycled treasures from plastics. In arts classes kids can create a variety of art from discarded plastic items. Recycled treasures are an especially good project for “makers.” My community holds an annual student art show with a category featuring recycled art. Making Art with Plastic Waste shows some amazing large-scale art from recycled plastics.

Develop ways to extract microplastics from the environment. Kids are already helping to solve this problem. Check out Teen develops innovative method for extracting microplastic pollution from water. This STEM-minded teenager (who received a $50k first prize) found a way to use a magnetic liquid that sticks to the plastics and allows him to remove them from water using magnets. An international judging panel recognized this as an innovative, practical method to “start cleaning our oceans, one filter at a time.”

Produce better plastics. Products with packaging that claims to be “biodegradable” or “compostable” is a start, but these often degrade only under special conditions and can complicate recycling efforts. Producing fully biodegradable products would require 11% of the total land available on earth and compete with food crops. This area has promise but still needs serious problem-solving.

Recycle existing plastics. Recycling has been on the radar for decades, but the U.S. actually recycles only about 5-6 percent of its plastics. Kids may enjoy plunging into recycling and looking for solutions to make this once popular practice more workable as a community-wide project where each stage of the recycling process is monitored and understood by the public.

Plastics were invented for a noble and humane reason. Today, they are endangering our future. Let’s help look for ways to put plastics in a more favorable position in our world.

UPDATES:

Here are two (Sept 2021) background knowledge resources from Consumer Reports magazine: The Big Problem with Plastic and How to Quit Plastic: Ways to reduce this kind of waste—and its environmental impact—right now. Each story includes links to other CR info, including articles like “How to Eat Less Plastic.”

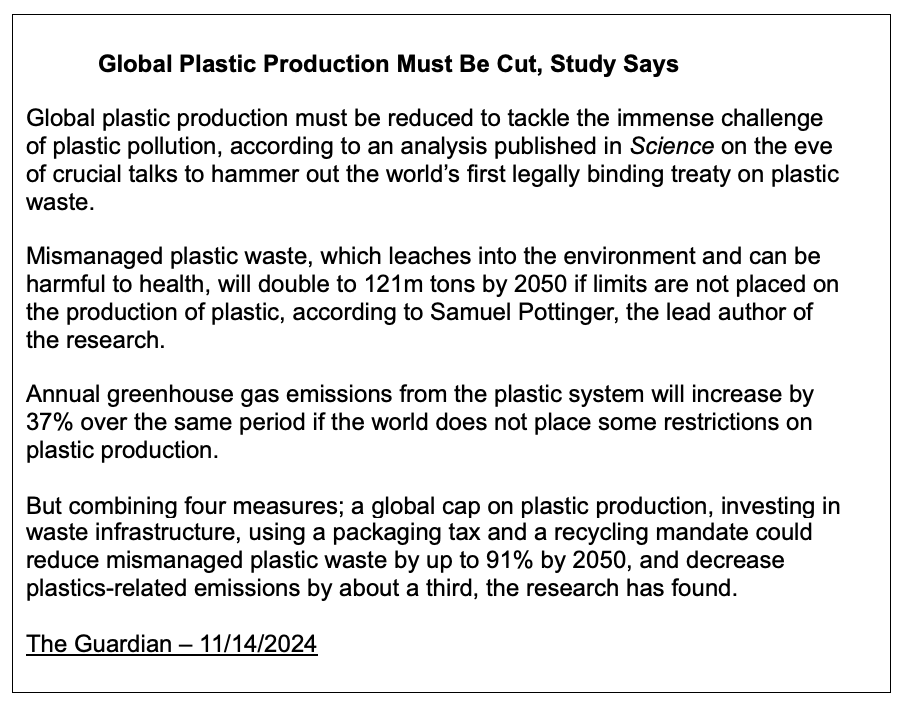

For regular, up-to-date reporting on the plastics pollution problem, see this curated page at The Guardian newspaper. (2024). Here’s an example from February 2025: “Levels of microplastics in human brains may be rapidly rising, study suggests.”

Could we just use biodegradable bamboo packaging?