Writing Workshop Ideas for the Middle Grades

Writing workshop can be an exciting part of the day for middle school students. The goal is to make sure that students are always writing.

If your schedule is not a good fit for a daily workshop format, creating opportunities for students to connect with literature and respond in writing is another way to grow successful writers.

Regardless of the schedule you create (or the one you must follow), the first months of the year are a great time for you to get to know your students as writers through a rich collection of their work.

To accomplish this task, you are not going to be able to grade everything. And that’s okay. Give your students some prompts that require short bursts of writing energy and let them build their pile. Read poems and encourage your students to borrow a line to begin a poem of their own – or use a poem set to write about a topic or idea.

Encourage your students to examine family photos, pictures from a file you’ve created from magazines, or borrow a scaffold to write an apology poem, such as “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams.

Writers learn to write by noticing what other writers do. Give students opportunities to use mentor texts to influence their writing. Borrow picture books from your school or local library. Tell your students that great writers are close and careful readers of other writers’ books, songs, poems, articles, and plays.

Informational texts can also be mentors, and in our present world, it is essential to give our students myriad opportunities to respond to social issues they would like to change. In this way, they can also try their hand at a new genre such as writing a reflection essay, a critical analysis essay, or a play.

Tempt your students to write by playing contemporary music and providing them with the lyrics. Have discussions to analyze the writer’s craft – effective repetition, and figurative language including similes, metaphors, personification, alliteration. Talk about the rhythm of the words, the rhymes and almost rhymes, assonance and consonance. Symbolism? Life lessons? It’s all there in song lyrics!

Go for sprints, not long-distance runs

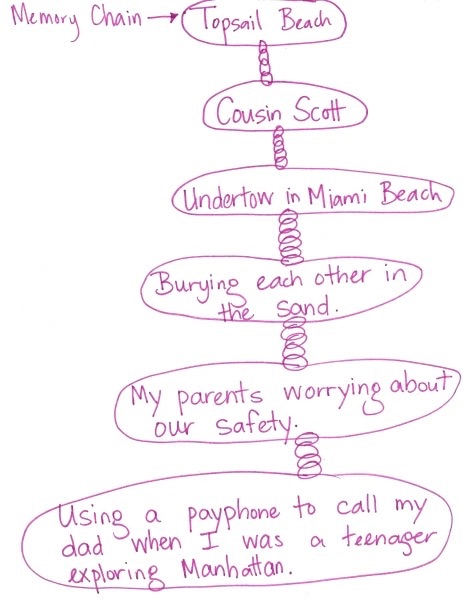

Avoid larger pieces. It’s the short bursts of writing you need to quickly evaluate how you can best help your students move forward as writers, especially if you can only find 2-3 larger periods a week to have writing workshop. Give students strategies to quickly find topics to write about – like the memory chain.

The memory chain method can effectively be used by writers as old as high school and beyond. It is my favorite way to find one or several topics to write about in my own writer’s notebook. And it can be used over and over again, sometimes starting with the same word, and sometimes starting from a new place.

Memory chains can be specific. For instance, you could start with “Christmas” and end up writing bits of memory from that one specific holiday. A memory chain, however, can span many years, events, and contain references to good times and bad times.

Using a memory chain is one strategy to discover topics that might have been overlooked by the writer or “buried” in the brain’s treasure chest of forgotten memories. Here are some simple suggestions to help you get started:

Start with a single word – a season, a day of the week, a holiday, a setting, or an object in the classroom or your bedroom at home.

- Concentrate on the word you wrote. When something pops into your mind, write it down. Sometimes, you will only need to write a word. Other times, you will need to write a phrase.

- Continue to write down the first thing you think of by concentrating on each new word or phrase.

- Do not self-edit. In other words, at this point you are not worried whether you have an idea you can write more about through one of the modes. Just get your chain down on paper!

- You can curl your chain up and down like a snake. Connect your thoughts with a line or arrow.

- When you have filled a page or are completely stuck, it’s time to stop.

- If you have enough, look for any topics that you feel an urge to write about – in story form, as an article, as poetry.

- Choose the one idea that today, in writing workshop, you are interested in writing about and have enough detail to make it interesting for your reader(s).

- Reread your memory chain several times. Look for places where another memory can spring up unexpectedly. If it does, draw an arrow and write it down before you forget it!

- If nothing comes out of this particular chain, try another with a different starting place (For example, if you started with winter, try to start with summer).

My co-author Stacey Shubitz wrote about memory chains and shared several of her own. Take a look.

Sketches of character and place

Other short bursts of writing can include descriptive paragraphs of settings and characters. Ask your writers to make a list of the people who have been on their mind a bit this year so far. The list might include classmates, family members, pets, kids in other classes, summer friends, and friends outside of school in marching band, cheerleading, gymnastics, karate, or some other activity.

Start with one person and makes some notes about the following ideas.

- What are two or three words they would use to describe the person’s character?

- What does the character want? Why?

- What is the character’s ultimate goal?

Providing students with excerpts from mentor texts or popular reads can give you a chance to have a writerly conversation about the various ways an author reveals his characters to his readers. Encourage students to share excerpts from their independent reads.

Here are some time-tested examples of thumbnail character sketches to get them started. Ask students what they are noticing about these character descriptions, then choose one or two to imitate in their writer’s notebook.

✻ From Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White

In good time he was to discover that he was mistaken about Charlotte. Underneath her rather bold and cruel exterior, she had a kind heart, and was to prove loyal and true to the end.

✻ From Just Juice by Karen Hesse

Pa never does a job right away. He likes to think about it awhile. He spends the evening puzzling out how to do the work so that once he gets the truck going and headed to the next job the next morning, he does it all perfect.

✻ From Araminta’s Paint Box by Karen Ackerman

Dr. Darling was well respected in Boston. He worked long hours and sometimes drove his buggy for miles to bring a baby into the world, or set a broken leg, or tend a snakebite. He was a very good doctor, and both Emilia and Araminta were proud of him.

✻ From Once I Was a Plum Tree by Johanna Hurwitz

Ann D’Amato liked to make plans. After her sister Rita got married last spring, Ann started making plans for her own wedding. Even though she wasn’t eleven yet, she liked to think ahead. She also liked to plan for others. So she was planning that I would marry her brother, Paul. That way we could be sisters, she said.

Our ol’ man was a traveling salesman who knew the back roads of Michigan like most of us know our own faces in the mirror. He was a flimflam man. He worked in words the way other artists work in oil or clay. Steaming all over the state in his big old cruiser, with his radio tuned to WJIM, he was a dream saver, a wish keeper. A raggedy man in unmatched socks and a worn plaid suit.

✻ From An Angel for Solomon Singer by Cynthia Rylant

A voice quiet like Indiana pines in November said, “Good evening, sir,” and Solomon Singer looked up into a pair of brown eyes that were lined at the corners from a life of smiling.

✻ From A Taste of Blackberries by Doris Buchanan Smith

That Jamie. For my best friend, he surely did aggravate me sometimes. I mean, if we got to pretending – circus dogs, for instance – he didn’t know when to quit. You could get tired and want to do something else but that stupid Jamie would crawl around barking all afternoon. Sometimes it was funny. Sometimes it was just plain tiresome.

As your students attempt these kinds of brief character sketches, you’ll be looking for common problem areas. If you’ve been an ELA teacher in the middle school for a number of years, you probably already know some things to look for: lack of subject-noun agreement, fragments, run-ons, dangling participles, lack of sentence variety/fluency, problems with punctuation such as the apostrophe in possessive plurals.

Most of these errors are grammar/conventions related. Remember that each group of students is going to be different, but chances are that some of these problems will show up each year. Immediate and ongoing feedback is going to help as well as small group instruction to offer some differentiated support. These focus groups can meet for ten minutes and so much can be accomplished.

Later on, you can re-evaluate your students’ needs and turn your attention to problems such as stamina and endurance, writing in cohesive paragraphs, using sophisticated organizational structures and logical, meaningful transitions between paragraphs, and being able to integrate their research material with their own ideas.

Virtual Writing Workshop

Many of us are teaching virtually. We can use our breakout rooms to give students the opportunity to make decisions about how they will use their independent writing time each day.

► Independent writing time should give students opportunities to try out the skills that have been addressed in the mini-lessons. Breakouts can be organized into rooms where students need silent time to write. Here, the teacher may choose to visit to observe. When you enter this breakout room, direct students to tilt their screens so that you can see the actual writing.

► Another breakout could be designated the editor’s room where students are self-editing their writing for correct grammar and usage, spelling, punctuation, and other conventions of written language. A teacher visit here may provide good formative assessment for decisions about future mini-lessons.

Have lots of writerly conversations

Remember always that writerly conversations breathe life into writing workshop and raise students to a conscious level of “I am a writer.” These conversations can be about passages from the literature they are reading in their ELA classroom or even passages from student samples from the previous year or current year, with the students’ permission.

Writerly conversations can give students a chance to notice and appropriate their classmates’ problem-solving strategies and the lens they use to read like a writer. Teacher modeling is important here as students continue to learn the language of writers to be able to talk with each other about the texts they are writing.

Follow Lynne on Twitter @LynneRDorfman and on write-share-connect, the PA Writing & Literature Project’s blog.