Helping Kids Design Personal Reading Goals

How I’m Using Design Thinking to Promote Voluntary Reading

By Katie Durkin

By Katie Durkin

In becoming a middle level English teacher, I have often found myself reflecting upon my own experience as a middle school student and budding book lover.

While I can vividly remember my myriad experiences with excellent teachers, I don’t remember having much choice or freedom in the books I read for school.

Whole class novels were assigned, we read them together, we discussed them together, and the teacher assigned a final test meant to have us demonstrate how well we understood the story.

Reflecting back on these experiences, I believe I was at risk of becoming a victim of what Kelly Gallagher calls readicide, the “systematic killing of the love of reading.” I was an avid reader outside of school, but those self-chosen books and my personal experiences as a reader remained separate from my academic life.

We know from developmental research and personal experience that adolescents can easily lose their motivation to read voluntarily. One way middle level reading teachers can counter that is to foster a love of reading through voice and choice in the classroom (Troyer, 2017 p. 2).

Design thinking can help us accomplish this student-centered teaching goal by creating space for them to engage in voluntary reading practices that will stick with them through high school and beyond.

This pedagogical approach allows students to practice the skills of empathizing, researching, communicating, prototyping, and reflecting – all integral tools in developing critical thinking and metacognition. We can also use design thinking to assure the autonomy necessary for students to create, test out, and revise their reading goals.

Bringing design thinking into my classes

When students set their own personal reading goals they are able to share what they believe to be their strengths and areas of growth as a reader. These goals, in turn, lead students to increase the range and volume of their reading because they have more choice in the selection of texts.

This fall my students engaged in the practice of setting reading goals through design thinking. To set the stage, I modeled my own reading life and goals, and then students moved into brainstorming, prototyping, and reflecting upon personal goals that would help them to strengthen their voluntary reading practices.

Modeling Before Designing

While I do enjoy reading adult books, I spend most of my time reading middle grade and young adult literature. I want to be able to readily recommend books to my students and also speak to my own personal experience with the story.

To model goal-setting with my students, I share my own preferences as a reader, as well as events in my own life that affect what and how much I’m reading. Most importantly, I’m honest with my students and encourage them to be honest with themselves as they “ideate” (brainstorm) about possible goals.

This year, when I set my goals for the first unit, I was reading a mystery novel and also planned to start a fantasy series. I also shared with my students how I was reading more nonfiction in academic journals because of the requirements for graduate classes I was taking.

In my own prototyping and testing phase, I was only able to accomplish two of these goals, and I shared with students how I revised these goals to reflect how goals may need to change. I believe this transparency shows students how adults, just like students, are thinking about how time to voluntarily read functions in our own lives.

Developing prototypes

After I modeled reading goals for my students, they were ready to move on to ideating their own reading goals and producing a prototype. I asked them three questions as I guided them through the process:

(1) What do you think you need to work on as a reader?

Then to deepen their thinking..

(2) Based upon your work as a reader last year, what do you think you still need to work on?

Then to have them shift to a goals mindset…

(3) What do you want to accomplish by the end of this school year?

Through my own goal-modeling, students saw that I worked on making more time to voluntarily read by putting electronics in another room to avoid distractions and by trying out new genres and authors. The three questions served as a guide, helping students come up with three goals – their first prototype.

My students developed these goals to accomplish before the end of a unit, but these goals could also be created for a marking period or semesters. These goals are not graded; rather, I meet with students in individual conferences to discuss their reflections and how I can help them brainstorm solutions to problems that may exist for their voluntary reading practices.

Many of my students easily created these goals as they were aware of their areas of growth as readers, ranging from having trouble finding a book they enjoy to acknowledging that they avoid larger books because they may take too long to read.

Testing the prototypes

After students created their prototype, they then tested them out each week, reflecting on how they were progressing with their reading goals. I set aside time once a week for them to look back on their work and reflect on their progress.

This gave students an opportunity to be introspective, asking questions such as: (1) What’s working well with your reading goals? (2) What do you still need to work on? and (3) What can you try out this week to continue making progress on your goals?

This reflection was repeated each week for the entire unit and provided students with a roadmap for how they were working toward accomplishing their goals.

As their teacher I also wanted evidence for how students were progressing towards their reading goals and enhancing their voluntary reading practices. Students were able to keep track of their goals in two ways. First, they kept a digital Reader’s Notebook using Google Slides that included their initial prototype and weekly reflections. But they also kept track of their goals through Reading Chronicles.

These chronicles are alternatives to reading logs and were designed to be living documents where students can reflect on their experiences as readers and connect with their peers on what they are reading. It is a digital space that can be accessed at home or school, so regardless of current learning models because of the pandemic, students were connected to each other, and to me, for support with their voluntary reading practices.

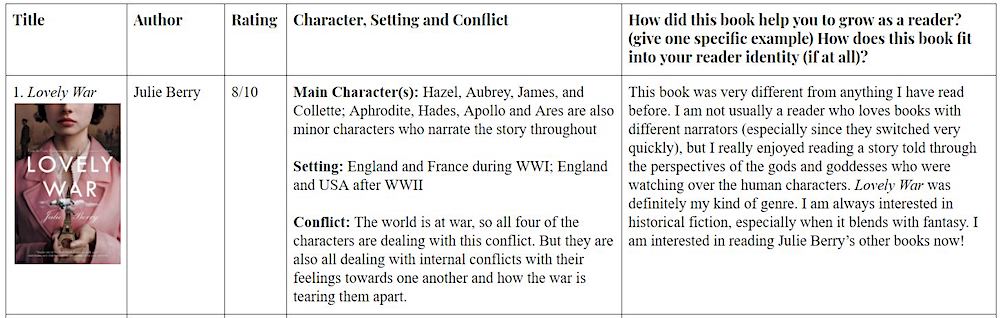

These reading chronicles showcased titles students had finished and asked them to provide basic information about the story or text. Students needed to include the title and author, create a personal rating system, include elements of the story (setting, characters, and conflict), and then offer their opinions about the book.

This opinion column included asking students to consider how the book had contributed to their reading goals and how the book helped them to grow as a reader.

Reading Chronicles and Google Slides provided concrete evidence of a student’s individual progress; it also gave them space to use their voice to explain and reflect on the choices they made with their reading lives.

Reflecting Back and Moving Forward

Finding space for students to voluntarily read is always our goal as teachers. Through the steps of brainstorming (ideating), testing out prototypes, and reflecting on outcomes, students were given the space to choose their own paths to grow as readers. When I elicited feedback from my students at the end of the unit, many of them stated they felt creating and trying out different goals was one of their biggest successes as a reader.

My students appreciated that they could be honest. Most important, they felt they had a voice in the books they chose to read and how they would grow as readers.

I plan to use design thinking with reading goals throughout the school year and look forward to seeing my students continue to develop their voluntary reading practices and begin to identify themselves as readers.

References

Gallagher, K. (2009). Readicide: How Schools are Killing Reading and What You Can Do About It. Stenhouse Publishers.

Portnoy, L. (2020). Designed to Learn: Using Design Thinking to Bring Purpose and Passion to the Classroom. ASCD.

Troyer, M. (2017). A mixed-methods study of adolescents’ motivation to read. Teachers College Record, 119(5), 1–48. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.neu.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2017-30196-004&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Viking Books for Young Readers. (2019). Lovely War [Hardcover Book]. Amazon. https://www.amazon.com/Lovely-War-Julie-Berry/dp/0451469933

Dr. Katie Durkin (@kmerz610) has been teaching English Language Arts to middle school students for a decade and currently teaches 7th grade Reading Workshop at public Middlebrook School in Wilton, Connecticut.

Katie is a zealous reader of middle grades and young adult books and enjoys sharing her love and passion for reading with her students. She is a doctoral student at Northeastern University studying the impact of classroom libraries on middle school students’ reading engagement. She is the 2020 recipient of the Edwyna Wheadon Postgraduate Training Scholarship from the National Council of Teachers of English.

Katie recently completed her doctoral degree at Northeastern University, focusing on the impact of classroom libraries on middle school students’ reading engagement.