Teach Your Students to ‘Explode’ Complex Text

By Sunday Cummins

✓ Evidence cited without explanation.

✓ Vague reasoning with little elaboration.

Does this sound like some of your students’ responses to informational sources? This may be because they do not have a strong grasp of the content in the source.

What can you do? Introduce students to the “explode to explain” strategy. When students “explode to explain,” they closely read a key sentence or two in a source, annotate, and practice explaining what they are thinking and learning. Here’s how it looks in the classroom.

Respond Together

The first time I share this strategy with students, we do it together. In a lesson I gave with a small group of fifth grade students, the students read a Newsela article about communities in Australia using drones to patrol for sharks in the shallow waters near beaches.

As a group, we determined that one of the main ideas in the article could be summed up this way: the communities are using new technology in innovative ways to protect swimmers.

With my guidance, the students chose a sentence that supported this main idea for the “explode to explain” experience. The sentence is actually a quote from the president of a local surf lifesaving club, Romilly Madew:

“The reason the drone is so important is sometimes we can’t see over the waves, so having the drones is that extra little piece of prevention for us.”

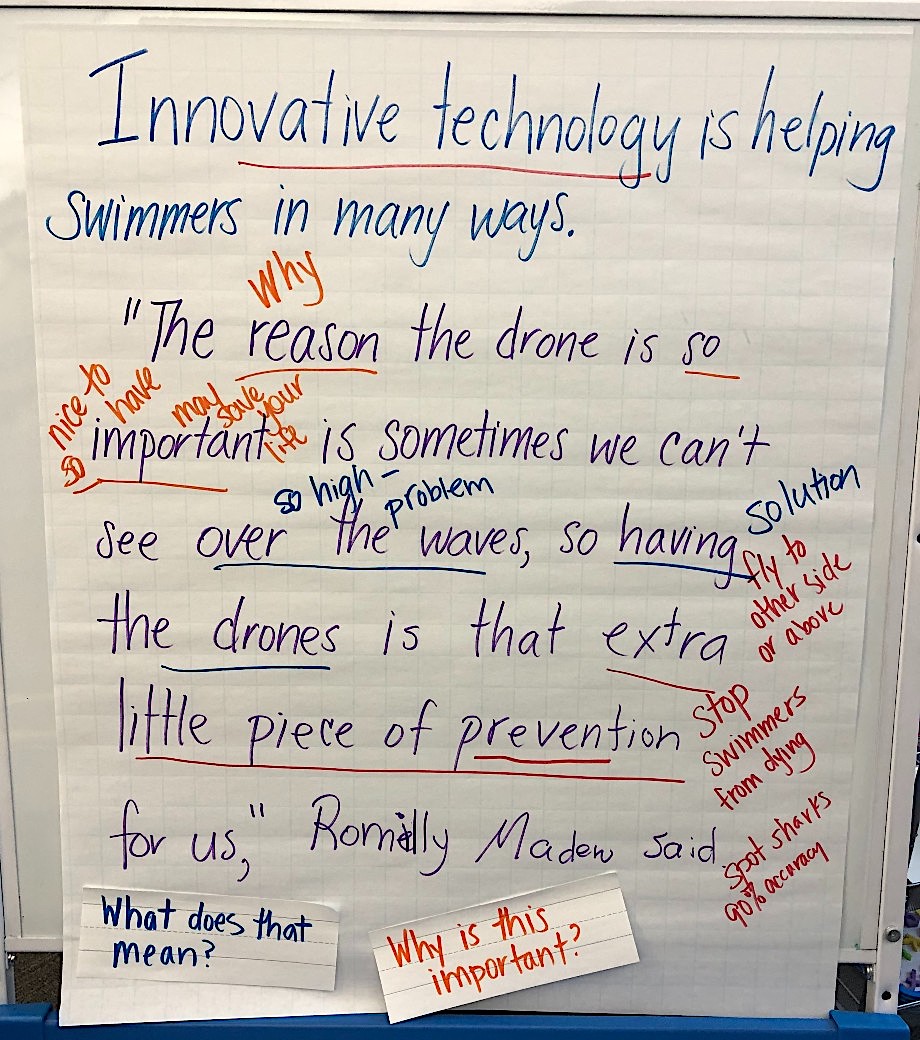

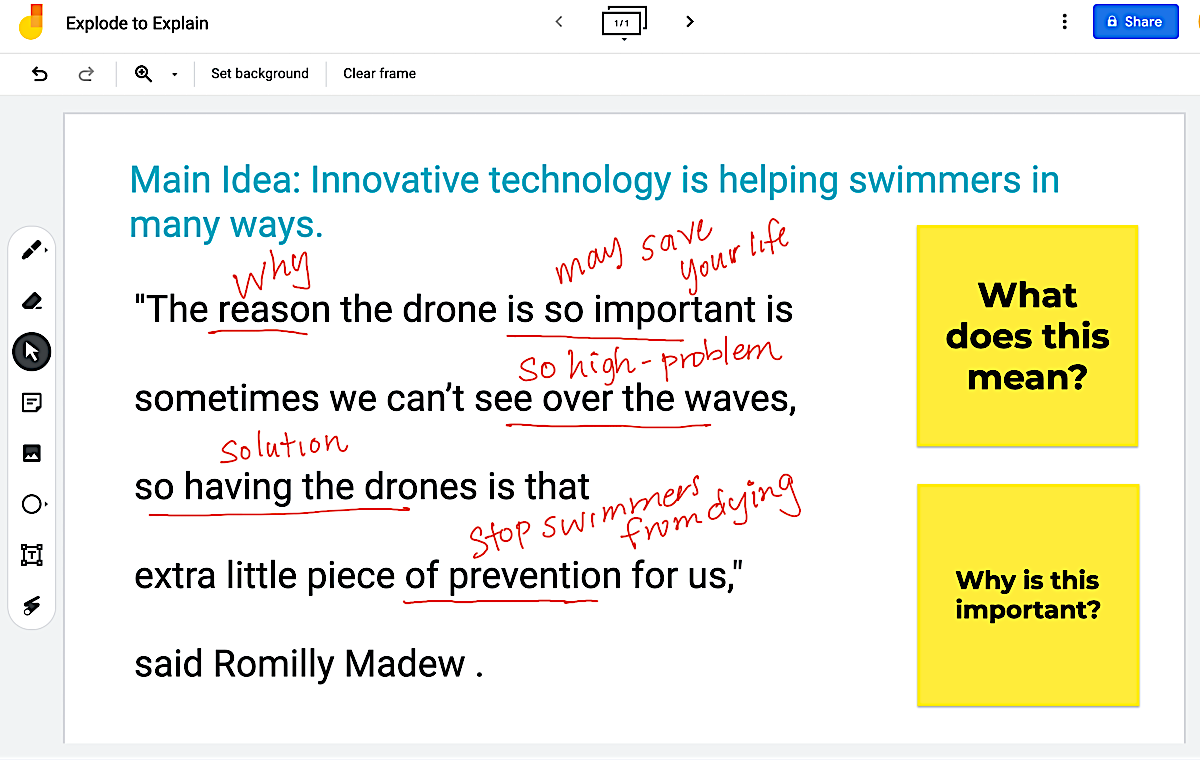

This was a pre-Covid face to face lesson, so I copied the quote on chart paper for all students to view. (See figure 1) If you are teaching virtually, you might use Jamboard or a similar tool instead. (See Figure 2)

We started at the beginning of the sentence, stopping along the way to discuss words or phrases that jumped out at us as important. I served as the scribe, annotating the text, making the students’ thinking visible for them.

We noticed “reason” which signifies that Romilly Madew was going to share why the drones are critical. Then we thought through why not being able to “see over the waves” might be a problem for swimmers and how the “drones” are a solution to this problem if they can fly to the other side of a wave and see what swimmers cannot see.

We also discussed the meaning of the word “prevention” and how it applies in this context: the drones spotting sharks may stop swimmers from dying. The students also made a connection to a key statistic quoted earlier in the article about how the drones can spot sharks with 90 percent accuracy.

During this whole conversation, I am also saying (almost exclaiming), “Wow! Isn’t this amazing? I mean I’ve heard about drones, but I didn’t know…. What are you thinking about this?”

I want them to realize that as they engage in thinking through the details, they also need to be responding personally to these details (“what’s interesting or useful to me?”). Responding personally will help students retain this information, but more importantly, responding personally engages students in seeing how what they are learning can be a transformative experience.

Practice Explaining

Next students need to practice using the annotations to summarize their learning and thinking. For this lesson, I started by thinking aloud for the students in two ways. I thought aloud about what I learned AND about how I used annotations to help me share what I learned. It sounded like the following:

Wow. I learned some fascinating things in this article. I need to think about how I can share what I learned in a way that makes sense to someone who has not read this article. I think first I’ll talk about what the main idea of the article was and then I’ll talk about what Romilly Madew, the president of the surf lifesaving club said. Let me see. [Pause to look carefully at annotations.] Okay. Here I go.

In Australia, where they have lots of sharks, they are using new types of technology like drones to keep swimmers safe. The author of the article interviewed the president of a local surf lifesaving club who [point to the first annotation] explained why the drones are helpful. [Pause and point to the third annotation.] Sometimes the waves are high and the swimmers cannot see past the waves. That sounds really dangerous, huh? But they are using drones to… [Stop and look at the students.] What else might I add to this?

Some students, including our emergent bilinguals, may need to practice doing this a few times.

Repeat

After we engage in an “explode to explain” together, I ask students to choose an additional sentence from the source to copy in their notebooks (with spaces between lines for room to underline and jot notes). In some instances, I might provide a sentence (copied in larger print on individual sheets of paper).

We may start to annotate together and then gradually I release them to annotate on their own. I confer with individuals as needed. Afterwards, I ask students to talk about why they decided to jot particular notes for annotations and why that was helpful.

I close by asking partners to talk with each other about what they learned. I encourage them to refer to their annotations as they do so.

Coach for Transfer

Again, if students can explain what they learned in their own words, they are more likely to remember this information. When they return to the article for additional information to support the main idea, they may understand other details better as well. All of this can make writing about what they learned easier, too.

As a teacher, I do not want “explode to explain” to become a tedious activity for my students. Instead, I want students to see the power of rereading thoughtfully to make sense of a complex sentence or idea.

I actually ask students, “Why engage in ‘explode to explain’?” We talk about how doing this does not mean you always have to copy a sentence and annotate heavily. It may mean that you just slow down and reread, thinking carefully about what is being said or implied, pulling apart the words in your mind, sometimes noticing how a detail changes your understanding of the topic, and mentally preparing for how you will explain your thinking to others.

References

Agence France-Presse. (2017, December 20). Aerial patrol: Drones used to spot sharks on beaches in Australia. Agence France-Presse via Newsela (Ed. Newsela Staff. Version Lexile 1070).

Sunday is the author of several professional books, including her latest releases, Close Reading of Informational Sources (Guilford, 2019), and Nurturing Informed Thinking (Heinemann, 2018).

She’s is a graduate of Teachers College, Columbia University, and has a doctorate in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Illinois, Champaign Urbana. Visit her website and read her regular blog posts on teaching information literacy. Follow her on Twitter @SundayCummins.