Talking to Our Students about the Capitol Riots

And then, on Wednesday, rioters stormed my country’s capitol to protest the election of 2020, with hundreds breeching doors and windows and roaming freely through congressional halls.

I return to school on Monday, January 11. And when I do, albeit remotely, what will I say? What will my 8th graders be thinking? Where will their heads be, five days after this historic event?

I do know that it will be impossible for me to say nothing, and to instead plunge ahead with my regularly scheduled content. To say nothing says way too much.

Making connections

I’ve lost count of the “unprecedented” events of this year. This appears to be yet another “unprecedented” event. Or is it?

As history teachers, what are we doing if we are not making connections between past and present? People have used the word “shocking” to describe what happened. Certainly, it was shocking. But it was not particularly surprising.

Like anything in history, there were causes and there will be effects. So one idea I’m playing around with is having a discussion where we consider some of the causes. And then we can follow up with questions and ideas about some of the possible effects in both the short term and long term. What will the history books say? What will my students tell their grandchildren?

A few pieces of advice for this week:

► Don’t be afraid to say, “I don’t know.” Even if you’ve been glued to the news for days, you will not know everything. If they have devices, have students look things up for you while you move on. When they report back, ask them what source they used in order to model the importance of considering the source.

► Give space to students. Let them ask questions and express their views. Consider basic ground rules for respectful class discussion.

► Consider perspective. Here is where things can get dicey and will vary widely among us depending on the political persuasion and racial/ethnic makeup of where you teach. It is always good to remind students, especially if you teach in a community that skews predominately in one political direction – whichever that direction might be – that students a few towns or counties over might be having a very different point of view.

► Provide context. Here is where you can help students work through what happened by providing the background they might need or puzzle over when it comes to protests/riots of the past, presidential elections and presidential transitions.

► Raise questions. Again, it is okay if neither you nor your students know the answers. Our job as educators is to help students think by posing thoughtful questions. A few are below. Also see the questions at the PBSNewshour link at the end of this post.

- What does this moment tell us about political division in this country?

- What does it tell us about racial division?

- What does it suggest about the role of social media? The selfies taken? Trump’s tweets?

- In what ways do the words we use matter? Lies vs. untruths, riot vs. protest, insurrection, coup, uprising, terrorists?

Other directions you can go

What one does in the classroom on the day of or day after a major event can be quite different from a few days or a week later. Each of the items below can be developed into an entire lesson as a follow-up:

Rioter in military gear with plastic cuffs ID’ed as AF combat veteran. (New Yorker)

► One of the major issues raised by what happened is the disparity between how police and the National Guard interacted with Black Lives Matter protesters compared to the events of Wednesday. This article from the Guardian has some useful images. This day-after editorial from the Washington Post raises interesting questions about “what if” there had been greater police force.

► In the speech he gave on the afternoon of January 6, Biden said, “Let me be very clear. The scenes of chaos at the Capitol do not reflect a true America, do not represent who we are.” To what extent is he right? To what extent is he wrong? Polling suggests a significant number of Republicans believe the election was rigged despite many court rulings upholding the vote. What is a “true” America?

► What is the Alt-right? What is Antifa? What role have these groups played in the events of the last few months? What is a conspiracy theory? What is the relationship between the Republican party and white supremacy?

► Politics vs. statesmanship: putting one’s political interests ahead of those of the nation. Is the Democratic plan to impeach appropriate? Politically astute? What about the members of Trump’s cabinet who are resigning? Are those resignations making an important statement about the right thing to do? Are they too little too late? Are they to avoid having to vote on the 25th amendment? What would you need to know in order to make a judgment?

What will you do in the days after?

While the repercussions of Wednesday’s events will likely percolate at least through the Inauguration, at some point you are going to want to return to your regularly scheduled curriculum.

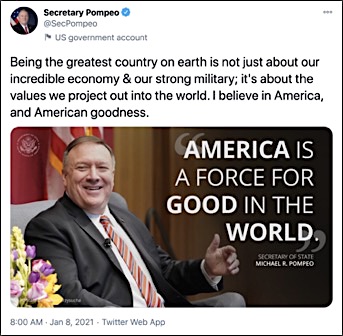

For me, I will be just starting a new unit on U.S. foreign policy. One of the major themes we discuss in that unit is the idea of nationalism vs. patriotism and the connection to American Exceptionalism. Many politicians, including Biden and Trump, referenced these ideas on Wednesday. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s tweet on Friday morning positively screams this:

In order to set up my new unit, I might introduce these themes, show this tweet and ask students why Pompeo might be tweeting this just two days after the riot.

So think about what unit you are in the middle of or just starting. Here are just a few connections:

- The Civil War: to what extent do the events of Wednesday connect to the divisions facing the U.S. before the Civil War? Are we in a “cold” Civil War? Is a “hot” Civil War possible? Consider the photograph below and the significance of the portraits on the wall. Read this article about the connection to the caning of Charles Sumner (whose portrait is in the center).

- Comparisons to the violence that broke out in the Women’s Suffrage March on Washington in 1913 just before Wilson’s inaugural. The D.C. Superintendent of Police lost his job over this incident.

- Civil Rights protests: consider Dr. King’s argument in support of nonviolence in Letter from a Birmingham Jail. Have students reflect on this quotation from James Baldwin: “We call it riots, because they were black people. We wouldn’t call it riots if they were white people.”

- Impeachment is an obvious connection, if you are in a unit on the Constitution or Reconstruction.

- Other constitutional/political topics: balance of power, the role of political parties, the election process, inaugurations, presidential transitions. The tweet below from 11th Hour could serve as a discussion prompt.

Deep breaths

And while I ponder my own advice, deciding what exactly I will be teaching on Monday, I will try to relax. As teacher Dennis Urban recently put it on Twitter.

https://twitter.com/DrUrbanTeacher/status/1347255915951628291?s=20

Exhausting, yes. But as I return to the fray on Monday, I am reminded again how much of what we do as history teachers matters. We will always have a role as keepers of the meaning.

A few useful sources:

► Facing History – Responding to the Insurrection at the US Capitol

► From Huffington Post – Teachers Grapple With Discussing Capitol Riot With Kids During Already Unstable Year

► Classroom resource: Three ways to teach the insurrection at the US Capitol – from the PBS Newshour, which is where you can also find a link to this resource from #sschat.

► Lesson ideas from Dr. Noor Ali, a principal at a private school in Massachusetts.

I just saw this on Twitter–a listing of op-ed pieces and columns by historians written about the Capitol riots. Looks like it will be updated, too. http://www.megankatenelson.com/historians-contextualizing-the-capitol-insurrection-a-roundup/

We would also recommend the NYT op-ed by Brent Staples, “The Myth of American Innocence” for perspectives on voter suppression in Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/09/opinion/capitol-attack-racism-america.html