Translanguaging Lets MLs Use All Their Tools

A MiddleWeb Blog

Each language is a tool for learning.

Each language is a tool for learning.

Describing someone as having a single-language repertoire means they have a single language toolbox with various languages inside.

Each language we speak is an individual tool in the box that we can use for different contexts, purposes, and audiences.

Some tools are used to break things down while others are used to put things together. Just as the context determines the kind of tool we should use, context also determines the language people use.

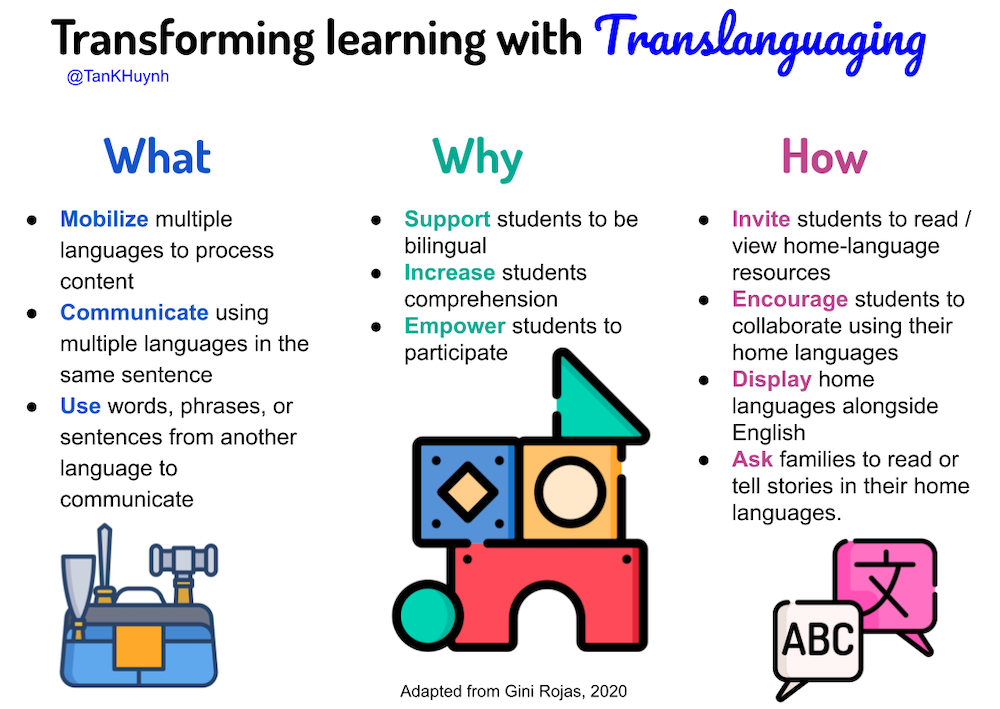

What is translanguaging?

Translanguaging is the “strategic use of one language to facilitate the acquisition of the other while immersed in subject-area classes” (Garcia & Tatyana, 2016). The purpose of translanguaging is to empower a person to be multilingual. People “translanguage” when they:

- Mobilize multiple languages to process content

- Communicate using multiple languages in the same sentence

- Choose words, phrases, or sentences from another language to communicate

Why should students translanguage?

Many families from diverse backgrounds want to send their children to school to become multilingual, not to lose their home language in order to acquire English. Translanguaging provides a pathway to acquire English while maintaining and sustaining students’ other languages.

Being multilingual is an asset that must be nurtured, not erased. Multilinguals are able to immerse themselves in different cultures, and through this process they develop the ability to view the world from different perspectives. This skill is essential to being a global citizen as people who are perspective-seeking are less likely to be conflict-oriented (Soltero, 2016).

Additionally, being literate in one language supports literacy development in another language. The skills we acquire as we become literate in one language (e.g., sustaining emotional stamina, processing text, producing text, organizing ideas, using transitions, reading with intonation, etc.) can be transferred to another language (Cummins, 1974).

Lastly, encouraging students to translanguage is an act of anti-racism. Teachers explicitly communicate that all nationalities are equal and welcomed at schools. Translanguaging helps students realize that English is not the only language of value. When we force students to only speak one language, it limits their participation, which expands the achievement gap.

We want to avoid using language as a reason to segregate a group of students from participating with others. If we segregate by language use, we are contributing to the institutionalized racism often found in our systems of schooling.

When is translanguage appropriate?

Students can use translanguaging to access grade-level content. When a teacher, for example, is teaching in English about the process of photosynthesis, a student can use a home-language text about photosynthesis to establish comprehension and close gaps in misunderstandings.

Translanguaging helps students increase their comprehension of the subject matter so that they can participate in class. And it is participation that will increase their engagement and lead to higher levels of achievement.

Translanguaging moves the students’ experiences from can’t to can. They simply cannot fully participate in English… yet. But for now, they can certainly still engage if they are given the opportunity to understand the content and process the instructions in their home language.

Encourage students to translanguage when:

- they need to understand a vocabulary word

- they do not understand the instructions

- they have to process a text or video

- they want to communicate their ideas

- they have to express a need

Forcing students to only use one language not only handicaps them but prevents them from engaging fully in the class as an equal and valued member. When this happens, unfortunately, their assets and talents are hidden from our view, further perpetuating the limiting, can’t-based narrative around language learners.

Gini Rojas says, “Translanguaging is the can. Not only the can, but can do at grade level.”

How can teachers support translanguaging?

The degree to which students translanguage at school is determined by teachers. When teachers encourage it, students are more likely to do it. When some teachers demonize students’ home languages, students will begrudgingly default to English. In the worst-case scenario, students will internalize that their languages and cultures are not as valuable as the English and Anglo-Saxon cultures.

For example, a student enrolled in a school with an English-only policy may perceive English as superior to their home language, and when at home, they will prefer to speak English instead of their home language. With the gradual weakening of their home language usage, the student will lose a valuable connection to their culture.

Teachers can nurture a classroom environment that celebrates multilingualism by:

- Having students compare a language concept in English to their home language

- Providing a translation of key vocabulary in students’ home languages

- Displaying work produced in the home language

- Inviting students to collaborate using their home language

- Encouraging students to use home-language texts and videos to process content

- Suggesting to students to write in their home languages

Teachers can be monolingual yet still support multilingualism. Educators do not have to know the language to invite students to engage in content using their home languages. They just have to think of students’ languages as toolboxes, and they have to teach students to figure out how each tool works and when to use it.

With translanguaging, context is key.

In the end, translanguaging is less about languages and more about mindsets. Teachers who are inclusive of other cultures and communities are more likely to create space for translanguaging. These teachers have an assets-based mindset – they focus on what students can do with their entire language toolkit instead of focusing on one tool for all tasks.

We and our students stand to gain much from encouraging students to use their home languages at school. Our students and their communities stand to lose everything if we don’t.

References

García, O. & Tatyana, K. (2016). Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments. Routledge.

Cummins, J. & Gulutsan, M. (1974). Some effects of bilingualism on cognitive functioning. In S. T. Carey (ed.), Bilingualism, biculturalism and education. Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press.

Rojas, V. (2022) In Response to English-Only: A Translanguaging Call to Action. The International Educator.

Soltero, S. W. (2016). Dual language education: Program design and implementation. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

What’s the difference between translanguaging and simply not speaking languages properly? Is there any evidence that learners end up speaking the actual language being learned better? I’d love to see the reports about its net impact!

Cathy, I believe Dr. Rojas was not talking about how students speak but instead on what resources can students use to help them speak. I myself had to learn English as a second language during middle school, and up to this day, as an adult, I still use my Spanish vocabulary knowledge to help me speak or write in English. I believe that Dr. Rojas sees the first language as a tool to help learn and increase the second or third language. The first language should be used as a tool because if the student speaks or reads in their first language, the vocabulary, and language skills are transferable to their next languages. For example, if you are teaching Third grade, and students are learning about the Californios and the Missions, why not have students read something in Spanish at their level? the knowledge is transferable and the students would not only understand/learn but they can also become leaders and use their knowledge to teach other students.

Hi, Cathy y hola Liliana.

The three points that Liliana shared are correct. It’s less about pronunciation but about accessing content through students’ home language. I know 5 languages and each language helps me understand how to speak the other one better because I get to use the features of one language to understand the other.

For example, I never realized that many adjectives in English end with the suffix of “ed” (e.g. rooted, soaked, colored, ripened). I thought “ed” always meant the past tense. However, when I started to learn Spanish in middle school, I realized that Spanish had suffixes for their adjectives (e.g. esposado, limpiado, cansado) just like English. I started then improve my reading comprehension in Spanish with this knowledge and I also began writing more effectively in English because of this concept.

The research that you mentioned can be found in the references I have provided at the end of the article.

Thank you for reading and commenting on the blog. Wishing you health and happiness.

Thanks Tan and Liliana. I guess I was thinking something like Singlish, that maybe it just means you never learn the other language as a standalone.

The idea that you extrapolate from things that happen in one language to another totally makes sense!

May I gain permission to use your visual in a book chapter I am writing?

Author Tan Huynh responds: Yes, by all means! Please let Dr. Telford know that there’s a blanket permission to use anything I share with full citation. No need to ask.