Helping Our Students Think About Thinking

Reflecting on their work gives students an opportunity to look back at what they have done, to examine the processes and strategies they used, and to think about the importance of their effort and growth.

We want learners to understand that being reflective means to be curious about our own thinking and to come up with ways to express or name the thinking so others can learn from this. Reflection offers students the chance to slow down, consider the important work they have been doing, and see themselves as the authors of their own learning.

Peter H. Johnston, in his wonderful little book Choice Words, calls this understanding agency – “a sense that if they act, and act strategically, they can accomplish their goals.” (pg. 29)

Why Reflection Is Important

The practice of reflection can place the learner at the heart of the learning. The student understands that what he did and how are key to his continual growth and learning, and the process of reflection makes this learning visible.

Reflection also means applying what we’ve learned to contexts beyond the original situations in which we learned something. A question we ask our students might be, “When or where do you envision using this scaffold/strategy/skill again?”

Structures to Promote Reflection

We have many opportunities to create an experience that will give our students a chance to reflect on their writing and share their thinking with classmates and their teacher.

Sometimes writers will use a whole-group conference to share a strategy, procedure, or craft move that worked well during the writing process, and sometimes we offer up the problems and roadblocks to our success, hoping to get some helpful suggestions from our writing/reading community.

Sharing with Inner and Outer Concentric Circles

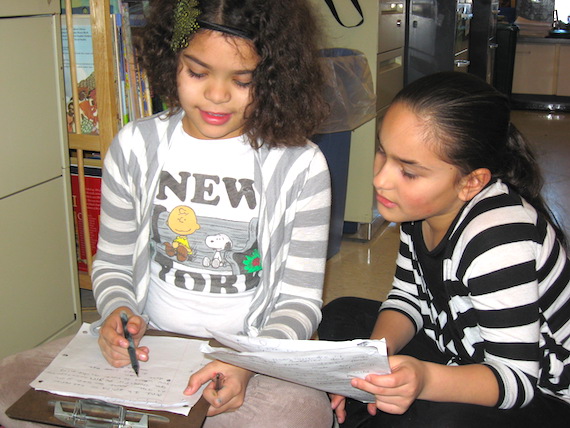

There are many ways to help students hone their reflection skills. Students can form an inner and outer circle. Students on the inside circle can sit facing the students on the outside circle. After students have had time to share their writing piece or a response to reading, the students on the inside circle can shift to the right or left to continue to share with a new partner.

Students should orally praise each piece and write a suggestion for revision on a sticky note and give it to the writer so that revision can be considered. Sometimes, we can ask students to share their entire piece on a first read for specific praise from a peer, and then only read a specific part of their piece in a second read to receive a helpful suggestion for improvement.

The teacher chooses a spot to sit, observe, and take some notes. What reflections for improvement were offered? How could these reflections be improved? Finally, how do the authors of the piece choose which suggestions they will use to move forward as writers? During this kind of discussion, the teacher can take notes on an anchor chart and students can continue to add their thinking as they consider revision possibilities (Dorfman & Dougherty, 2017).

Four Quadrant Response

Four quadrant response is a way of gathering responses to a literature selection, article, or essay and layering meaning at the same time. It is a wonderful strategy to get students reading, writing, thinking, and sharing through the written conversation they have with their group members.

Although a four-member group is ideal, it certainly will work with two or three students. When each person gets his own paper back filled with responses, he can take it to another group or whole class discussion and share some new insights with confidence.

Four quadrant response places ownership for extending thinking and questioning the text on the students through a silent conversation that uses writing as a powerful tool to make meaning. Here is the basic structure:

- Students divide their papers into four equal squares.

- In the top left corner, they mark a small x or write their initials to identify the owner’s writing space.

- After reading a short story, a poem, a chapter, or a news article, the student writes his comments only in that upper left-hand box. He may write his wonderings, connections, opinions, thoughts, and feelings. He may agree or disagree with the text or try to clarify what is confusing or puzzling.

- The students in the group of four all pass their papers to another group member, usually in a clockwise fashion.

- With the new paper, each student carefully reads and responds to the writing in the upper left-hand corner, filling in one of the empty boxes.

- The group passes again. This time there are two boxes to read, but the reader still responds to the writing in the upper-left corner.

- The group passes again and repeats the process.

- Finally, the owner gets his paper back and can read all the responses from his group. It may change his thinking or it may layer the thinking.

- The original owner may want to write another response or final comments on the back of the page.

These quadrant responses can accompany the students to their small groups, often assigned by the teacher. They can be used to help enrich a discussion among a new group of students. These sheets can also be used to informally assess the thinking and comprehension skills and strategies of the students in the class.

Rubrics and Self-Assessment

Ayres and Shubitz (2010) suggest copying both sides of a paper with a rubric so that teachers and students can use the same tool to evaluate a piece of writing. They also recommend a space for students’ comments so that students are able to support the decisions they make during self-assessment with evidence from their text.

As student writers engage in the process of self-assessment, they are able to re-envision their work, finding the tracks of their learning in the pieces they are writing, and sometimes discovering that a piece they thought they had finished has possibilities for revision and editing.

When we offer students the opportunity to examine their writing with the same tool, we will use [[[ is there a word missing here or nearby? ]]] to offer praise and polish (and sometimes, a grade), we build a quality culture for the drafting process. If we believe that reflection and goal setting is important, we will make time for it daily.

Reader Response Journals

The goal of discussion in book clubs, literature circles, and whole-group conversations about a read aloud or shared reading experience cannot solely be participation. While we hope all our students will contribute their thinking, we must redirect their attention to gaining perspectives and making meaning of the text.

When students notice the ways others problem solve and think about a text, they can revise their own thinking in some way. Using the strategy “Think-Ink-Pair-Share,” students can hold their thinking in their notebook and possibly revise their thinking – adding to it in some way or even changing it – based on the thinking their classmates have shared.

It may be important for us to stop and reflect on the degree to which our students are changing or not changing their thinking after a rich discussion. Giving students a chance to return to their journals to do some revision of their first thoughts is one way to check in to see how students have gained a deeper understanding after participating in “grand conversations” (Eeds & Peterson, 2007).

Students articulate their construction of meaning and change it as they hear other perspectives and participate as active readers – predicting, hypothesizing, and confirming or changing their predictions as they read. It will be important for our students as they become leaders in a global society to consider other people’s thinking to enlarge their universe.

Thinking about thinking, together

Building reflection time into all learning helps both teachers and students. If teachers model writerly behaviors, including reflection, we demonstrate that we believe reflection is important. Metacognition, thinking about our thinking, is a way for us to grow as educators.

If we teach students to understand the standards and track their own progress, we provide a lifetime of opportunities. We teach students to reflect on what they know based on the standards and their use of evidence from their reading and writing notebooks, portfolios, class anchor charts, class minilessons, and class discussions. In turn, this helps teachers understand where their students are and where they need to go next.

References

Ayres, Ruth & Shubitz, Stacey. 2010. Day by Day: refining Writing Workshop Through 180 Days of Reflective Practice. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Dorfman, Lynne & Dougherty, Diane. 2017. A Closer Look: Learning More About Our Writers with Formative Assessment, K-6. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Eeds, Maryann & Ralph Peterson. 2007. Grand Conversations: Literature Groups in Action. Scholastic Teaching Resources, Updated Version.

Follow Lynne on Twitter @LynneRDorfman and on write-share-connect, the PA Writing & Literature Project’s blog.