Freeing Students to Write What They Know

Writing to texts and prompts has silenced student voice.

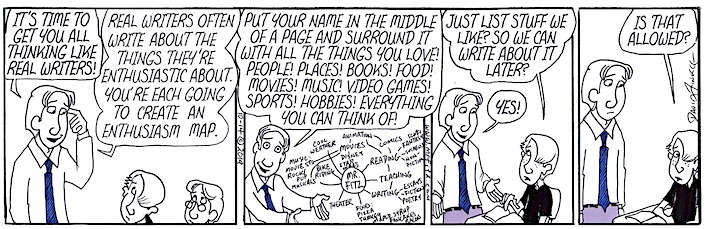

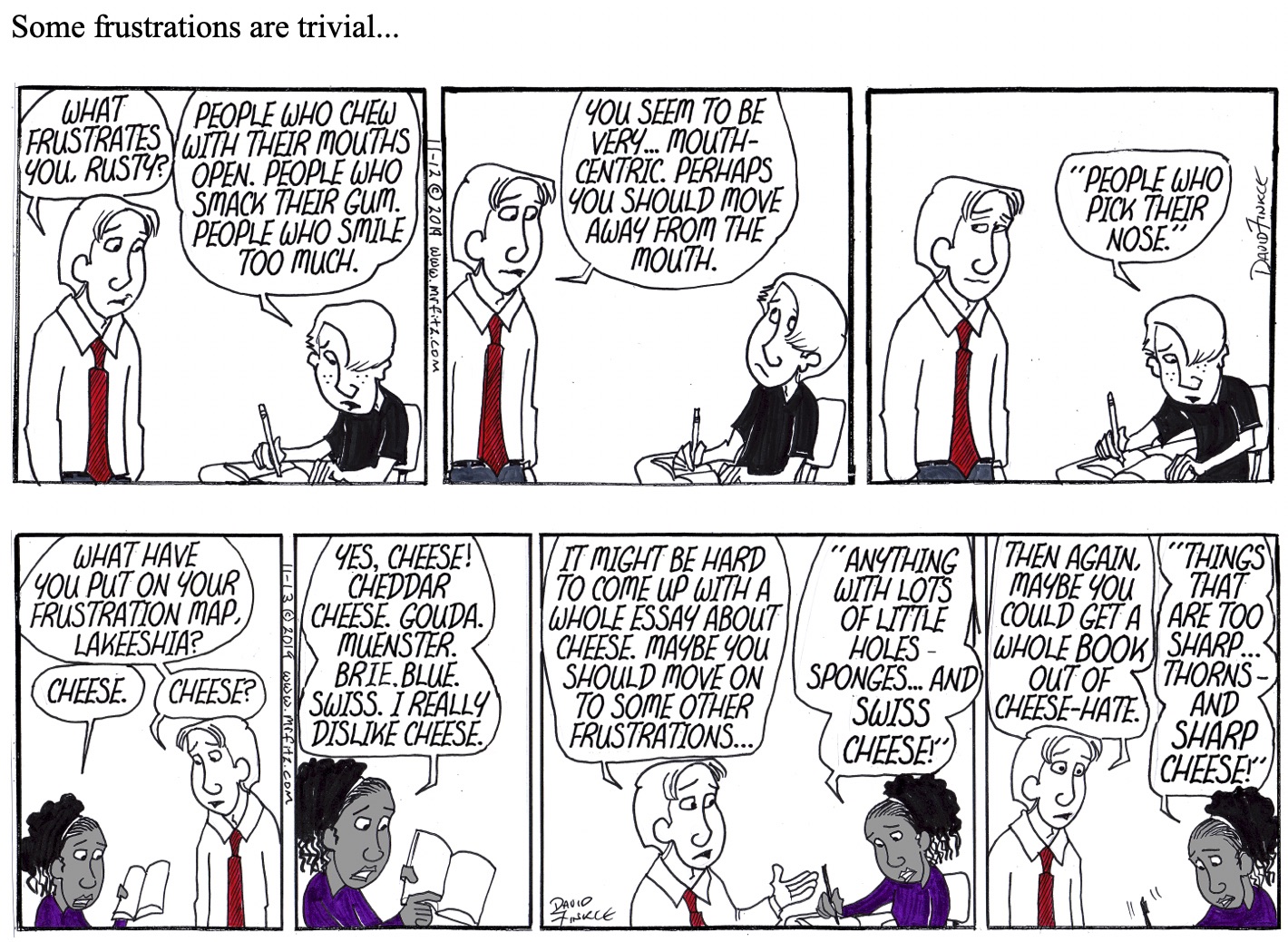

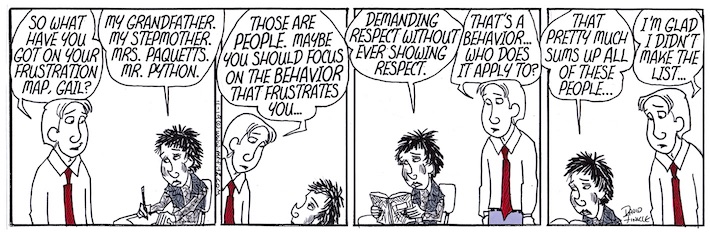

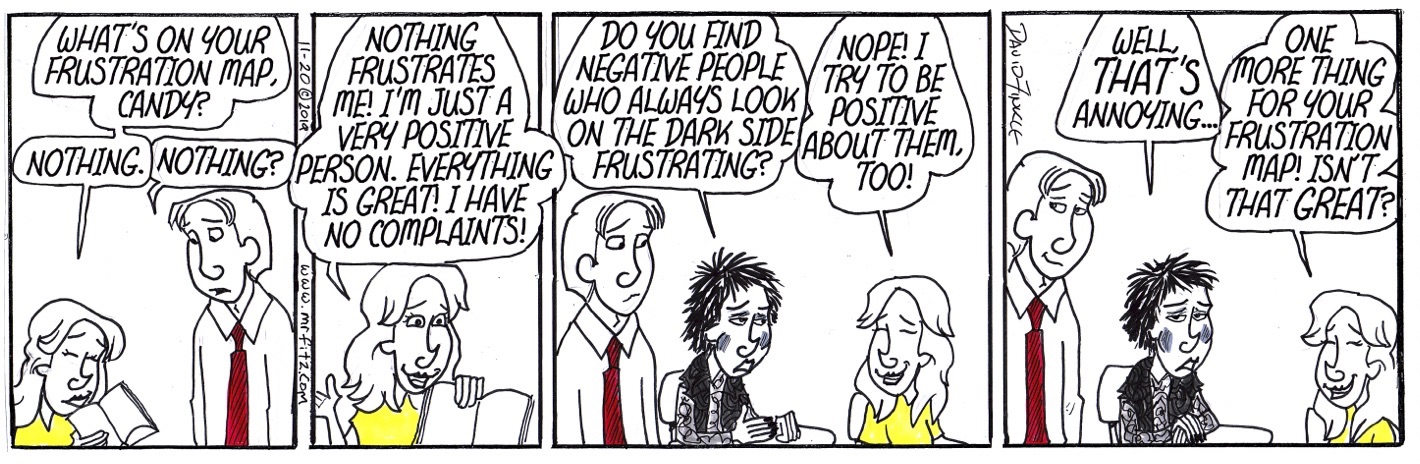

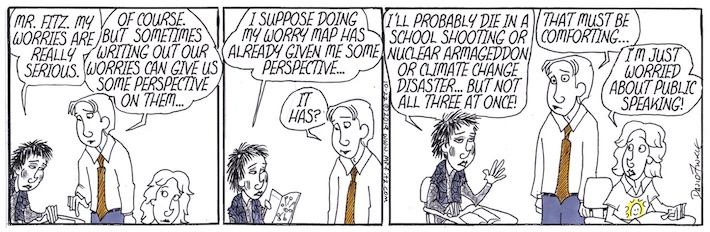

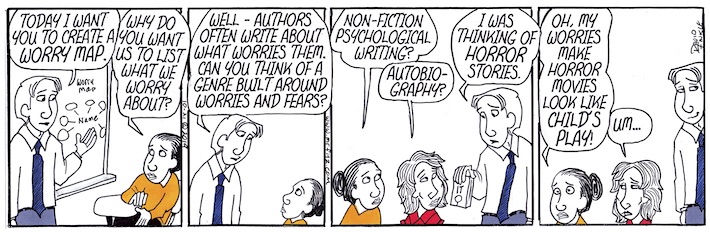

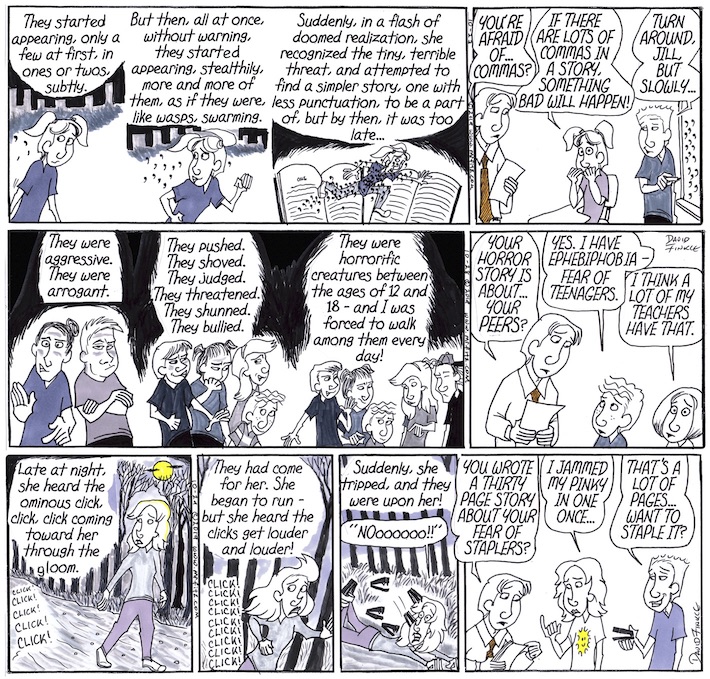

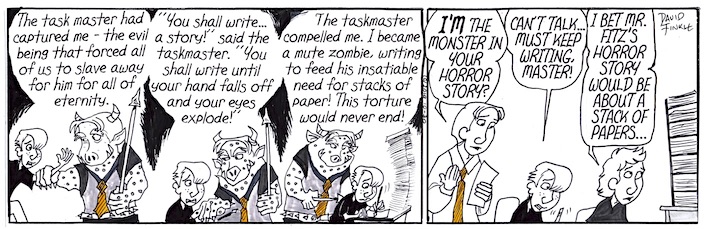

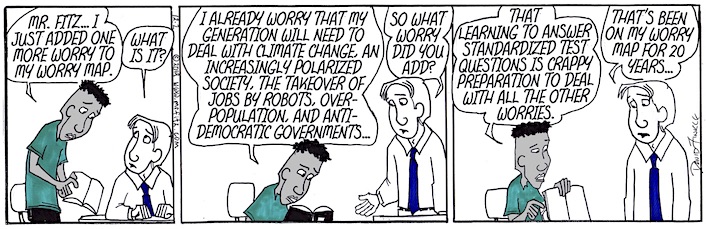

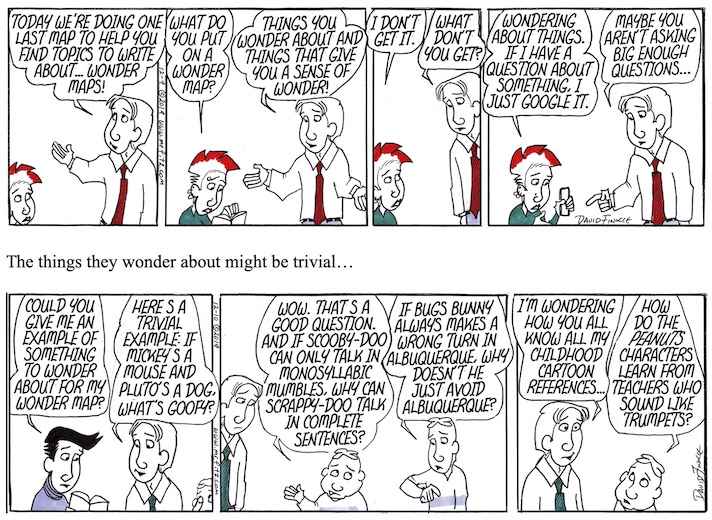

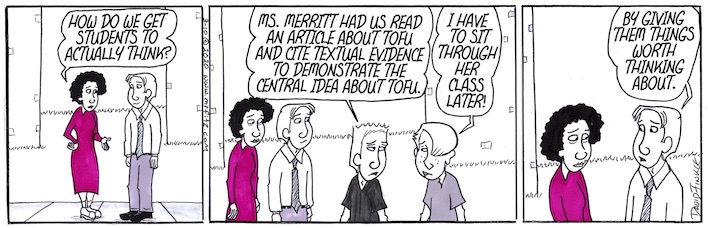

All Mr. Fitz cartoon strips by David Lee Finkle – click to enlarge

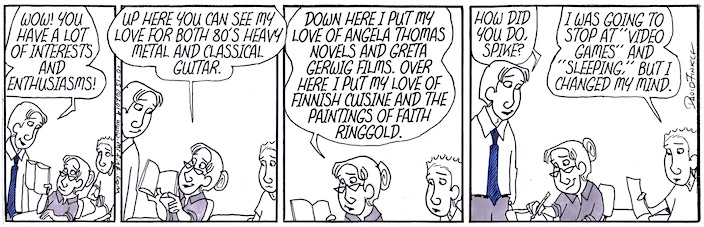

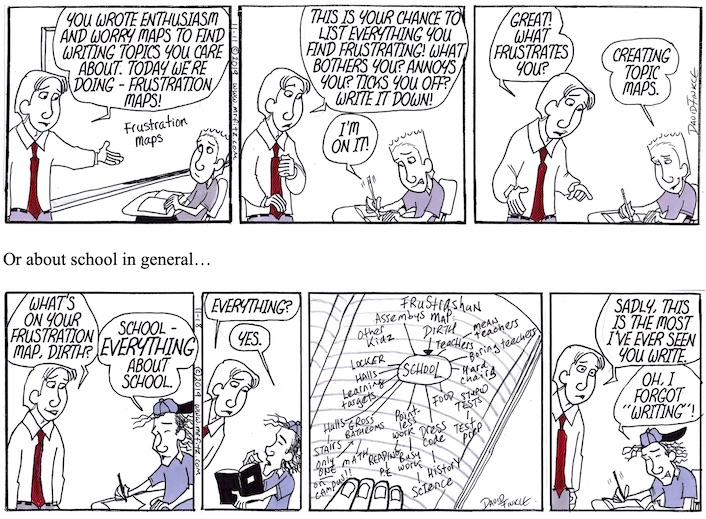

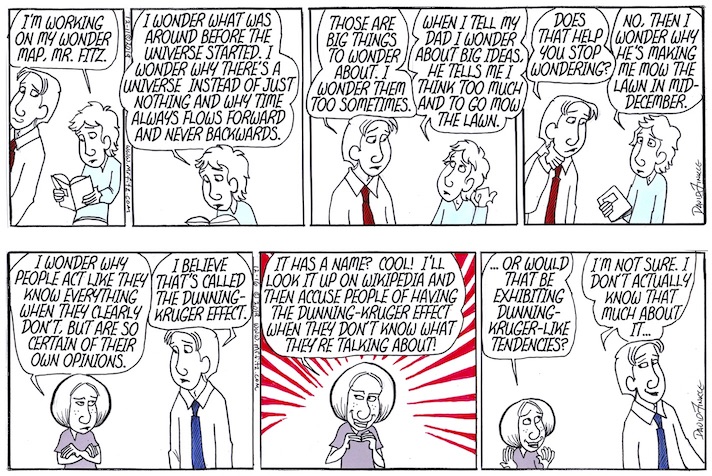

All Mr. Fitz cartoon strips by David Lee Finkle – click to enlarge

By David Lee Finkle

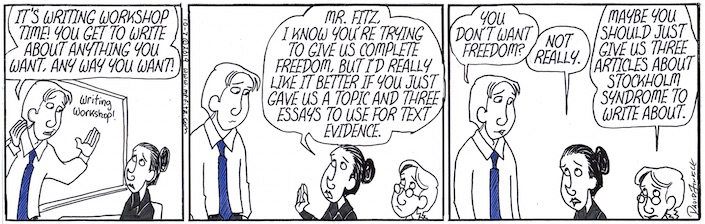

As a teacher-cartoonist who writes about the classroom, I’ll admit I use a lot of hyperbole and caricature. The strip above, however, did not involve much exaggeration.

While many of my students appreciate the chance to be set free to write about whatever they desire, many of them find the freedom terrifying rather than liberating.

Part of the terror comes from the way school systems have emphasized grades and scores and GPAs over learning and risk taking. Part of the terror comes because, in the age of Common Core, many students have been taught to write under the “instructional shifts in writing” that ask teachers to do more “writing to text” – giving students content to read and then write about in a synthesis essay.

This kind of writing can be taught well, especially if students are allowed, as the standards suggest, to do their own research projects of various lengths. But what I hear from my students is that the only writing being taught is the kind Lily describes in the strip above.

Most students tell me that they are seldom allowed to write in any other mode. I suspect many, if not most, of their teachers would like to allow students to write in other modes, but school systems often demand a laser-like focus on standardized tests, which often demand the “writing to text” essay.

Students should be writing in multiple modes and genres; even the Common Core standards ask for narrative writing. But I’d like to set the issue of writing modes aside for a moment and look at a writing skill even more basic than choosing a genre to write in: having something to write about.

Adolescent life – that’s a built-in prompt!

This narrow approach to writing instruction has a long history. More than a decade ago, I wrote in my book Writing Extraordinary Essays: Every Middle Schooler Can! (Scholastic, 2008) that we were “prompting our students to death.” We – or the text book publisher or district or whoever – comes up with a prompt and focus for students to make their writing easy to score.

But one of the chief tasks of writing is choosing a topic, and we seldom allow students to choose. Many of our students suffer from the illusion they have nothing to write about – an illusion encouraged by a system that almost never permits them to find their own topics.

Early in my career – before my state of Florida even had standards or standardized tests! – I struggled to convince my reluctant writers that they did indeed have things to write about. I was re-reading Ray Bradbury’s Zen and the Art of Writing at the time, and in his essay “The Joy of Writing” I stumbled across his idea that writers write about what they love and what they hate. Powerful writing gets its power from the enthusiasms and frustrations of the writer.

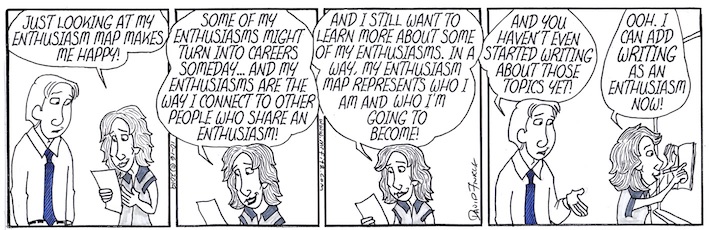

Armed with this idea, I borrowed from the master and created two of my favorite, most useful teaching ideas ever: the Enthusiasm Map and the Frustration Map.

These twin ideas are very simple, and almost every student is willing to give them a try.

Enthusiasm maps. Some students, it turns out, have a very limited supply of enthusiasms – at least enthusiasms they are willing to share. But even that lack of enthusiasm is valuable information about that student. Many other students, once they get going, will have a lot to put on their maps.

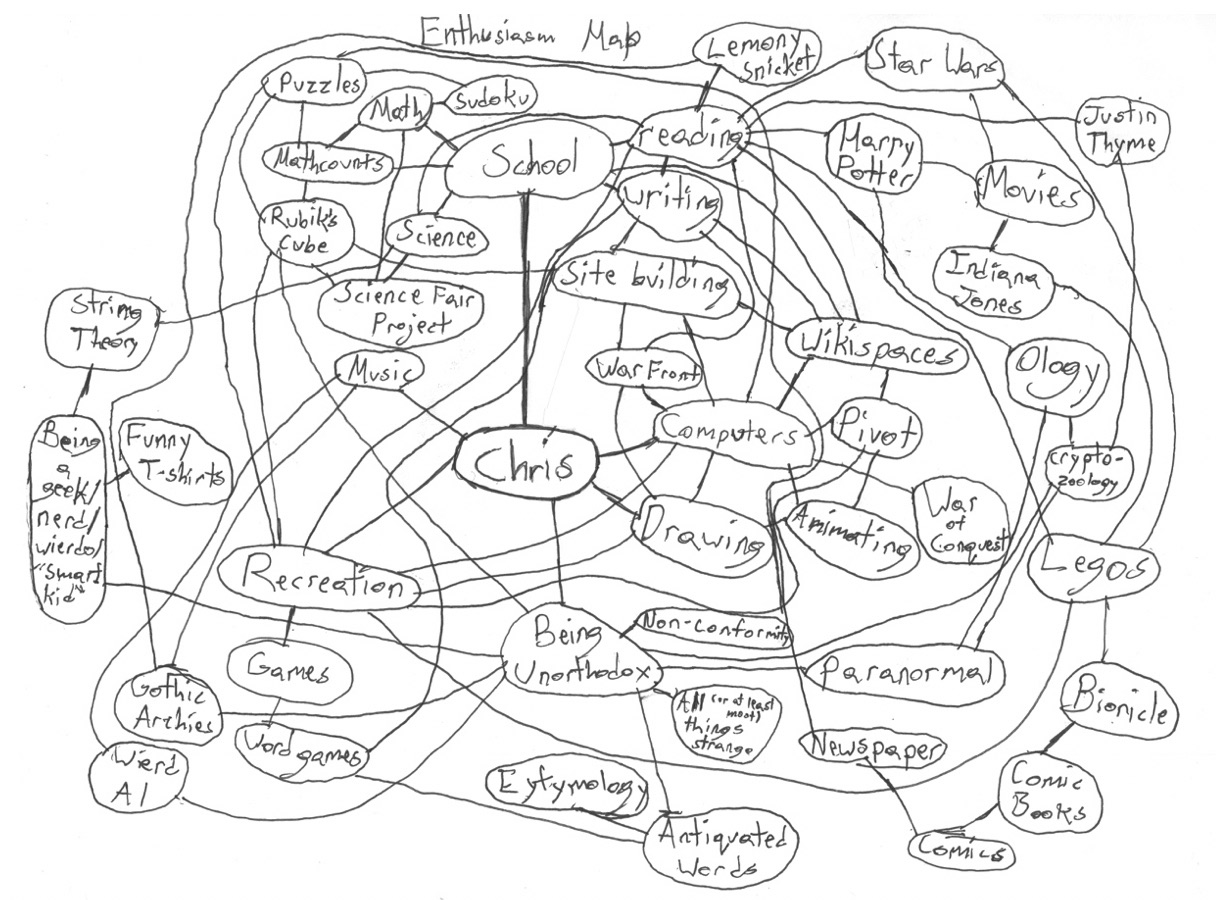

The map below is my own son’s map from when he had me for 7th grade Language Arts. He is now in his twenties and has added and subtracted some items, but a high level of enthusiasm remains. Knowing what your students are enthused about gives you a point of reference to relate to them better.

Frustration Maps are easier for some students and more difficult for others. Lily Tomlin is quoted as saying that “Language evolved out of man’s deep inner need to complain,” and some students seem to embody that idea. Coming up with frustrations is no problem for them – even if they sometimes choose to complain about your class…

Other frustrations touch on real issues the students are dealing with, and since I’ve given them the freedom to express themselves here, I let them vent.

I have at least a couple of students every year who tell me that nothing frustrates them. I don’t get frustrated myself – I take a “wait and see” approach.

The Worry and Wonder maps

The Enthusiasm and Frustration Maps have served me well for many years. There have been times with I “looped” with classes and taught the same students for up to three years. With so many familiar faces, I wanted new sources for student writing topics.

The concept is popular in both psychological and artistic circles – Disney/Pixar’s movie Inside-Out is probably the best known take on the concept. What struck me is that I had two of the basic emotions covered – joy and anger (enthusiasm and frustration), but I hadn’t touched on the others.

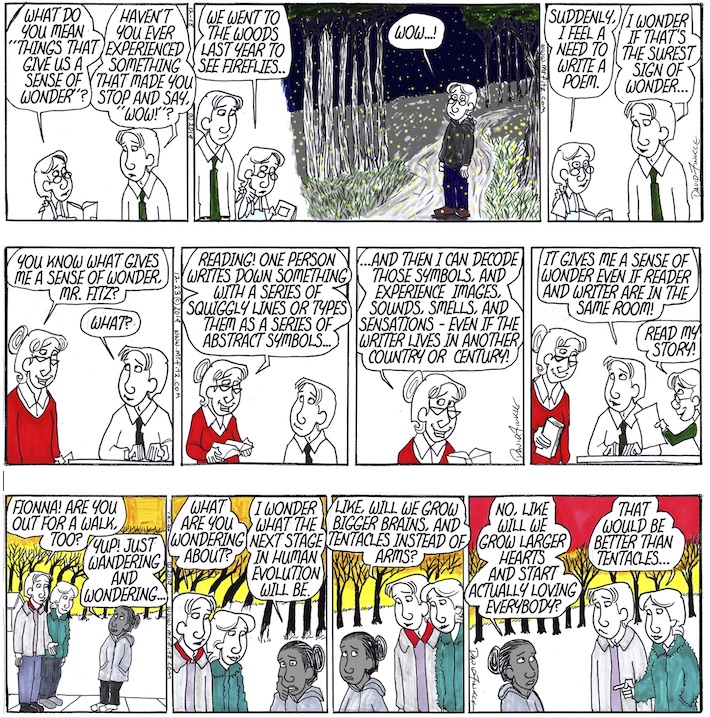

A surprise map seemed unlikely, and a sadness map seemed – a bit sadistic. I wasn’t quite ready for an entire class of students weeping over their composition notebooks. But worry and fear might work together… and then another strong sense of emotion struck me: Wonder. So I added two more maps.

The Worry Map

The Worry Map can be touchy. I tell students that I know that it is very personal, and that if they don’t want me to read it, they can write “DON’T READ!” in very large letters across the top of the page, and I won’t read it – I will simply check to see that they attempted it.

What kind of writing could come from a Worry Map? Having done these maps with students for a few years now, I can tell you that an awful lot of speculative science fiction comes from authors’ worries: can’t you almost see the worry maps that George Orwell, Ray Bradbury, Aldous Huxley, and Lois Lowry had in their heads as they wrote 1984, Fahrenheit 451, Brave New World, and The Giver. A Worry Map also gives you a lot to argue about in a persuasive essay.

But of course, there is one genre many of our students are enthusiastic about that is almost always based on worries…

I have even based some comic strips on my own worries…

The Wonder Map

The last map I currently do with students is my favorite of all – the Wonder Map. If there is one thing I think we need more of in schools, it’s things to wonder about, and things that give us a sense of wonder. So those are the things a Wonder Map asks students to ponder.

… or quite non-trivial…

Doing a Wonder Map sometimes helps my “A” students get over the idea that they get good grades so they “know” everything.

As for what gives students a sense of wonder, their ideas may astound you. When I introduce the Wonder Map, I ask them, “How many of you know that you think really big thoughts a lot of the time, but no adult would take them seriously?” Generally speaking, every hand in the room goes up.

My students write about the night time sky, about pondering who made God, about watching a sunset and imagining the earth rotating away from the sun. Some of them don’t know what I mean when I say “a sense of wonder.” Talking to their classmates about their Wonder Maps might be the thing that opens their minds to having a sense of wonder for the first time.

What can we do with maps and topics?

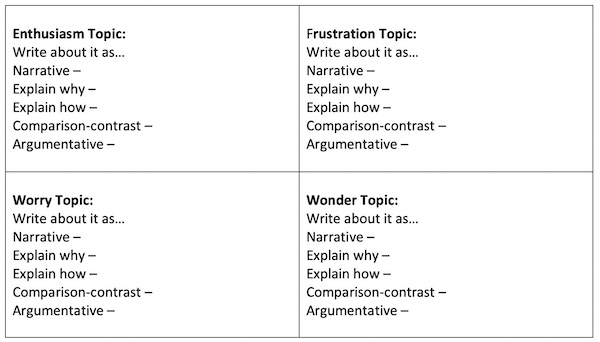

I often follow up on the maps by having students create a grid like this one:

I ask students to choose one topic from each of their maps – a topic they know they could write about – and brainstorm five different ways to write about it. I tell them, for instance that if I choose cartooning as my Enthusiasm Topic, I could write about it the following ways:

- Narrative – Write about how I developed my love for cartooning as a kid and about my first cartooning studio – established in the Christmas decorations closet when I was 8.

- Explain why – Explain why Peanuts was one of the best comic strips ever drawn. (I actually wrote this piece for the Orlando Sentinel when Charles Schulz died.)

- Explain how – Explain the process of creating a strip, from idea to turning it in to the newspaper.

- Comparison-contrast – Compare two of my favorite comic strips: Peanuts and Calvin and Hobbes.

- Argumentative – Argue that hand-drawn animation should remain a viable art form in an age of 3D computer animation. (I have also written this piece for the Sentinel.)

If students can fill out even part of the chart, they will have learned something about playing with topic and genre, but they will also have several viable essay ideas they can begin to develop. If they fill out the entire chart, they will have 20 viable essay ideas.

Taking the possibilities further, if they have 10 ideas per map, and five ways to write about each of those ideas, they have 200 potential essays. If they have 20 ideas per map, they now have 400 essay ideas! So much for “I don’t have anything to write about.”

Ideas. Engagement. Self-knowledge!

This is about more than having ideas. Students will learn to write better if they are engaged in their own writing, and most students will be more engaged by their own enthusiasms, frustrations, worries, and wonders than they will be by answering a prompt after reading three essays about tofu.

The value of these maps goes beyond engagement. The maps help students get to know themselves better – an essential part of the social emotional learning that has become so important in schools. The maps also help them chart a course into the future. I have seen students become aware of their passions and turn something from their enthusiasm map into a career.

Yes, we may have to give them practices for the writing test, but why not let them practice their writing skills by finding something they are actually interested in to write about? Why not set them free to find their own topics? It can make all the difference in their engagement, their writing, and their lives.

He is the author of two professional books for Scholastic, and for 20 years has been drawing Mr. Fitz, his wonderful comic strip about teaching, online and for local newspapers (become a Patreon supporter here). This post draws on Writing Extraordinary Essays: Every Middle Schooler Can! (Scholastic, 2008) with the addition of a dozen more years of teacher wisdom.