Celebrate Poetry Month with 5 Fun Activities

By Marilyn Pryle

April is National Poetry Month, and to celebrate, here are five fun poetry activities students can try. Each of these is not only skills-based, but creative and meaningful.

April is National Poetry Month, and to celebrate, here are five fun poetry activities students can try. Each of these is not only skills-based, but creative and meaningful.

The first two work best as individual assignments, the third and fourth can be done either alone or in partners, and the last is a fun whole-class activity.

(If you’d like to see additional poetry activities I’ve written about on MiddleWeb, try the Concrete Found Poem or the Personal Ballad.) Enjoy!

1. Me in Metaphors

This descriptive poetry-writing activity asks students to think of personality traits and talents and translate those into metaphors. You could do a mini-lesson about metaphors if you’d like, but students will pick up on the idea pretty quickly.

Students should think of eight qualities about themselves (these could be physical, emotional, mental, and so on) or talents that they have. They should list these on this prewriting sheet. Then, students should think of an image (a sight, sound, smell, taste, or texture) that could represent each quality.

For example, if the quality is calm, then an image representing calmness could be stones at the bottom of a river. Encourage students to then expand the image to make it more interesting and descriptive – “stones at the bottom of a river” could become grey, white, and speckled stones lying below the rushing river waters. Students should do these for each of their eight qualities.

To write the poem, students simply list all the metaphors in a row, beginning with “I am…” They should not name the qualities themselves; they should let the metaphors do the work. Here are two examples of students’ finished poems:

Me

by Hayley

I am a thin branch, shaking in the wind.

I am a small pond rippling rapidly in the new spring air.

I am a sun-burned shoulder, tender to the touch.

I am a leaf torn in a storm.

I am a tiny blue flower budding in snow.

I am a stone smoothed by rough, rushing waters.

I am the first bike in the garage without training wheels.

I am a beam of light shining through deep waters.

Me

by Seth

I am a tree towering over a thriving forest.

I am a gracious gazelle prancing through the desert.

I am a bottle filled to the precise amount for flipping.

I am the “Enter” key on a calculator.

I am the single brush stroke against the grain.

I am the feeling of peeling plastic off a new cellular device.

I am the smell of abundant bacon begging to be bitten.

I am the fast crack of a thick whip.

As you can see, it’s not important for the reader to guess the “right” personality traits; that’s not how poetry works. Instead, students will create an impression of themselves, a feeling rooted in sensory details, that somehow holds more truth than a spelled-out list of traits.

2. Ode

Odes are free-verse poems praising something, and they can be about anything—an object, a place, or even a person. What makes an ode powerful is an attention to sensory detail.

I love to use Gary Soto’s Ode to Mi Gato as an example – it is full of everyday sights, sounds, and textures. All odes, by definition, have the same theme: an appreciation for their subject; Soto’s love for his cat shines through in the details.

Writing an ode is an especially important exercise for students during this difficult year. The practice of looking closely at something – especially some everyday object perhaps taken for granted – and feeling gratitude and appreciation for it, can be powerful and healing.

Once students choose a subject for their ode, they should brainstorm sensory details, and work in the figurative language as they go. Here’s a brainstorming sheet.

For more examples, look to Pablo Neruda’s many odes, especially “Ode to My Socks,” or additional poems from Soto’s Neighborhood Odes (2005).

3. Extended Metaphor Poem

For this activity, I like to use Langston Hughes’s “Mother to Son” as a mentor text. The main metaphor is actually a non-metaphor (“Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair”), but students can make inferences about what the converse meaning would be – something like “Life has been an old, beat-up, dangerous stair.” After reading, have students map out the “extensions” of the main metaphor.

This can be done with a mindmap or even a labeled drawing of the stairs themselves. The extended metaphoric details in Hughes’ poem would include tacks, splinters, torn boards, and worn-through carpet. They would also include landings, corners, and some darkness. All of these are symbolic, of course, and can be discussed or even incorporated into the students’ diagrams, perhaps in a different color writing alongside the literal extensions.

The mother’s advice (“Don’t you sit down” and “Don’t you fall now”) is symbolic, thematic, and an extension of the original metaphor as well.

Another effective mentor text is Rumi’s The Guest House. The original metaphor is that being human is a guest house – an old-fashioned inn. The extensions are that the guests are one’s emotions, and that the house includes furniture and a door. The metaphor is carried through to the end of the poem. Students could create a diagram of a house to illustrate the literal and deeper meanings.

Once students understand the idea of an extended metaphor, they can try their own. This activity works particularly well in pairs. Students should start with a basic metaphor, and then list some “extensions.” They can do this by picturing or drawing the original metaphoric image, and then studying the details for ideas of how to make it more symbolic.

Some original metaphors might be:

Friendship is a…

Learning is a…

High school is a …

The football field is a…

The stage is a …

Being a preteen (or teen) is a…

In my class, I ban “Life is a highway” since that is so well-known. (You could, of course, use the song as an example!) Additionally, you might want to avoid “Life is a rollercoaster” if you don’t want to read several of them.

I ask students to have at least three extensions to the original metaphor, sensory details with each extension, and a minimum of twelve lines overall. After working with extended metaphors from the inside-out, students will never miss them in texts again!

4. Google Autocomplete Found Poems

Found poetry is a fun way to explore the question, “What makes a poem?” And a fertile place to look for poems is the Google search bar. In this time of virtual learning, many students have access to this tool.

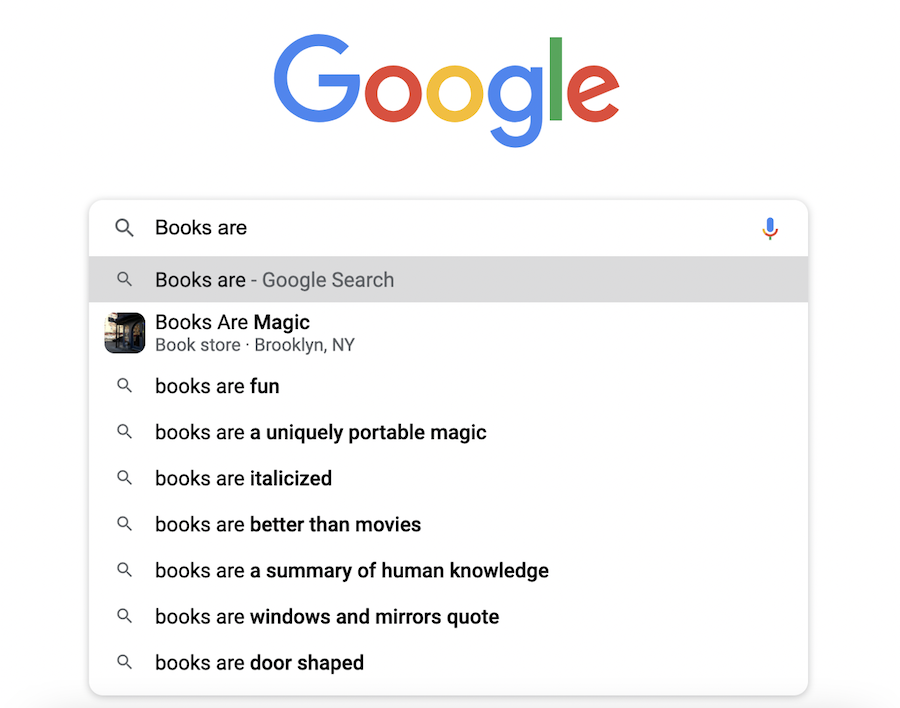

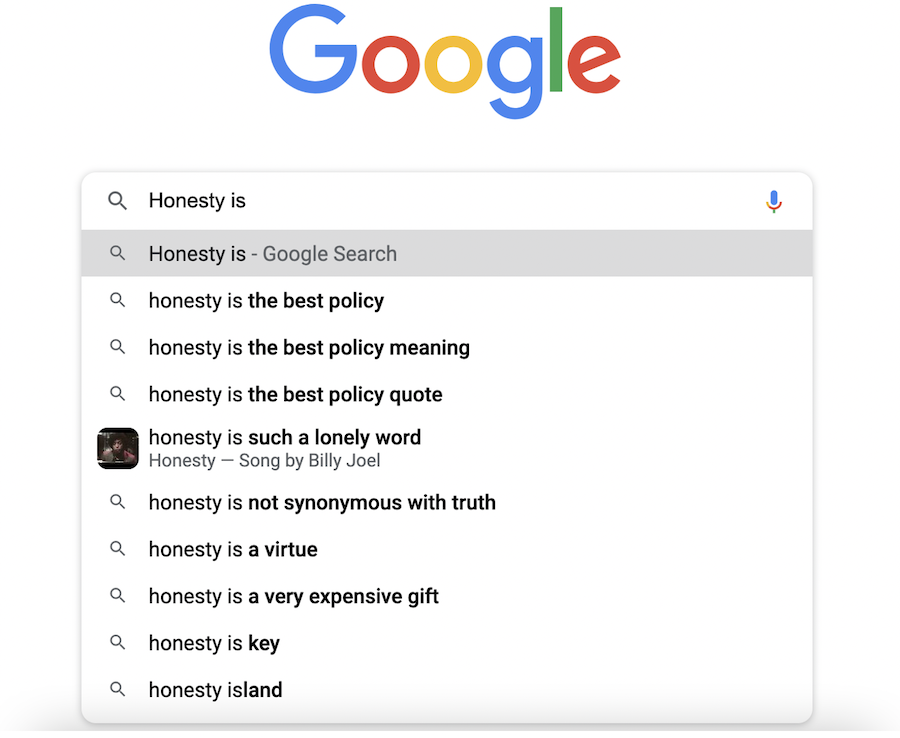

Students can think of basic ideas or sentences starters, such as “Books are…” or “Honesty is…” What comes up is the most searched-for endings to the thought – the coded wisdom of Google autocomplete. The above searches come up as such:

I encourage students to choose and rearrange what they find, so that it forms a poem to their liking. Of the searches above, final poems might be:

Books are fun.

Books are a summary of human knowledge.

Books are better than movies.

Books are a uniquely portable magic.

Books are door shaped.

——

Honesty is the best policy.

Honesty is a virtue.

Honesty is a very expensive gift.

Honesty is not synonymous with truth.

I usually set guidelines at a minimum of four lines, and let students work in pairs. You could instruct students to relate their Google searches to a book or unit’s theme in your class, to a certain character trait, or to an essential question. Or you could let students experiment with searches of their choosing.

Letting students play with the search stems and the phrases they find provokes thought and creativity. Adding a word to the search, or even a single letter, changes the trajectory of the results.

At the same time, what comes up in a Google search is also a barometer of society – the autocomplete suggestions are the most-searched-for ideas; this is what puts them on the list. Students’ findings could provide grounds for interesting class discussions.

5. Haiku Party

Haiku Party Day is, by far, the most fun day in my class. We study haiku in depth during the days leading up to it, including the terms caesura (the pause) and kigo (a seasonal word), and the use of a twist – the surprise or shift in perspective that comes at the end of a haiku.

Waves of summer grass:

All that remains of soldiers’

Impossible dreams.

My favorite haikus to teach include Basho’s “Summer grasses,” “The cuckoo,” and “The sun’s way,” as well as Issa’s “Far-off mountain peaks” and “With bland serenity.” These haikus all have a palpable surprise that the students enjoy experiencing. We go deeper than the 5–7–5 rule, although that parameter is important and fun too.

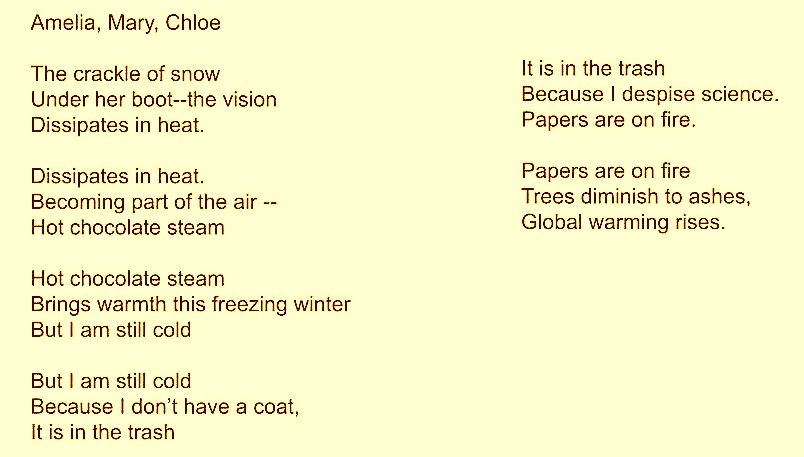

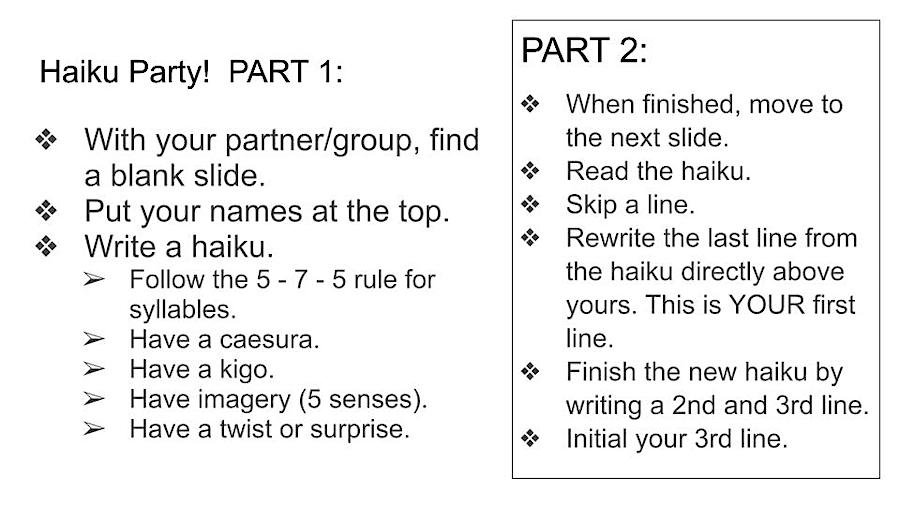

To conduct a Haiku Party, have students partner up and give each pair a blank piece of paper (this year, we did the activity on Google slides, with each pair’s work on their own slide, in a larger class slide presentation).

The pairs should write one haiku at the top of the page. You can set as many guidelines for this as you’d like – I require students to have a 5-7-5 format, as well as a caesura, kigo, and twist, since that’s what we study. This part might take a few minutes if students have never written haikus before.

They should read the other group’s haiku, skip a line on the page, and then rewrite the haiku’s last line. This is now their first new line. The group should finish the new haiku with a second line of 7 syllables and a final line of 5 syllables.

You will have to explain this a couple times for students to understand. They take the previous group’s last line, rewrite it on a new line, and use it as a first line for a new haiku.

When finished, the papers get passed again (following the same path) and the process is repeated. Fit in as many rounds of this as time allows. The class will quickly devolve into hilarity as students frantically count out syllables on their fingers, trying to finish the haiku formed from the last line of the most recent poem passed to them.

At the end, students can retrieve their original pages and read the haiku chain born from those first three lines. They love it.

I’ve witnessed students literally weeping with laughter during this activity. But while it’s happening, they’re practicing skills – poetic form, sensory details, and the twist, at the very least! Students also get a taste of how texts and writing can be fun and alive.

And isn’t this the true purpose of teaching poetry, and all literature: to give students that sense of connection, collaboration, and creativity as they express themselves and read the expressions of others?

Marilyn’s most recent book is Reading with Presence: Crafting Meaningful, Evidenced-Based Reading Responses (Heinemann, 2018). Learn more about her at marilynpryle.com and read other articles she’s written for MiddleWeb.