My Long, Winding Road to Better Homework

Back in 2011, I was a new fourth grade teacher. I knew that I was supposed to give students homework because that’s just what we do in education.

So I dutifully made copies of the math homework assignment sheets, sent them home each day, put a star on the ones that were returned, marked it off in my grade book, and hopefully remembered to send back the completed homework so that parents could see the stars.

I didn’t grade it because my cooperating teachers had done a great job of teaching me that practice work should never be graded. Some students did the homework every single day. Most did most of it. Some never did a single assignment.

Jump ahead a few more years.

I was now a veteran fourth grade teacher and I got a call from a parent one morning: “I’m so sorry my student didn’t finish his homework last night! I made him sit at the kitchen table and made him work on it all night, but after three and a half hours, he was in tears, I was in tears, and I decided it just wasn’t worth it. I’ll make him finish it tonight, I promise!”

I was stunned.

Three and a half hours?! Our school homework policy was printed in the parent handbook and clearly stated that we used the ten-minute rule: a student takes their grade in school and multiplies by ten and that is the amount of time homework should take. For a fourth grader, that meant 20-25 minutes of independent reading and 15-20 minutes of math practice. Not 210 minutes of math!

This was all my fault and I knew it. I apologized to the parent and assured her that her child absolutely did not have to work on the assignment that night. I also told her that he should only work on it for 15 minutes and then just turn in whatever is completed. If she wanted to sign it, that was fine by me.

And thus began my quest for change.

I

That year I started by sending a letter home to families explaining the homework policy and telling them what I told that mother on the phone. We got through the end of the year, and it seemed like things were better.

That summer I stumbled upon some research done in the 1980s claiming that all of the so-called benefits of homework, especially in the elementary grades, were a sham. There was just no evidence to support it. I dug further and found more research supporting this. I found blogs from parents and teachers and principals. I found book titles and podcast episodes.

Everything told me the same thing: stop doing homework!

Well, unless it was reading. Students should absolutely be expected to read at home. But that’s was it. No math sheets, no papers to be written out of class, no last-minute research projects and shoebox dioramas to be completed by flustered parents the day the project was due.

And so I revolted. I started the year off and I told my students that the only homework I would give them all year was to read for 20-25 minutes each night. That was it. I sent a newsletter to parents and I told them the same thing. I wanted my students to reclaim childhood and play and not spend all of their non-school hours doing school.

I was happy. My students were happy. The parents… Well, some of them were not happy.

The parents who were not happy didn’t come to me, though; they went straight to my principal, which is why I got an email from my principal one day telling me that she needed to talk to me about some complaints from parents.

I found out that there was a sizeable portion of parents who were very upset that I was not doing homework. I explained my approach to my principal. She was sympathetic, but she told me that I had to give some sort of homework and it had to be entered into the gradebook to track completion. I told her I would start sending the math sheets again but also wanted to think about what else I could do.

And so the homework menu was born.

I honestly have no idea what triggered the idea or how it developed fully. I only have a vague notion of giving students options, letting them pick, but making sure that reading was a non-negotiable.

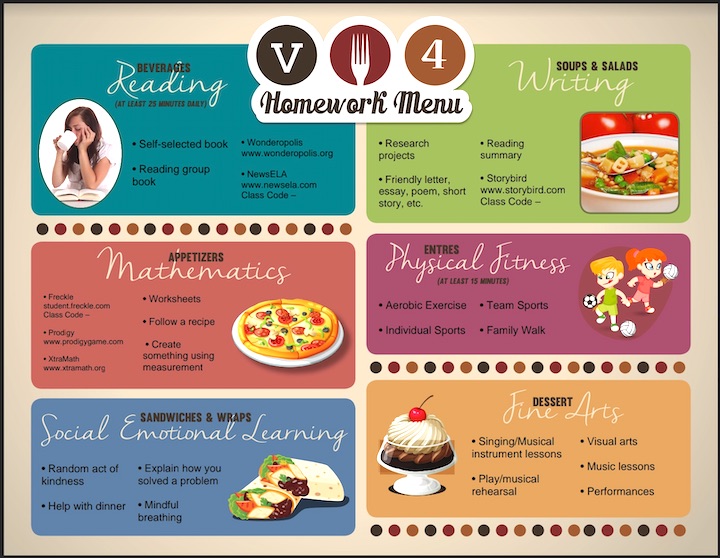

Somehow that led to the idea that sit-down restaurants always bring you a drink, even if it is just water. Reading is the beverage. Everything else is… well, everything else. Appetizers, entrees, soups and salads, sandwiches and wraps, desserts.

I talked to my wife about my idea because she is a graphic designer and I wanted her to turn my vague idea into something amazing. I talked to some of my colleagues and they helped me generate ideas. I talked to my students and they gave me more ideas. And then I got to work putting my homework menu into practice.

I sent a letter to parents, I explained the idea to my students, and I made sure my principal was aware of my plan. It was fairly straightforward: Each night, fourth graders were expected to spend up to 40 minutes on homework. Of that time, it was required that 15-20 minutes be spent on reading. The remaining 25-30 minutes were at the student’s discretion, although parents had veto power.

Some of the options included more reading, writing of any sort, math (including worksheets and websites), physical activity (including sports practice or family walks), or fine arts (music, visual, or performing arts). I sent a simple checklist home each Monday so students could record what they did and turn it in at the end of the week. (I later abandoned the checklist because it seemed silly.)

The results were exactly what I had hoped for.

Students were happy because they got to pick what they worked on. Parents were happy because they got to see what their students were learning, had a guide for what they should be doing, and were able to be more involved than they had been when there was no homework.

My principal was happy because the students and parents were happy. I was happy because I had been able to abandon something I viewed as a waste of time and found a way to get students more involved in their own learning.

This last part was what was most important to me. My mantra has long been that my job as an educator is to help students learn how they learn so that they can learn without anyone telling them what to learn. Or, to draw from one of my favorite quotes from Elbert Hubbard, “The object of teaching a child is to enable him [or her] to get along without his [or her] teacher.”

I started sharing this menu with others on social media and had many ask if I could make a version that they could adapt. I didn’t know how to do this but, fortunately, my wife did and so she worked her magic and turned my homework menu into something that can be easily adapted by others. For those who are interested, it can be accessed here.)

There is another side to this story, though.

The homework menu provides a framework for allowing students to use voice and choice in selecting homework, but what if there is homework that the teacher wants students to work on? Or what if the student attends classes taught by a team of teachers? Is it realistic for all of them to give a menu of options?

Is there a way to be more intentional, more D.E.L.I.B.E.R.A.T.E. in how we design and assign homework?

- Differentiation – How are we adapting to our learners’ needs?

- Explanation – Have we made our expectations clear?

- Learning – What do our students’ need to understand about the assignment?

- Implementation – How will we put changes into practice?

- Bolstering – What message needs to be amplified?

- Empowerment – How will student voice and choice be taken into account?

- Reflection – What is working, what isn’t, and what do we need to change?

- Asking – Who are the stakeholders whose feedback we should be seeking?

- Terminating – What should we stop doing?

- Entrusting – How will we demonstrate our trust in students to rise to the occasion?

Homework does not have to be a meaningless chore that students slog through in order to meet arbitrary standards of compliance. Homework does not need to be a source of frustration for students, families, and parents.

By giving choice and being DELIBERATE in our practices, homework can be an empowering tool for students to continue their learning outside of the classroom and to allow them to connect the work in the classroom to the world around them.