Scaffolds & Bridges: Reading & Writing about Nonfiction

By Alicia Genchi and Sunday Cummins

Alicia

It never fails.

With some students, you can have the best time analyzing and talking about an informational source, but when they go to write a short response, they lose their grounding and start to fall.

How do we help students bridge the gap between reading and writing? In our practice, making a plan for a written response is an essential scaffold for bridge building.

The Value of a Plan

Sunday

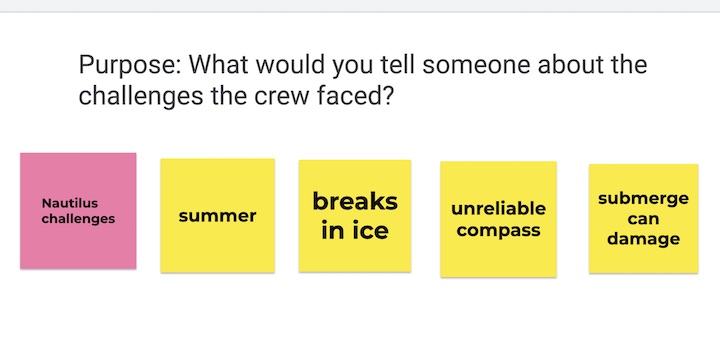

Recently, Alicia, a reading specialist, worked with a group of fourth grade students who read a short book (28 pp) titled Under the Ice (Feely, 2014) about the first submarine voyage below the Arctic ice pack. There’s a lot of information in this book for a reader to digest, but the students had a clear purpose for reading, stated as a question: What were challenges the crew of the Nautilus had to overcome?

There were rich, eye popping discussions about water pressure squeezing submarines to the collapsing point and the magnetic North Pole making compasses unreliable.

Now the students needed to write a short response about what they had learned. This is when many students get overwhelmed.

How do they share all they learned? And looking back at their annotations, how do they make sense of so many notes? This is where planning for a written response can be invaluable.

A plan identifies the key details from the source or their annotations that a student wants to include in their response. This can be a few sticky notes with key words or phrases written on them or an abbreviated outline.

When planning, the students choose simple words and phrases that serve as triggers for what they need to remember to share when writing. If they need more information, they can always look back at their annotated sources for that additional information.

Model Creating a Plan with Visuals as Support

Creating a helpful plan is not always easy. Students have to look at annotated sources or notes and determine what’s important. They also have to figure out how to organize that information so their response is cohesive. Modeling for students how to do this is essential. This includes thinking aloud about the following:

- What’s my purpose for writing?

- What did I learn that helps me think about my purpose (from this part of the source – as revealed in my annotations)?

- How do I decide what’s important to include when I write?

- What do I need to write in my plan to help me remember this?

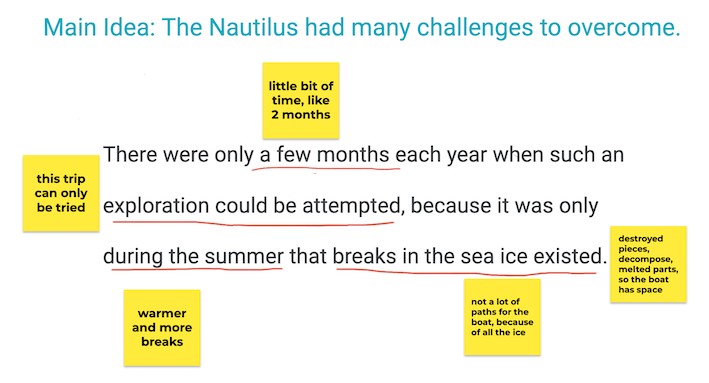

Alicia taught these lessons on a virtual platform during the COVID-19 pandemic when school buildings in her district were closed. For the lesson on creating a plan, she started by screen sharing a Google Jamboard with one of the excerpts from Under the Ice the group had annotated.

There’s a lot of information I need to think about right here. I need to start by remembering that I’m writing about the challenges the Nautilus faced. And the challenge revealed in this excerpt is that there was only a little bit of time (which I wrote in my annotation here) each year in which they could make this trip. That was in the summer.

I think before I share any other details from what I learned, I’m going to write down *summer* on a sticky note as the first part of my plan. That’s what I’ll write about first. [Alicia flips to a new slide in the Jamboard and types “summer” on a sticky note.] Now I need to go back and review my annotations again to think about what I want to include next. Anybody want to help me?

The image below is of the finished plan (based on the group’s review of two annotated excerpts). In a follow-up lesson, when students began to write a plan for a written response on their own, Alicia reinforced the process they had experienced together. She inserted the Jamboard slides of the annotated excerpts and the plan into a Google slides presentation for students to reference. She posted reminders on the slides like:

- Remember to read your annotations.

- Think about key words that you might want to include in your plan.

- Write the key words on sticky notes!

Key Words or Phrases Only, Avoid Sentences

Key Words or Phrases Only, Avoid Sentences

Notice there are not an abundance of details in the plan the students created with Alicia. If students include too many details, they may get overwhelmed with making sense of how to put the details into writing. Encourage students to choose key details that trigger a memory of what the student learned or that trigger just enough recall for the student to remember where to return to her notes for more information.

You’ll also notice that there are not any sentences. If students include sentences in their plans, they may be tempted to copy from a source. They may spend a lot of energy writing that sentence and may only want to copy it into their finished piece as well. This is problematic if they need to think about how to combine two or more details that are in their plan.

The key words or phrases are also in a particular order. Ideally, the order helps the students build or develop their ideas in their written response.

Return to the Plan Again and Again

Students may write from the plan you created together – or they may write from a plan they created on their own. You can even start a plan together and then have them finish on their own. Regardless, as they engage in writing a response, they need to return to that plan again and again.

When they finish developing an idea, then they need to return to the plan to look at the next sticky note. You can support this during writing conferences by reminding them to return to the plan.

Hopefully, over time, students will engage in this process of moving from reading to writing on their own. In the meantime, modeling how to write a plan for or with students, thinking aloud about how you decide what to put in a plan, creating anchor charts, and conferring with students can be powerful scaffolds for supporting them as they build the bridge.

Alicia Genchi is an intervention specialist at Terrell Elementary, part of San Jose (CA) Unified School District. She is a graduate of Santa Clara University and holds a master’s degree in Instructional Technology. She currently provides guided reading and writing instruction to students in grades K-5.

Sunday is the author of several professional books, including her latest releases, Close Reading of Informational Sources (Guilford, 2019), and Nurturing Informed Thinking (Heinemann, 2018). Visit her website and read her regular blog posts on teaching information literacy. Follow her on Twitter @SundayCummins.