Giving Our Students the Key to the School

We empower students when we engage them in their own assessment.

I grew up in a very small town in southern Manitoba, and unless you owned a snowmobile, all you could do on a blustery Sunday afternoon was read, sleep or stare at a pixilated rendition of PacMan through an Atari 2600 console. (Some of you may need to look up ‘Atari 2600’ on Google.)

Limited options and sheer boredom prompted us to pester our school principal for a favor. A few of us loved to play volleyball, and if we could coax Mr. Koop to unlock the doors to the school gym, we had all afternoon to play.

Although he never complained, it didn’t take a psychologist to realize he wasn’t exactly delighted to have his restful Sunday afternoon interrupted by an icy ride over to school. On one of these particularly cold occasions, as we were shoveling our way through the snow to reach the school entrance, Mr. Koop said to me, ‘Myron, drop by my office tomorrow – I have something for you.’

On Monday I arrived at his office before school started, curious as to what he meant. ‘That’s for you,’ he declared, pointing at a single key laying on the corner of his desk. ‘It’s a key to the school so you don’t have to call me to open the gym anymore.’ While I was delighted at the prospect of unfettered weekend access to the gym, I was probably more surprised, stunned, and perhaps honored. He finished by saying with a smile ‘I probably shouldn’t do this, so don’t make me regret it.’

It’s been 30 years, and I’m sure it’s outdated, but I still have that key. My school friends joked a few times about using it to explore the building, or get into a classroom, but ‘all the tea in China’ would not have coaxed me to betray Mr. Koop’s trust. It wasn’t lost on that 17-year-old version of me that the principal was making a statement – he was sharing the ‘key to the castle.’

Mr. Koop influenced me to enter his profession – to be an educator. Now I’m a school administrator, teacher and author. Although I have not gifted any school keys to my students, I am trying to help students unlock the door to assessment – personally and meaningfully, with full ownership.

The Elevator Pitch

In my latest book, Giving Students a Say – Smarter Assessment Practices to Empower and Engage, I discuss the importance of developing an elevator pitch – ‘the succinct encapsulation of an idea that takes no more than 20 seconds to convey’ (Dueck, p 5, 2021).

Whatever our cause or purpose, it’s important to have it distilled, easily understood, with the veils removed. This pitch can then act as a rudder or guide when making decisions, talking to any stakeholder or hatching a new plan. I describe in the book a staff activity that any school could tackle. Simply have staff members construct a response to this question:

‘Why would someone want to attend ________ (your school)?’

This soul-searching exercise allows staff to internalize just what the essence of their school is or should be. If you want to conduct this activity with your team or department, all you need is a set of recipe or index cards, and an envelope for each faculty member.

Give people 10 minutes or so to come up with their initial answer, put it in an envelope adorned with their name, and redistribute them at the next meeting or some later date to reflect, change, rewrite. When we tried this at Summerland Secondary, by the end of the year everyone had a personal elevator pitch for the school. Here are three:

“SSS helps to build students’ skills and confidence so that they can be successful in whatever path they choose.”

“We are small enough and big enough to create amazing opportunities for our students and staff. Our opportunities reflect modern realities and valued traditions to balance all areas of learning and to prepare our students for challenges known and unknown.”

“Small, Supportive, Innovative, Creative, Flexible . . . Like Cheers, where everybody knows your name.”

Speaking of an elevator pitch, my version for assessment kind of relates to Mr. Koop and the key to the school.

In every aspect of assessment, we will engage and empower the student by offering opportunities for student voice, choice, self-assessment, and self-reporting.

With this pitch acting as a sort of rudder to my decision-making, it allows me to look at every aspect of assessment as an opportunity for student voice, involvement and ownership – a chance to let them in. Here are a few examples.

✻ Co-created unit plans

Clearly, I’m not the only one looking at how we can increase student agency, voice and empowerment. The OECD considers seven key principles when designing effective learning environments, and they too relate to giving students a key to the school.

Some elements include recognizing students as the core participants (Principle 1); that students are individually diverse and holders of prior knowledge (Principle 4); and that the learning environment should operate with clear expectations (Principle 6) (OECD, 2017).

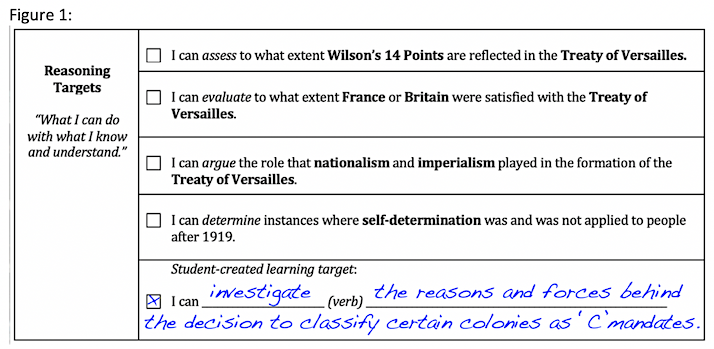

Considering my elevator pitch and the OECD principles, I’ve added a new feature to my student-friendly unit plans. Students have specific interests and often uncover new learnings within a given unit or area of study, so I’ve added space for students to construct their own learning objectives.

As you can see in Figure 1, students can decide on a verb and the content (noun) they wish to explore. This example was from a student fascinated by the secret Class C Mandate decisions at the Paris Peace Conference (1919-20).

When designing co-created unit plans, benefits for students include:

- Recognizing the importance of cognitive levels and curricular content.

- Exploring personal topics of interest within a domain of study.

- Engaging with, and understanding the value of, the unit plan .

For many examples of unit plans and other useful tools, visit my website.

✻ Born of constraint – Student self-reporting at term’s end

Shortly after I agreed to return to Summerland Secondary for the 2020-2021 school year, the principal asked if I would help co-teach the weekly leadership class – during COVID. I thought he was kidding. He wasn’t.

The next thing you know, we’re meeting every Thursday morning with a class of 35 students, in a theatre, separated by empty chairs, with many students (and one vice-principal with initials MD) wondering aloud – ‘how are we supposed to run school leadership events during COVID?’

Great question.

Well, I’m forever indebted to business consultants Mark Barden and Adam Morgan for supplying me with a curriculum. Their book, A Beautiful Constraint, helped our class reframe limitations and restrictions to push the boundaries on what was possible. Emboldened by the notion that constraints can actually make things better (Barden & Morgan, 2015), our class went on to collect more food in our annual food drive than all five previous years combined!

I shared our experience with Barden and Morgan, and they in turn shared our experience with 165 KFC franchisees. High school students helping coach the fast-food industry…it’s been a weird year indeed!

As our term was coming to an end, I was faced with writing reports for students who were engaged in activities that I could not always supervise. I decided to replicate the example found on page 150 in Giving Students A Say entitled, ‘What is My Grade?’

Students were given the opportunity to self-report on a number of elements from our course, describing what events they had been a part of and what they had learned as a result. Taking advice from John Hattie, I also asked students to consider what next steps they needed to take on their learning.

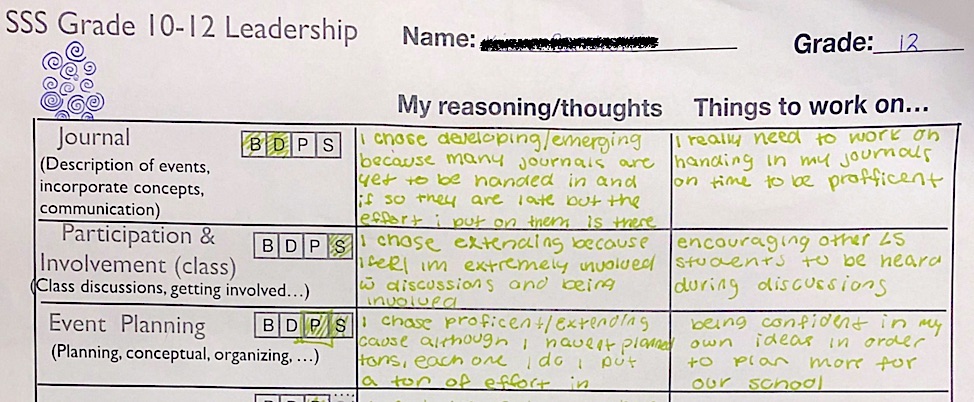

I read all of the student self-reports and had a handful of follow-up conversations if I needed more information. I then sat down to write report card comments using the student self-reports as a valuable perspective or guide. For a better idea of what this looked like, see the figure below. The letters in the small boxes stand for (B) Beginning, (D) Developing, (P) Proficient and (E) Extending.

Incorporating student voice into the report card process was not only a critical step to increasing student agency, but it made the process far easier for me.

✻ ‘Reporting my own effort’ – A logical step in student self-reporting

While I was in the initial stages of writing the draft for Giving Students A Say, I had the opportunity of interviewing a grade 12 student in our school named Xavier. He had been in my class in grade 10, and he was included in a series of interviews we were conducting around student self-reporting.

Shortly into the interview, Xavier recalled an instance in his ninth grade year, when he believed he was putting in lots of effort, only to receive an ‘N’ on his report card suggesting his effort level ‘Needs Improvement’. I was stunned while listening to him by how readily he recalled this reporting moment that occurred four years earlier.

I came in for help after school, I even came in for help at lunch and stuff like that. I remember not getting a great mark in that class – I think it was a 50 something, but it was that ‘N’ that I thought was kind of unfair. Like the teacher never asked me my part, like why I was not doing well, or why she figured I wasn’t putting in full effort.

After I stopped the camera, he looked over at me with a puzzled expression and added,

When it comes to reporting my effort, why don’t they ask me?

Xavier asked a really good question, and I knew I needed to finish writing Giving Students a Say.

We’ve taken Xavier’s advice and have started building reporting tools that give students the opportunity to weigh in on things they are in the best position to report. The book features a template by science teacher Ben Arcuri who asks his students to report on their personal responsibility, self-regulation, collaboration and social responsibility.

I refer to a grade 8 teacher, Barry Morhart, who gets students to write their own version of the effort and participation comments for their own report card, and he sometimes uses their words to convey to parents what he cannot necessarily say, such as one boy who wrote, ‘I tend to goof around in class a little too much’.

Giving students access to our world

We can place trust in our students that their voice matters in conveying their level of understanding and the level of effort they exert. And finally, we can empower students to self-report as a life-long skill.

Oh, and by the way, I looked up Mr. Koop recently and thanked him for the key, and I let him know just how powerful a role he played in my journey.

References

Barden, M. & Morgan, A. (2015). A beautiful constraint – How to transform your limitations into advantages and why it’s everyone’s business. New York: Wiley.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). The OECD Handbook for innovative learning environments. Available here.

Myron is the author of the best-selling ASCD book Grading Smarter, Not Harder (2014) and a new book, Giving Students a Say: Smarter Assessment Practices to Empower and Engage (ASCD, 2021, with a foreword by John Hattie). Learn more about his work with other schools and organizations at his website, and follow him on Twitter @myrondueck.