It’s Time to Reimagine Reading Comprehension

By Nancy Boyles, Ed.D.

Cobwebs have had many months to accumulate in the minds of our readers following a year that has been anything but ordinary.

Cobwebs have had many months to accumulate in the minds of our readers following a year that has been anything but ordinary.

In March 2020, Covid sent students fleeing from their classrooms, and educators scrambling for curriculum that could work well enough at home virtually, in a hybrid model, or six feet apart when students had the opportunity for in-person learning.

Understandably, the need for emotional well-being often eclipsed attention to academic rigor. But now, at long last, we can imagine a time when teachers and full classes of students can once again come together in the same room – and even enjoy the smiles on each other’s faces.

In fact, as we brush off the cobwebs and fill in the gaps created by this past year, let’s do more than imagine business-as-usual. Let’s reimagine teaching to accelerate learning in the most effective way possible.

Let’s begin with what that might look like for reading comprehension, thinking first about tasks that call for deep thinking based on priority standards, and next about instructional strategies that support comprehension of complex text.

Both components are explored in my new book, Writing Awesome Answers to Comprehension Questions (Even the Hard Ones). Offered here are highlights to get you started.

Choose tasks that call for deep thinking based on priority standards

How do we know when we have a suitably challenging task? It may require analysis, an inference, integration of ideas, or a combination of various thinking processes.

Asking for text evidence or details, while a prerequisite for deep thinking, is not itself a deep-thinking task; students must use those details to problem solve or develop their own interpretation.

For example, after reading a mystery you could ask students: Which details were the most helpful in solving the mystery? After reading a nonfiction selection, you might ask: Which details were the most surprising?

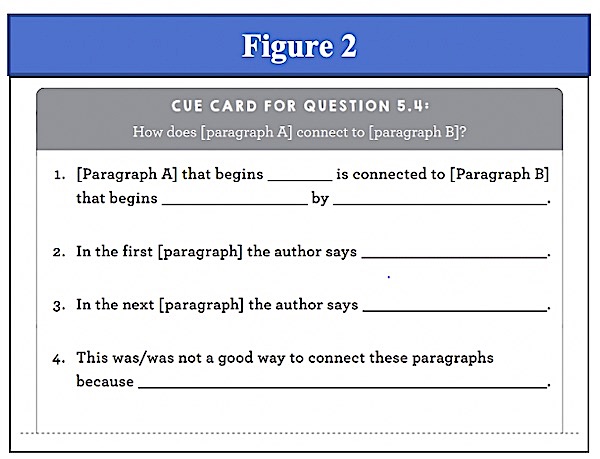

Some other questions that call for deeper thinking include: What is the relationship between [Character A] and [Character B]? Why do you think the author wrote this piece as a [poem]? How does [paragraph A] connect to [paragraph B]? Which source does a better job of explaining _____?

Note that these questions move beyond more common queries about character traits, text structures, and connections between texts. Rather than falling back on the same questions time after time, branch out. Recognize that new standards uncover dozens of new possibilities for literary exploration. But we need to refine our search.

First, determine priority tasks. As we peruse comprehension standards and the tasks they entail, they all seem important – especially after students missed so much over the past year. But we can’t scale this mountain in one leap.

Our students would be better served by choosing a few key tasks to get started. Also determine whether those tasks need a less complex concept as a starting point. For instance, asking students to identify the theme in one text should precede comparing themes across two or more texts.

A final thought about tasks is to make sure all students have the opportunity to respond to complex tasks based on complex texts. If we are serious about pursuing equity, we will offer everyone in our class equal access to grade-appropriate content – and the instructional strategies to make that content meaningful.

Use strategies that support comprehension by ALL kids

Back in the day, my primary means of supporting students’ responses to comprehension questions was through answer frames tailored to individual standards-based questions. Frames laid out the response in an organized fashion so readers could produce a coherent answer. At the time, this seemed like a great strategy. And it did work – for the kids who just needed help getting their thoughts down on paper in a way that made sense.

However, it did little for students with insufficient comprehension of the reading itself. It turns out that writing good answers to comprehension questions is more about reading than writing. So, how do we scaffold reading comprehension for students who can decode, but still don’t understand?

It’s not just one scaffold; it’s several. First, begin with the concept, not with the question. The question may ask: “How does [Paragraph A] connect to [Paragraph B]? But dig deeper to extract the concept – in this case, understanding how various parts of any text might fit together.

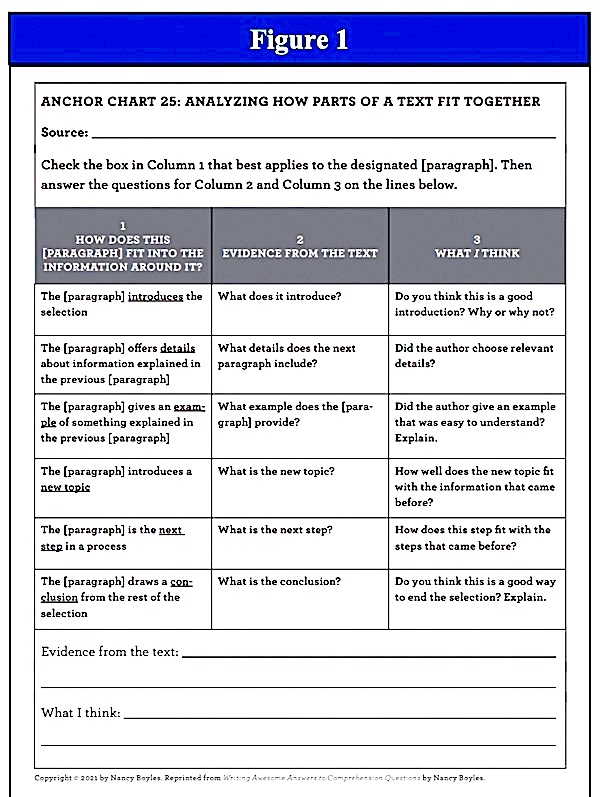

Introduce this in a quick mini-lesson, enumerating some of the possibilities. Paragraphs might offer details about information explained in a previous paragraph. They might introduce a new topic, explain the next step in a process, or draw a conclusion based on previous information in a passage. There could be other connections, too, but you just need a place to begin.

Next, create an anchor chart with several of these possibilities listed and ask students (individually or with a partner) to analyze a short text of a few paragraphs to figure out the connections between the parts of the selection. It’s these anchor charts for analyzing literary concepts that hold the key to comprehension.

When we ask students a question about a familiar concept, perhaps character traits, they know exactly what needs to be analyzed. But when the concept is more complex, they aren’t sure where to begin. My Writing Awesome Answers book takes the guesswork out of this by providing anchor charts and checklists for 41 different concepts. But students still need other guidance, as well.

When you move from the concept to the question, they need oral rehearsal of that question before they write their answer. Oral rehearsal is different from conversation where the language is more informal, and students get feedback and encouragement from their peers as they talk. For oral rehearsal, students say their response exactly as they will write it. A cue card with sentence stems can offer the prompts they need to get started. Make this a partner activity for shared practice.

For even more support, analyze written responses that have received a full score: What made these answers strong? Analyze responses that were partially correct: How could they be improved? And finally, offer up an answer frame for students who still need an extra boost of confidence (but also remember to wean them from the use of these to avoid learned helplessness.) Notice that the answer frame is not the only instructional support. In fact, it is last in a long lineup of strategies that truly build the comprehension students need to produce a quality answer.

With a focus on the comprehension priorities that matter most, and the right tools to support readers, we can accelerate reading achievement for our students who need it most.

Images: Copyright © 2021 by Nancy Boyles. Shared with the permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Over the course of her career she has received numerous awards, including the New England Reading Association’s Outstanding Literacy Leader Award. As a consultant, Nancy works with districts and educational agencies to provide workshops, model lessons in classrooms, and assist with curriculum development. Also see her 2014 article for MiddleWeb, “10 Steps to Deeper Student Reading.”

Thank you! I’m a Swedish teacher/librarian and I’m always on the lookout for new ways to work with reading comprehension. This was a great new angle and I love it.