What Learning in Two Languages Looks Like

A MiddleWeb Blog

My first language is Vietnamese, but I struggle to read anything beyond road signs and names of businesses like bakery, restaurant, hotel, etc., in that language today.

My first language is Vietnamese, but I struggle to read anything beyond road signs and names of businesses like bakery, restaurant, hotel, etc., in that language today.

As an adult I sometimes wonder what my life would have been like if I developed my home language like I have nurtured English. Unfortunately, my school district did not offer Vietnamese bilingual programs when I was in school.

Though many of you are language specialists just like me, some of us are not multilingual educators. However, both language specialists and multilingual educators serve under the same banner: to boost achievement for multilingual students.

That’s why I have interviewed Dr. Ester de Jong to share from her book called Foundations for Multilingualism in Education: From Principles to Practice to provide an introduction into this branch of instruction. You can also listen to the podcast that inspired this article.

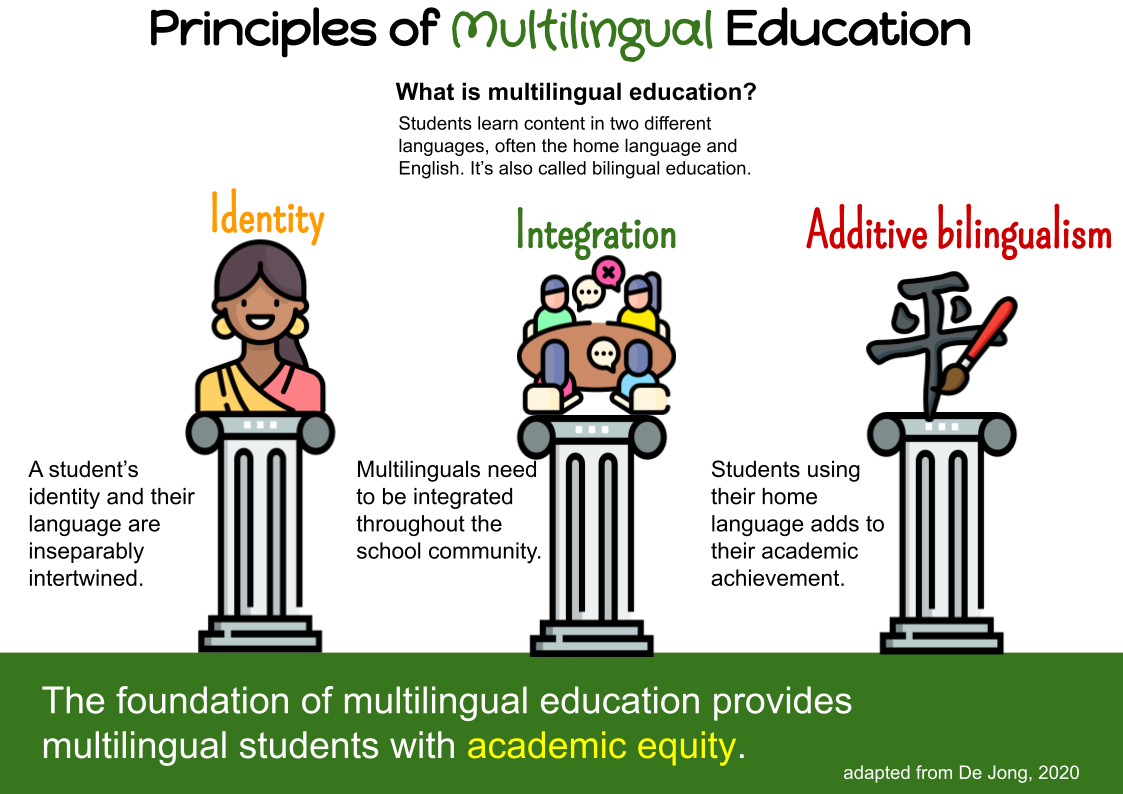

What is bilingual education?

There are many forms of bilingual programs, but the core of these programs is to have students learn grade-level content in two languages throughout the day. Often the two languages are a selected home language and English.

Imagine an eighth-grader named Yu Fei, who just came to the US from China. When Yu Fei enrolls in her school district, there is a Chinese bilingual program. In her particular school, she attends morning classes that are delivered in English while her afternoon classes are taught in Mandarin. Yu Fei is learning the state-mandated curriculum, but she is accessing and engaging with the content in two languages. This is what bilingual schooling can look like. This is how schools can support multilingualism in students like Yu Fei.

A foundation of equity

Dr. de Jong shares that the foundation of multilingualism is educational equity. When Yu Fei joins that school, she gets to learn the same grade-level content as others. She also gets to utilize her already highly established Chinese language to access content. Because some of the classes are in Mandarin, she can learn without requiring remediation, which sometimes waters down the curriculum so it is more accessible for beginning English learners. She is not warehoused in a resource room and shuffled away from her classmates until she demonstrates “enough” English proficiency.

By providing instruction in students’ home languages, multilingual education positions MLs to be on equal footing to their peers. Learning in their home languages prevents a widening education gap as a result of well-intentioned remediation and intervention programs that sometimes offer a less rigorous learning experience.

Educational equity supports three key principles of multilingualism: identity, structuring for integration, and additive bilingualism.

Identity

Multilingual education retains students’ deeply rooted connection to their culture through maintaining and expanding their home languages. Students do not have to give up part of their home language, and by extension, their identity, to learn.

Structuring for integration

Under this principle, students come together on an equal status. Multilingual students enjoy the same experiences as monolingual learners, they share the same campus resources, and they have full access to the same services. Multilinguals are fully part of the school community instead of housed in separate portable classes tucked away in the far corner of the campus.

For example, when Yu Fei goes to math class, the class is located on the math wing where all students go for math classes. Structuring for integration means multilinguals and their learners are part of the school community and busy participating in all areas of it – from after-school clubs to the cafeteria. Lastly, this also means that students are free to use their home languages everywhere at school, not just in their multilingual programs.

Additive bilingualism

This principle is about valuing students’ home language use at school while still teaching them English. The home language adds to students’ understanding and fosters engagement. Home language does not drag down learning but supercharges it. We want to expand students’ linguistic repertoire because then they can wield more tools to access content and to express themselves.

I find that this is the main distinction that separates me as a language specialist from my multilingual educator peers. For far too many years, I thought my job as a language specialist was to explicitly transition students into English. To do that, implicitly, meant transitioning them out of their home language. I wrongly focused on English acquisition above all else, including home language use, which was a culturally destructive practice.

Now I have realized that my job is to join my multilingual educator colleagues in helping students acquire English while still maintaining and expanding their home language skills. Learning one language can’t come at the expense of another.

Applying the principles

Dr. de Jong implores us to find how we can apply these principles to our context. How multilingual programs look will differ, as they should, from school to school. Though multilingual programs will take the shape of the context, these three key principles need to remain embedded in every program.

Even if language specialists and many content teachers are not multilingual educators by certification, we can encourage students to develop their home language as they acquire an additional language.

Dr. de Jong has taught me that whether students find themselves with a language specialist or a content teacher, our role is to provide educational equity. We do this by using multilingual practices that add languages rather than subtract them.

And when students like Yu Fei add to their language tools, it multiplies what they can do.