Make It Happen: Reading Growth for All Students

The need to support under-developed readers in the middle grades is growing. We’re grateful to respected literacy consultant Laura Robb for sharing these tested strategies from her own collaborative efforts in real classrooms.

Prior to the restrictions of COVID-19, I worked with students entering fifth grade who were reading at a first grade instructional level. My goal was to find ways to develop their reading skill, so they could enjoy success at school and develop a personal reading life.

During the first week of school, I conferred with students to discover how they felt about reading. “I hate reading” and “I never read” were responses I repeatedly received.

Most of the 40 students who conferred with me had never read a book. During class they checked out books they couldn’t read and aimlessly flipped through pages.

By the middle grades their frustration had transformed into indifference toward reading, a lack of self-confidence, and a fear of peers “making fun” of them when teachers asked them to read aloud. They didn’t want to talk about reading.

But they enjoyed talking about family, friends, and what they did during their free time. Our conversations forged connections between students and me and were first steps to building trusting relationships.

As I worked with students, I had more questions about their reading lives than answers. Picture this: I’m teaching a group of fifth graders reading at a first grade level in a class that Stacey Yost, Bridget Wilson, and I co- teach. Two months have passed, and though we extend the invitation every day, no one has taken a book home to read.

Finally, the three of us meet and agree to ask students: We see how much you’re enjoying independent reading in class; why aren’t you taking books home?

We order opaque plastic envelopes and explain that no one would know a book is inside. That day most students claim an envelope and put in one or two books. Equally important, we learn that when we’re perplexed about an issue that involves and affects most students, it’s helpful to ask them.

To identify how best to support developing readers (students reading two or more years below grade level) we teachers and administrators should generate open-ended questions to help us better understand students’ needs.

When I am a part of these kinds of meetings in schools, I repeatedly hear these questions:

• How can we support developing readers in the core classroom?

• Why aren’t developing readers making progress?

• How does the research on reading inform developing readers’ needs?

• Do ELA classes have enough time to meet all children’s needs?

• Why aren’t mini-lessons supporting students’ application of reading strategies to their own reading?

These questions are invitations to gather additional information and then consider options. In this way the work becomes a shared inquiry. In our case, Stacey, Bridget, and I use shared inquiry to embrace an asset-based model and begin by referring to these students as developing readers instead of the deficit term, struggling readers.

The Why Behind “Developing Readers”

It’s difficult to find a term with positive connotations that refers to students who read two or more years below grade level. The term “developing readers” actually describes each one of us at diverse points in our learning, and that’s what I love about the term.

Any time you or I read a book with little background knowledge of the topic, we might have to reread and/or pause and enlarge our background knowledge to comprehend and recall. Reading at our frustration level is humbling as it creates an understanding of what it’s like for students who lack the vocabulary and background knowledge to read texts above their instructional reading levels.

The term “developing readers” offers hope that with practice and empathetic teacher support, every developing reader can improve enough to read and learn from grade level materials.

However, for many of the developing readers in fifth and sixth grade that my teacher colleagues and I supported, the limited practice they completed during mini-lessons wasn’t enough for them to apply these experiences to their instructional and independent reading.

For weeks, this question was front and center in my mind: Why aren’t mini-lessons supporting students’ application of reading strategies to their own reading?

In the first edition of Teaching Reading in Middle School, I refer to the term “guided practice “— offering developing readers and any students requiring extra practice opportunities to learn and improve with easy, short texts (Robb, 2000). Guided practice is part of instructional reading and an interim step between mini-lessons and students’ application of them to their reading (Robb, 2020).

The lessons I developed and then adjusted and refined with students’ feedback eventually turned into the book Guided Practice for Reading Growth, Grades 4 to 8 (Corwin, 2020). David L. Harrison, an award-winning poet, wrote poems and short texts for the lessons based on topics students and teachers suggested and our desire for cultural diversity.

Guided practice lessons enable students to successfully transition from the mini-lessons you present to applying what’s been modeled for them to their instructional and independent reading.

Scheduling Guided Practice Lessons

The beauty and benefit of guided practice is that teachers can provide much-needed interventions before students dive into long texts. It’s an opportunity to repair small confusions for developing and proficient readers before they grow into large obstacles that can diminish students’ progress and reading comprehension.

The bridge that guided practice forms between mini-lessons and student application to texts can increase the self-confidence needed to work hard and move forward.

Most guided practice lessons last fifteen to thirty minutes over two to three days. You’ll want to reserve three consecutive days over two to three weeks to facilitate a set of guided practice lessons. The lessons in our book invite you to choose those that meet your students’ needs. To personalize selecting lessons for your students, you’ll find a chart that identifies the skills and strategies each lesson addresses.

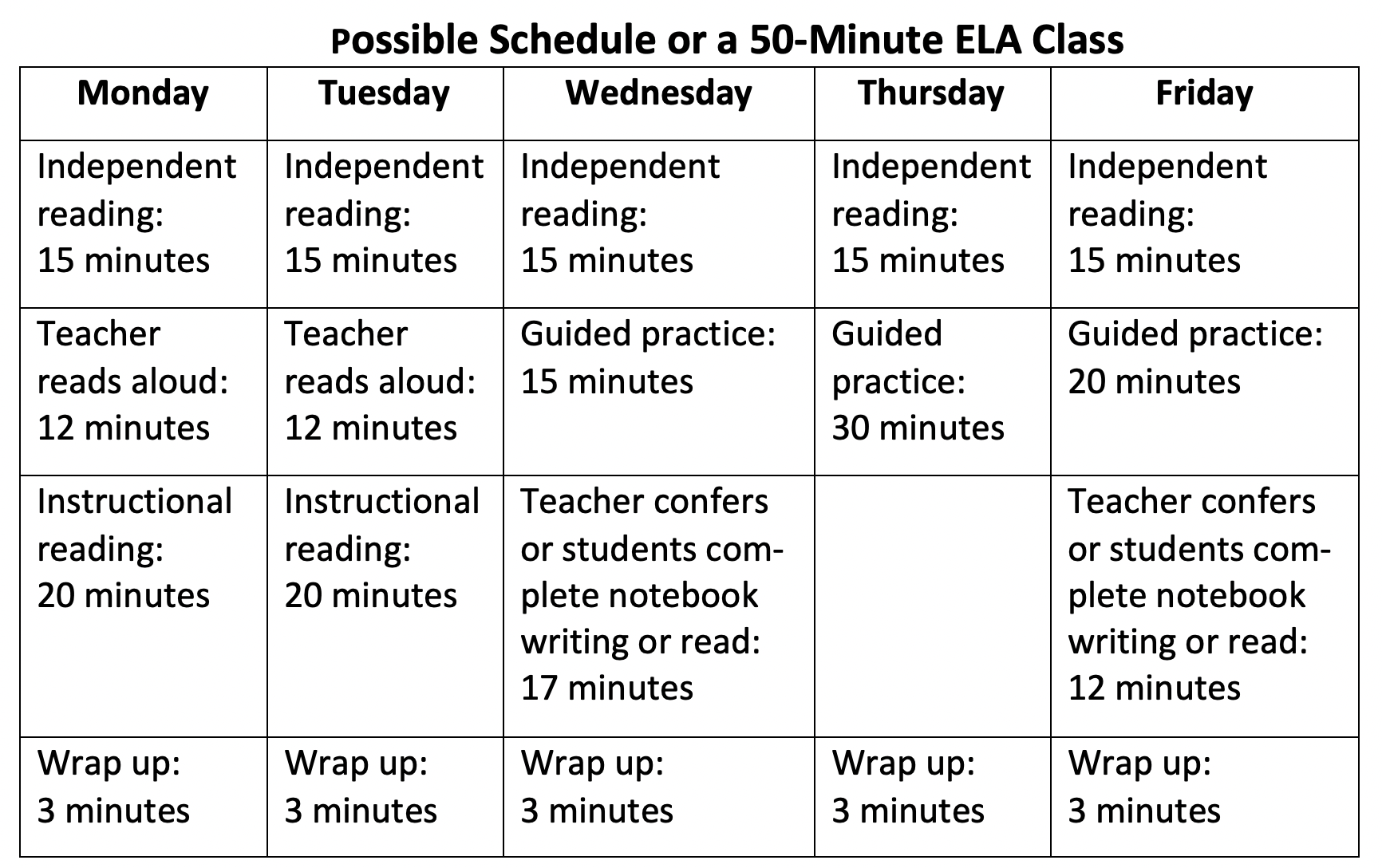

This possible schedule for a 50-minute ELA class allows you to present these lessons on any two to three consecutive days, depending on the amount of time your students need. To adjust instructional reading time, you can reduce or increase the amount of time for read alouds and conferring or notebook writing.

Guided practice is not a substitute for instructional reading of long texts. To increase students’ reading skill so they can find pleasure in reading, I developed two different kinds of guided practice lessons that invite students to do most of the thinking.

2 Types of Guided Practice Lessons

I created two different lessons: Partner Discussion and Shared Reading Lessons. In the book, both types of lessons open with students enlarging their background knowledge by watching one to two videos, completing word work, and then silently following as teachers read the text out loud with expression and fluency. Lessons close with quick assessment ideas and suggestions for supporting students.

Partner Discussion Lessons ask teachers to pair up students and invite partners to select questions or prompts they’d like to discuss. Teachers remind students to provide text details to support their responses. In addition, writing about reading that can improve students’ comprehension is a feature of these lessons. There are guidelines for teachers to model in a “cold write” for students who in turn use the model as a resource when they complete notebook writing.

Shared Reading Lessons invite students to think about a text’s meaning independently. Teachers divide texts into meaningful chunks, pose open-ended questions, provide think-time, and ask students to volunteer and respond using text details to support ideas. Students will risk sharing ideas in classes where teachers build trusting relationships and create a community of learners where everyone feels safe.

So that teachers can develop their own guided practice lessons, the book’s Appendix has guidelines for creating both types of lessons using the extra poems and short texts by David Harrison as well as lists of resources for finding more high quality poems and short texts.

The targeted guided practice lessons that students experience can positively affect their reading lives and identities, increase their reading skill, and inspire their desire to read to learn and for pleasure and enjoyment.

10 Reasons to Use Guided Practice

For students in grades 4-8 to progress, they need to work in an environment where kindness and support for one another matters. As learners thoughtfully move through engaging texts, they become invested in the reading, thinking, and problem solving, and their experiences highlight the benefits of helping one another.

Because guided practice lessons increase students’ skill and pleasure in reading, they can move developing readers forward in the 10 ways that follow:

(1) Personal efficacy and power of YET: As students improve, they build their personal efficacy and apply Carol Dweck’s power of YET to daily learning experiences. The power of YET helps students realize that their successes grow out of daily practice and teacher support. With time, hard work, and support, they come to understand that it’s possible to reach goals; “I can’t do it” becomes “I can’t do it yet.”

(2) Ability to talk about their reading: By observing their teacher talk about books and practicing with a partner, students improve the skill of communicating their thoughts and ideas to others. Talking about reading is a complex process that asks students to develop ideas and clarify them so others understand their position and thinking process.

(3) Sense of community: As students collaborate with each other and their teacher, they develop the relationships and support network that continually build a community of learners. Teamwork increases trust and empathy through students’ shared discussions about books and projects, and trust and empathy are like the mortar between bricks, bonding members to one another.

(4) Reflection and self-evaluation: Students reflect during the lessons when they turn-and-talk to a partner, refine and adjust their hunches, and jot thoughts in their notebooks. During conferences with their teacher, students begin to see themselves as readers, especially when they discuss why they enjoy a specific book and why they choose to read during free time. In addition, students can review several weeks of notebook writing or focus on specific entries to self-evaluate their progress with reading and growth in writing about reading.

(5) Use of text details to think: Recalling facts and details is a basic aspect of comprehension. Shared reading lessons nudge students to use details and facts to infer, connect ideas within a text, determine important information, and support diverse interpretations.

(6) Reading fluency: During each shared reading lesson, students hear their teacher’s fluent reading of texts as they follow and read silently. When students reread short texts they have stored in a folder and/or choose a poem to practice and perform, they can develop fluent, expressive reading that reflects their comprehension and interpretation.

(7) Listening: When students talk about reading during pair-shares and small group discussions and conferences with teachers, they learn to focus, listen to and value diverse interpretations, and observe how peers organize their ideas and cite text evidence.

(8) Word knowledge: During lessons students will practice using context to figure out a word’s meaning; they’ll also observe their teacher doing this during interactive read-alouds. Over time the skill of using context clues to figure out a word’s meaning will be a strategy that students can apply with ease.

(9) Background knowledge: All lessons build students’ background knowledge by having them watch, listen to, and discuss recommended videos. In addition, you’ll introduce vocabulary that students need to comprehend the text. Having prior knowledge increases students’ understanding and enjoyment of their reading.

(10) Self-confidence & Reading Identities: As students’ reading skill improves, so does their self-confidence and willingness to continue to choose to read self-selected books at school and home. When students enjoy reading, they develop positive reading identities and see themselves as readers that risk exploring new genres, topics, and authors.

Closing Thoughts

Guided practice lessons can support a group of students or an entire class that would benefit from additional practice applying a strategy, enlarging background knowledge of a topic, interpreting texts, finding text evidence to support their thinking, writing about reading in notebooks, and having meaningful discussions that can deepen understanding and facilitate inter-text and across-text connections.

By including guided practice lessons in your instructional reading options, you offer students opportunities to strengthen their reading skill and steadily move forward.

References

Allington, R. L. & McGill-Frazen, A. M. (2021). “Reading volume and reading achievement: A review of recent research.” Reading Research Quarterly, 0(0): 1-8, Newark, DE: ILA.

Dweck, C. S. (2007). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY: Random House.

Robb, L. (2000). Teaching Reading in Middle School: A Strategic Approach to Teach Reading That Improves Comprehension and Thinking, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Robb, L. & Harrison, D. L. (2020). Guided Practice for Reading Growth: Texts and Lessons to Improve Fluency, Comprehension, and Vocabulary. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Literacy.

Read a MiddleWeb review of

Laura Robb’s Guided Practice for Reading

Laura was named NCTE’s recipient of the Richard W. Halle Award for Outstanding Middle Level Educator in 2016. Her latest book, with poet David Harrison, is Guided Practice for Reading Growth: Texts and Lessons to Improve Fluency, Comprehension, and Vocabulary (Corwin, 2020).