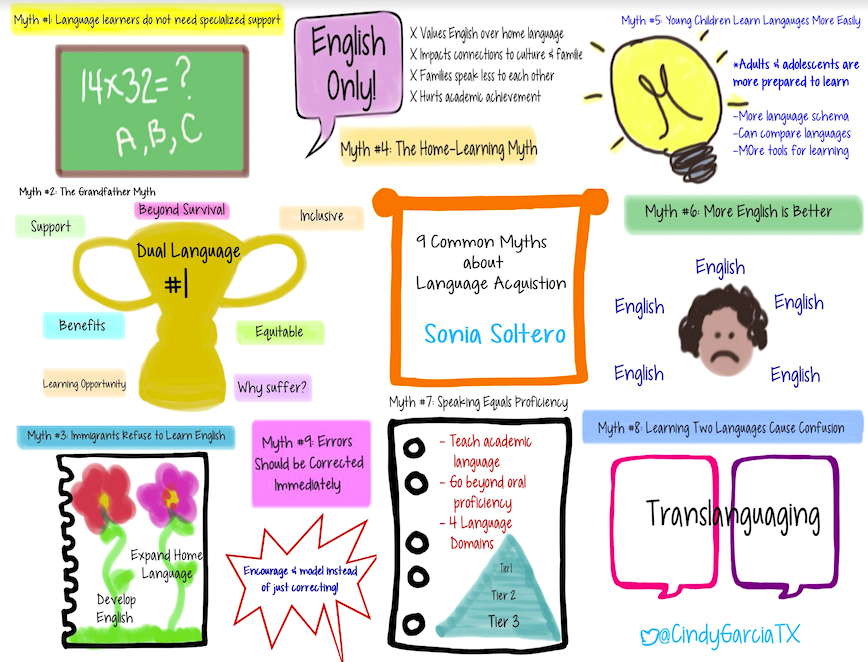

9 Damaging Myths about Dual Language Acquisition

A MiddleWeb Blog

There are many pervasive and detrimental myths about multi-lingual learners that can prevent MLs from experiencing the equitable, rigorous learning opportunities they have a right to expect.

There are many pervasive and detrimental myths about multi-lingual learners that can prevent MLs from experiencing the equitable, rigorous learning opportunities they have a right to expect.

In Dr. Sonia Soltero’s classic book, Schoolwide Approaches to Educating ELLs: Creating Linguistically and Culturally Responsive K-12 Schools, there is an entire section on the nine most harmful and widespread myths – beliefs so damaging they can sever students’ connections to their communities and families.

This article summarizes the key insights Dr. Soltero shared during our podcast conversation. Highly recommended for pre-service teachers new to the field, admins who want to learn more about dual language acquisition, and veteran language specialists who want confirmation that they’re doing the right things.

Myth 1: Language learners do not need specialized support

The truth is that it takes a highly skilled teacher in both content and language development because dual language education is highly complex. Languages are highly sophisticated, intricate creations of society. To learn a new language requires highly specialized, consistent support.

Myth 2: The “Grandfather” myth

Some people point out that an older relative who did not receive dual language education still survived academically. Since these people coped, why does the current generation need support? Schools offer the best they can from their level of understanding, the argument goes.

In the past, dual language acquisition programs did not exist. Older generations missed this learning opportunity, but they still would have benefited greatly from it. Why make the young today suffer if there’s a more inclusive, equitable way?

Myth 3: Immigrants refuse to learn English

Immigrants absolutely want their children to learn English — sadly, sometimes at the expense of their own home languages. Dual language acquisition programs simply believe that immigrants can and should learn English while at the same time strengthening and expanding their home language proficiency.

Myth 4: The home-learning myth

Some families feel the pressure of wanting their children to be successful at school and in society. The pressure causes some immigrant caregivers to decide to make their home an English-only place. These guardians elect to speak to their children only in English and expect their children to respond in English as well. Sadly, the parents who choose this route often talk less to their children as their English proficiency hampers communication.

English-only practice at home explicitly values English over other languages. This is not only detrimental to academic achievement but also destructive to the linguistic bridge that connects students to their culture and families.

Research supports the opposite approach. The more established the literacy practices in students’ home languages, the more successful students will be in acquiring a new language (Cummins, 2014).

Myth 5: Young children learn languages more easily

Not true. Adolescents and adults are better positioned to learn language more efficiently and effectively than young children. The older you are, the more language schemata you have to compare languages, find similarities, and notice differences. In this comparison, adolescents and adults have more tools to learn a new language.

Myth 6: More English is better

This myth is transplanted – inappropriately – from foreign-language programs where teachers advocate for maximum exposure to the language in focus. Take, for example, a student living in British Columbia, Canada. They are learning French, but the community speaks a mix of languages and the main one is English. In this case students have limited opportunities to practice French outside of the classroom. Therefore, they may be exposed to only French during French class.

However, we cannot apply a practice used in foreign language classes to dual language acquisition programs. Often in districts that have implemented dual language programs, the language of the community is English. For students who are learning English, simply going about the community already offers extra exposure. Focus your energies instead on creating a welcoming environment.

Myth 7: Speaking equals proficiency

I once was conferencing with a multi-lingual eighth grader to help him gather research for his report. As we looked at the article together, I started to realize that the student could decode the text and read every word, but he did not understand the meaning of the sentence. I thought he was on grade level because his oral proficiency was on par with native English speakers.

Students’ oral proficiency can mask their need for better academic language proficiency. We must teach the academic language of our content and not assume that oral proficiency is an indicator of academic mastery. Try writing a model response or even drawing abstract vocabulary to help students grow their tiered vocabulary.

Myth 8: Learning two languages causes confusion

For example, in Lao (my home language growing up), we do not use “s” for plurals. We use a number and an article to express plurals. When a person wants to say five books, the literal translation would be “book 5 unit.”

Translanguaging often frightens well-meaning educators who worry that students aren’t understanding their lessons or are backtracking on progress. Language specialists should assure their colleagues that translanguaging is not only a natural part of bilingualism, it is also a sign of intellectual growth.

As students develop more language proficiency, they will blend the language features less often. When blending does occur at the highest level of linguistic mastery, it’s intentional.

Myth 9: Errors should be corrected immediately

Errors need to be addressed but not necessarily corrected right at that moment. It’s more effective and encouraging to model the language and explicitly teach grammar and mechanical conventions.

Returning to the plural example from above, you may notice that you need to teach your students who speak Lao that in the English language, we place an “s” after most words to show something is plural. Then when you notice that your Lao student forgets to use “s,” ask them how to say five books in Lao. Then ask them to communicate the same thing in English using an “s.”

This combination of modeling and direct instruction allows the point to sink in more deeply without feeling overwhelming or urgent.

Don’t let the myths become reality

Sadly, some of these myths become a reality for many language learners. These harmful beliefs find their way into schools and homes. They eventually shape school policies and home practices. Such policies and practices can widen the achievement gap at school and cause students to feel that their cultures are not welcomed or valued in the schools of an English-dominant society.

Resources

Cummins, J. (2014, November 14). Reversing Underachievement among Immigration-Background Students: What Does the Research Say? Politeknik.

Soltero, S. (2011) Schoolwide Approaches to Educating ELLs: Creating Linguistically and Culturally Responsive K-12 Schools. Heinemann Illustrated Edition.