We Hold All the Keys to Student Participation

A MiddleWeb Blog

When it comes to participation, students either rise – or sink – to the standard of their teachers.

Step 1: The Grind – A teacher works for hours…developing and refining a lesson or learning task in hope that students will find it relevant, challenging, and engaging.

Step 2: The Glitter – At the start of class, the teacher does everything possible (e.g., utilizes multimedia, current events, statistics, etc.) in an effort to introduce the topic or task in a way that sparkles and spurs learner interest.

Step 3: The Debacle – The teacher asks a poignant, well-phrased question to gain insight and input from the class…only to be met with an awkward silence or a short, superficial response from the same 2 or 3 students that always chime in.

Sound familiar? Don’t feel too bad – particularly if you teach Middle School. After all, early adolescence marks a shift in many students’ behaviors and attitudes towards learning.

Academic interest, effort, and participation often drop, even in students that have previously thrived in the classroom. Others simply withdraw from contributing due to the nagging worry of ridicule from peers.

A Classroom Culture That Encourages and Monitors Participation

Educators can begin the process of helping students overcome their hesitancy to participate by establishing (and supporting) a “culture of contribution” early in the school year.

For those of us looking to help our students hit the ground running, here are eight practices and approaches supported by research and recommended by effective teachers I’ve worked with and observed.

► Establish norms now. In the opening days/weeks of class, work with students to establish classroom norms that include specific expectations for participation. I was recently in a classroom where the teacher introduced rules that she had co-authored with her students the previous year. One of the expectations was…In our class WE ALL CONTRIBUTE and learn from the ideas of others.

She invited students in her new class to review a copy of these rules. She encouraged each student to make notes about what should be added, changed, or deleted before discussing their ideas in small groups as she roamed the room and listened.

The next day, the teacher returned with a new draft based on the comments/ideas collected from her students throughout the day. Their sense of ownership was palpable.

► Don’t omit think time. Create a variety of opportunities for students to pause, reflect, discuss, and refine their ideas during class. Determine beforehand what parts of the lesson (and what questions) will encourage critical thinking and participation. Make an effort to reduce teacher talk-time and increase the number of students who talk, share, and explain their thoughts and answers in class.

► Be deliberate about grouping students. Smaller groups of two to four individuals encourage participation and make it more difficult for students to “hide out.” Instead of asking students to simply “find a partner” or just numbering students off randomly, use your knowledge of students’ personalities, performance, and skill level to anticipate who is likely to work the best with whom and which groupings will gain the most from each other.

► Model what participation looks like. As teachers, many times we ask for students to contribute to an activity or discussion, but don’t make clear what effective contribution looks like. Asking someone to turn and talk to their partner will have much poorer results than demonstrating (and allowing students to practice) the process of formulating and sharing their thoughts, as well as listening to and learning from another’s perspectives.

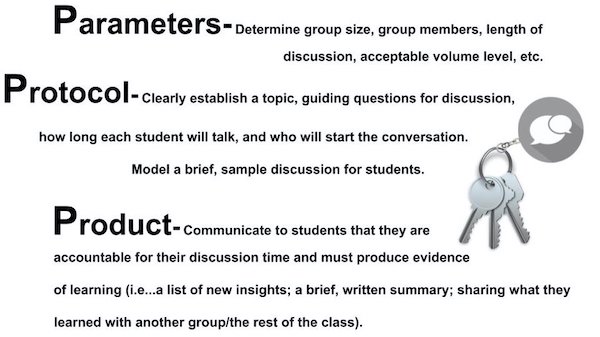

During my own college classes and school classroom visits, I encourage teachers to make sure that – at a minimum – they have clearly communicated the necessary parameters, protocols, and product(s) before turning students loose.

► Collect evidence of student participation. In a previous post, I provided some suggestions for assessing the level of student engagement in our classrooms. The idea is to find a way to really know how much each student is participating. Over the past year, I have also begun carrying around a clipboard with a duplicate class roll attached.

On it, I use a system of symbols to make notes about which students participate during class and what form their participation takes. For example, I have a symbol for asking a question of the teacher, responding to a question posed by the teacher, responding the comment of a peer, etc. Doing this allows me to quickly chart interactions over several days and determine what instructional adjustments I need to make to strengthen participation.

► Involve the “introverts.” Make an effort to affirm and highlight the ideas of students who are less apt to participate. Whether students are working independently or in small groups, teachers should be moving around the room, scanning student work and listening for insightful comments.

When you come across an idea from a quiet student, ask if they would be willing to share their comments, solution to a problem, etc. with the rest of the class. If the student is not comfortable doing so, ask if YOU can share their idea.

► Don’t let kids off the hook. Sometimes a student is asked a question and hasn’t quite formulated a response. Other times students have something to contribute and would rather pretend that they don’t. In either case, it’s okay to tell a student that you will come back to them after a couple more responses to allow them more think time. The important thing is to avoid sending a message that “I don’t know” is an acceptable answer.

► Always include student choice. Research in methodologies like Universal Design for Learning (UDL), Differentiated Instruction, and in student engagement generally all underscore the benefits of student choice and control on classroom participation (Capp, 2017; Reeve, 2012; Tomlinson, 2014).

Providing multiple options for task completion, different stations where students can participate simultaneously, tiered activities, choice boards based on interest and readiness, and a variety of other strategies are ways to encourage more students to take part in learning.

An Expectation for Participation

Recently I was at a park sitting in the shade with my dog. A group of kids about 11 to 12 years old were playing nearby when one of them cut away from the pack to ask his dad for something. When his dad refused without much thought, the kiddo stomped, whined, and threw a fit for several minutes.

Eventually, the kid gave up and walked to another part of the park where his mom was visiting with a few other parents. After waiting patiently for her to finish her conversation, he asked her the same question. She thought for a few seconds, shook her head, and offered a brief, firm justification for telling him no. Interestingly, he had a completely different reaction to this parent. His shoulders sagged, but – to my surprise – the kid didn’t argue or fuss. He simply turned around and went back to playing with his friends.

Simply put…his actions were determined by the expectations he had of others. One parent was willing to put up with his sass. The other one…not a chance.

Over the past few years I have seen a similar phenomenon in the schools and classrooms that I visit or observe. The single most influential factor determining how much a student participates is NOT the subject area or topic being studied…nor is it the mix of kids in the classroom. Rather, it’s the degree to which students are expected to participate by the teacher.

Students either rise – or sink – to the standard of their teachers. If we desire a classroom where all students are engaged, we must work strategically to encourage, support, and monitor the participation of each of our learners.

The Keys to Participation Are in Our Hands

Many middle school students worry about participating in front of peers and step down their efforts accordingly. The consequences of disengagement are both behavioral and academic, including disruptive behavior, alienation, and a downward achievement spiral.

Most of us only participate as much as we have to. So why not raise the level of participation required? I hope these ideas will help!

References

Capp, M. J. (2017). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A meta-analysis of literature between 2013 and 2016. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(8), 791-807.

Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., Papworth, B., & Ginns, P. (2016). Students’ interpersonal relationships, personal best (PB) goals, and academic engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 65-76.

Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149-172). Springer, Boston, MA.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. ASCD.

Turner, J. C., Christensen, A., Kackar-Cam, H. Z., Trucano, M., & Fulmer, S. M. (2014). Enhancing students’ engagement: Report of a 3-year intervention with middle school teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 51(6), 1195-1226.

Thank you for sharing. Although I am not a teacher currently, I taught middle school for 15 years. I wholeheartedly agree that the teachers’ expectations and courage make or break the students’ participation.