Ways We Can Spark Student Reflection

Help students become metacognitive thinkers through self-conferencing, portfolio creation, and goal setting. Have you tried a single-point rubric?

If we want our students to learn how to reflect on their writing and reading, then we must look for different classroom routines that build in time for meaningful contemplation.

In classrooms that support authentic reflection, students practice to improve their awareness and their ability to analyze their own thinking processes (metacognition).

In writing instruction, a natural consequence is that they engage in a struggle with the quality of their writing pieces – viewing the writing process as recursive instead of linear, and embedding revision and editing across the process and as early as the prewriting (planning) stage.

Routinely reflecting on reading helps students learn to think about how their reading selections have changed and encourages them to read more regularly – promoting content mastery and fostering student development of monitoring, self-evaluation, and reflection skills.

If we imagine our students as essential evaluators of their process, then we are promising them one of the best opportunities that a classroom can afford – the opportunity to help blaze their own trail throughout their literacy journey.

Reflection leads to good decisions

We must ask ourselves what are the most effective practices we can use to help students make successful decisions about their writing and reading? By exercising our own metacognition and examining how we delegate student responsibility for self-assessment and ongoing reflection, we can determine:

- what is working for our students and for us,

- what new strategies we may choose to adapt, and

- what value our students will ultimately place on reflection as a part of the learning process.

If our priority goal is to teach our students how to learn instead of what to learn, then we must recognize that students cannot blaze their own pathways if they are not regularly engaging in self-reflection. Self reflection fuels self direction.

When students engage in a close reading of their work for purposes of self assessment and reflection, they are making choices about what to keep and what to change. Our teaching practices can help our students learn to value this regular reflection as an essential part of their learning process.

So how do we create these opportunities for students to be the essential evaluators of their reading, writing and, ultimately, learning processes? Here are some ideas.

► Self-Conferences, Portfolios, and Goal Setting

Self-evaluation does not happen magically. Students need to learn to reflect through practice. We encourage students to be reflective by making reflection part of the writing and reading experience: What did you write today that you are proud of? What did you work hard at today? What did you learn about writing opinion today?

Students may pair with a partner to share their answers to these questions, write responses in their writer’s or reader’s notebook, or share their thoughts with the whole class. If we believe self-assessment and reflection are valuable, we make time for this self-conferencing in our daily practice.

When we build in opportunities for reflection, we also ask students to become familiar with goal setting. Portfolio systems usually ask them to create both short- and long-term goals with a teacher or by themselves.

Often, discussion about writing goals begins in writing workshop as a whole group discussion. Later, students and their teacher can work together to set goals in student-teacher conferences, after the students have had a chance to think about possible goals by reviewing their portfolio and writer’s notebook.

Reflection is key to developing an authentic portfolio. Students respond well to the challenge of evaluating their own work by selecting pieces for their showcase portfolio.

A reflective essay can be a whole-class activity. Ask students to write an essay to discuss how their writing (or reading) has improved during the first/second half of the year (or the semester). Ask them to include some examples to back up their ideas, using evidence from their portfolio selections. The students can close their essay by giving themselves the grade they think they deserve for that marking period or year.

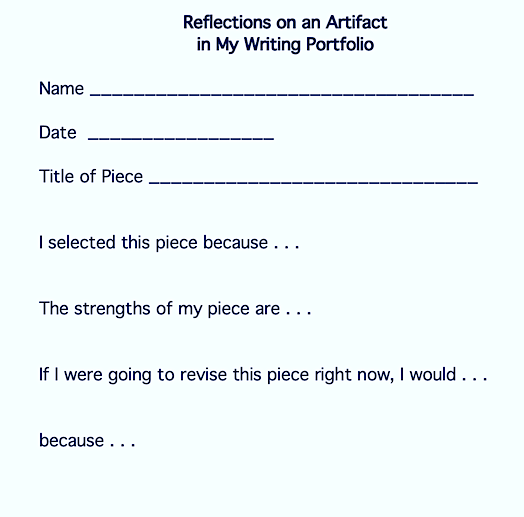

These essays can be included in the students’ portfolios as a letter to readers. Above are some questions your students can use to reflect on a piece (artifact) of their own writing. Using a form like this one can be less stressful and threatening when students are learning how to offer reflections. Eventually, students can choose their own format to tag artifacts included in their portfolio or offer final reflections on their writing and reading progress.

► Single-Point Rubrics

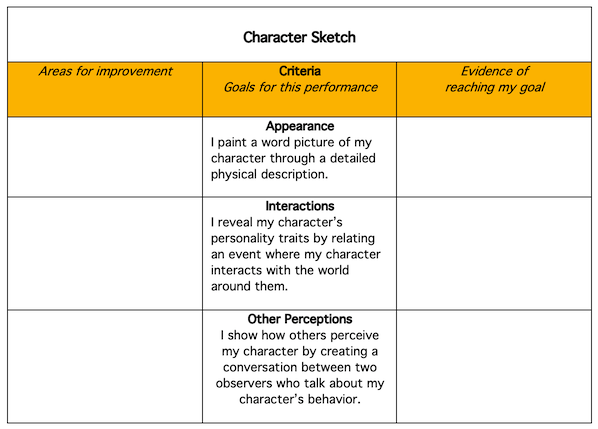

I first learned of the single-point rubric from Jennifer Gonzalez at her Cult of Pedagogy website. Have you ever questioned the value of typical rubrics that provide your students with stock descriptions of what is proficient, not quite proficient and not satisfactory at all? What if, instead, you help them wholly focus their attention on what you want them to strive for and attain?

The single-point rubric only describes what students are aiming for and lists three or four areas they are going to work on as they draft, revise, and edit their work. There’s a whole lot less reading of handouts for them to do – and that is so helpful, particularly for your striving literacy learners.

A single-point rubric provides open-ended areas for students to comment on their progress toward the criteria. Their comments can help teachers give timely and ongoing feedback during one-on-one conferences.

Students can set doable short and/or long term goals with the teacher before they leave the conference. They might also write a reflection in their writer’s notebook about what they will do this week or in the next weeks to realize their goal(s).

► 3-2-1 Strategy

This useful strategy gives students a chance to reflect by using three questions or statements. The beauty of this practice is its perfect fit for use across the content areas.

In social studies class, the teacher can ask the students to summarize three big ideas gleaned from the text, share two insights about what aspects of their reading are most interesting to them, and ask one question about the text.

In writing workshop, students can write about three things they have tried today, two questions they are still wondering about, and one thing they will try in the next writing session.

Another example of the 3-2-1 strategy is to use a reader’s notebook to record the title and author(s) of the book and write about three things they’ve discovered, two interesting or surprising things, and one question they have for the author or another reader of the text.

The advantage of the 3-2-1 strategy is its flexible nature to engage K-12 students actively and meaningfully with text. Here are some ideas about using the 3-2-1 strategy to promote critical thinking and reflection.

The 3-2-1 strategy also gives students a voice in class routines and immediate feedback so you can make adjustments as you move from day to day. Allowing your students to share what they know and what they don’t know helps you provide more support by differentiating instruction and/or doing some reteaching when it’s appropriate.

Don’t give up on reflection!

Building in reflection isn’t easy – it takes a lot of practice. Growing student writers and readers never happens instantly. It happens over time. But it isn’t accidental either. It takes persistence and a boatload of patience.

Don’t give up if you are disappointed with students’ initial attempts at reflection. As students continue to have opportunities to share their reflections, they will improve. Daily reflection will help them become metacognitive thinkers who imagine the possibilities arising from their own efforts and make choices for independent writing and reading time that are sensible and meaningful.

Lynne is currently finishing her eighth book for Stenhouse Publishers, Welcome to Reading Workshop, with co-author and literacy teacher Brenda Krupp. Watch for it later this year!