Historical Hypotheses Give Students Choices

“Which would you rather visit, Dull or Boring?” I asked my 8th grade students during one of our virtual interest-building polls. “The answer just might surprise you,” I added.

Most of them said they were “undecided” and thinking they would not want to visit either. The reason was obvious – until they learned that Dull, Scotland (pop. 80) and its sister US town Boring, Oregon ( pop. 800) were actually teaming up to boost tourism and interest in their rather obscure locales.

How amazing for my 8th graders to learn for the first time that, in fact, Dull and Boring were more than just a cultural cliché in social media. Dull and Boring were a phenomenon that spanned two continents! Who knew?

Setting the Learning Stage

The post COVID-19 world will continue to challenge every aspect of our educational think tank: from reevaluation of our current educational practices to reexamining how we develop meaningful relationships with our curriculum, our students and their families, and the real world.

While our teaching approach going forward may look quite different, some things in our “new normal” education world will remain the same. And one of the most significant – especially for middle schoolers – is the need to establish opportunities for stimulating and compelling inquiry.

So how can we use the lessons learned from our COVID teaching best practices to reintroduce our in-person students to the “new world” of inquiry immersion? Here’s a key strategy of mine I’ll be carrying over in the new school year.

The Historical Hypothesis

How do we help students jump the gap between regular “classroom practice” and meaningful, relevant historical interconnectedness? I use what I think of as “sparks of engagement” – in this case the Historical Hypothesis. (If you were thinking that a “hypothesis” is just for Science Lab, read on and think again.)

In my class, the real world connection between Dull and Boring was more than just a simple tale of two little towns. It became the spark of inquiry for our study of American expansion, mimicking the geographic significance of relationships created during America’s Age of Imperialism in a simple and accessible way for adolescents.

After my students observed the data collected during the class PearDeck poll we conducted in real time, they were automatically drawn into our work. Upon digging deeper and realizing that these two cities not only actually existed, but were also socially, economically and historically connected, students began to reevaluate their responses to the possibilities of Dull and Boring.

This set up our prediction stage and the beginning of an intellectually stimulating conversation about how America’s interconnectedness with other countries and continents impacted the Age of Imperialism:

This Is How It Works

This Is How It Works

HYPOTHETICAL AIM: “How has Imperialism changed and challenged America?” By offering them an open-ended compelling question, students are allowed to make a determination (devise an initial hypothesis) and share what they believe to be true about the question or topic based on the amount of information that they currently have.

OBSERVE: Students are then asked to complete a task in order to carry out observations and collect information about the question through our structured framework – utilizing various resources, such as audio, video, or authentic written primary source documents.

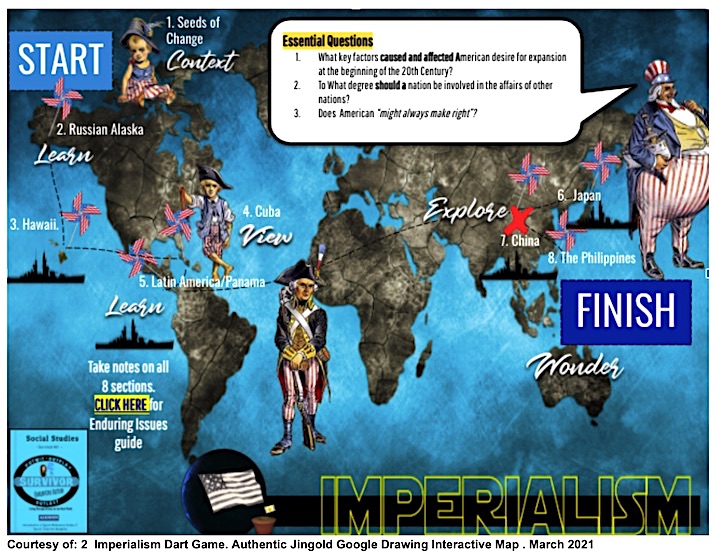

In my class, choice board maps, such as the one for Imperialism below, are very common. They are visually appealing for all learners while providing both repetition and continued practice with the basic foundations that students need in order to fully understand – in this case – how America “grew up” and matured on the global stage.

The presence of essential questions also continues to remind students how to approach analyzing each source highlighted on the map.

ANALYZE: Students then review and re-evaluate their newly collected “evidence” in order to try to prove their projected hypothesis, while being encouraged to “go where the evidence takes you.” At this point, students have collected information that either supports or disproves their hypothesis.

Over time, this part of the process not only allows students to better articulate their thoughts about what they believe to be true, but also allows them to gain a greater appreciation for the alternate viewpoints of those they might disagree with. Analysis is done both individually and as a group to encourage appreciation for multiple perspectives.

EVALUATE: Historical Hypotheses are designed so that teachers are never telling students what to think. Rather, they promote the idea of teaching all students how to better think for themselves. Students’ self-evaluation of their own initial hypothesis and repeated consideration of multiple viewpoints are both essential to developing a growth mindset. Some students find that their original conclusion was justified, while many others change their mind based on their findings.

Using the Power of Provocation

The highlight of the learning experience is the post-lesson poll that asks students to take a position, such as this: “American expansionism did create a BETTER interconnectedness between THE U.S. and the rest of the world.”

Their hypothesis has now become a full fledged claim, which is either supported or refuted by the evidence collection.

For the vast majority of students, I typically see a transformation throughout the year as they become accustomed to posing and exploring hypotheses. Students often become empowered by understanding how to do this. Their conclusions are formulated, while also being intellectually challenged. Their ability to acquire information gives them options.

Those students who initially could only identify with their own viewpoint find themselves able to see, identify with, and appreciate other viewpoints. Often students witness their classmates changing their minds in real time as they listen intently to the powerful conversations that occur as a result of this process.

In education this is the “Power of Provocation.” Provocation presented in this way becomes an open ended activity designed to stimulate ideas and imagination rather than to simply lead students by the nose to accepting a prescribed outcome.

It lets the student choose – and lets them see they are really making the choice. And, for a middle schooler, that’s HUGE!

Jennifer Ingold (@msjingold) was chosen as both the NCSS and NYSCSS Middle School Teacher of the Year in 2019 and has received the Cohen-Jordan Secondary Social Studies Teacher of the Year Award from the Middle States Council for the Social Studies.

Jennifer currently teaches eighth grade social studies at Bay Shore Middle School in Bay Shore, New York. She has been a speaker at local, state, regional and national conferences, is a lead blogger for C3Teachers.org, and has had her work featured in major publications such as Social Education, Middle Level Learning, and AMLE Magazine.