Good STEM Teachers Never Stop Learning

A MiddleWeb Blog

I’ve had plenty of time to reflect recently as I recuperate from a fall that injured an eye and broke my foot. (Everything is improving.) Here’s what’s rolling around in my head presently.

I’ve had plenty of time to reflect recently as I recuperate from a fall that injured an eye and broke my foot. (Everything is improving.) Here’s what’s rolling around in my head presently.

In the beginning . . .

I wish I could start my teaching career all over, knowing what I know now. How differently I would teach from the very first day.

I should tell you that when I started teaching, I’d never taken an education course. I’d certainly never heard of project learning or STEM, with that all-important “Engineering” component in the middle.

Without going into detail, I was snagged from a rewarding career in virus research to teach 7th grade math for a year. I remember naively thinking: Okay, how hard can teaching 7th grade math be?

Oh, it was hard, all right! Especially when I realized my job was not to teach math; I was supposed to teach students math. Wow! That’s a game changer!

By the end of the year I realized that this was how I wanted to spend my life – helping students learn and grow. I took the required courses to get certified in secondary science and eagerly launched into a new career as an 8th grade science teacher.

I made mistake after mistake as I plunged in gung-ho. I taught in the same way my teachers taught me. Students in straight rows. No talking. Teacher lecture. For “exciting” lessons, add class discussion and an overhead projector. Stick strictly to objectives in the pacing guide.

My students had little say in what they learned or how they learned it. My assessments consisted of traditional written tests, and lab experiments were mostly canned. I shudder when I think about it. Looking back, I could have written a book on ways to shoot down effective classroom learning.

The one thing I did right

Probably the main thing I did do right was care about my students with all my heart. I wanted them to do well, and I really loved those peculiar, mysterious, amazing middle schoolers. They responded well and we had good relationships – at least from my perspective. But despite my best efforts, I didn’t have time to spend with them individually.

I taught 180 students a day, not counting homeroom. My classes were packed full, I taught six periods, and I monitored hallways in between. We were in an un-airconditioned classroom in an old school. I soon figured out that sitting in rows and fidgeting in the Alabama heat while the teacher droned on couldn’t be the best solution.

Becoming a teacher AND a learner

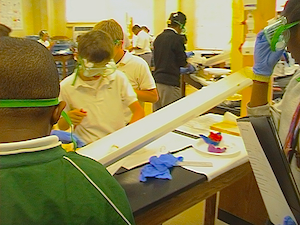

Undaunted (mostly!) by the less-than-optimal situation, I zealously began making changes. I swapped out my classroom desks for tables and let kids sit in pairs. I cleaned three decades of dust off old lab items stuffed in a school closet, and begged and borrowed other manipulatives.

After diligent research (in those pre-PLN days) I began to set up attention-grabbing demonstrations. To the extent I had enough supplies, I involved students in investigations and experiments.

Along the way I did some things right that I’d like to share with you.

During the process . . .

►I turned to colleagues for knowledge and support.

Other science teachers in my school and in other schools in the district gladly helped. We got together periodically and exchanged ideas, then developed engaging lessons and tested them in our classrooms. We wrote up successful lessons and shared them widely with other teachers in our system.

We even conducted workshops for beginning science teachers on weekends. The best practices I discovered over the years came from our collective efforts. All of us wanted to be the teachers our students needed.

Since students had a long history of working independently and competitively, this was not a smooth adjustment. They needed consistent guidance on how to care about one another and interact productively to tackle lesson challenges. I studied everything I could about teaming and gradually developed ways of helping them work more collaboratively and help one another be successful.

►I started centering lessons around the big ideas from the course of study.

At that time, our state and district courses of study featured lengthy, detailed lists of science content objectives. As I gained more experience, I realized that when students delved deeply into a topic they processed and remembered it better. So I focused lessons on important core ideas from the curriculum and brought in some other objectives if appropriate.

This involved some risk. Since the mind-boggling lists of objectives generally derived from standardized test content, I had to make a decision. Should I prepare students for “the test” or prepare them with deeper knowledge and competencies? You can guess what I decided. (Oddly, it seemed to improve their test scores.)

►I redefined success.

Two things reinforced my resolve to be an effective teacher: (1) Small successes energized me and spurred me onward. (2) Mistakes merely fueled my motivation to try again and get it right.

Epiphany! If my students cared about accomplishing a challenge, they should be anxious to try again when they failed – if they were in a “safe” learning environment. (At that time students’ academic success depended on scores on written tests and activities.)

I introduced the idea of productive failure in my definition of student success and congratulated students on their opportunities to learn from what didn’t work. Students eventually relaxed and began focusing on getting better results.

►I began taking more time to build student understanding and know-how before introducing new tasks.

Quick example: My classes were studying factors affecting crop growth so I placed containers of soil, seeds, vinegar, water, measuring equipment, etc., on students’ tables. Without further instructions I told each team to design and conduct an experiment to determine how acid rain affected crops. Students were bewildered: What do you mean? How do we do that? Just tell us what to do! May we just answer the questions at the end of the chapter?

I wasn’t prepared for so much pushback and confusion. In one of the sloppiest science lessons I ever conducted, filled with heavy coaching, teams managed to come up with ideas and figure out doable ways they might test them. Weeks later most teams had some results. Then I asked: Okay, what are you going to do with these results? What problems with crop growth did you notice, and how can you use your results to help find solutions?

Most students looked dumbfounded. I had helped to create this bewilderment by previously presenting them with mostly cookie-cutter investigations. Ergo – they weren’t thinking for themselves, recognizing problems, and designing their own solutions.

Figuring out how to guide students to be thoughtful, creative, collaborative, and enthusiastic learners proved hard! Heck, teaching proved hard! The challenges sometimes seemed insurmountable, but I maintained my quest to find answers. I loved this job, my students, and sincerely believed that teaching was the most important thing I could do with my life. I still believe that.

At the conclusion . . .

On my last day as a full-time classroom teacher, I thought back with longing over the years of improving my craft. I knew I could still learn more and be a better teacher for my students, given emerging new tools, opportunities, and teaching strategies. And I still wanted to do that!

Maybe that’s a hallmark of true teachers – we’re never satisfied.We crave more information and ideas and jump at opportunities to expand our toolkit. That leads me to this bit of hard-won wisdom:

Take it one small step at a time. As you teach, focus on small successes. Don’t try to change everything at once. When discouraged, just keep pushing forward one small step at a time. You’ll be astounded at how much your capabilities increase throughout your career and your life.

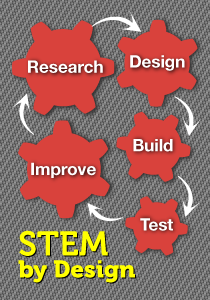

During my career, teaching steered me in astonishing directions and connected me with incredible people. If STEM had been on the radar in my earlier teaching days – if I had entered my teaching career with some STEM principles, skills, and knowledge – I would have started teaching with so much more comfort, creativity, and understanding.

You have that opportunity! Go for it!