5 Kinds of Nonfiction: A New Way of Thinking

A new and useful framework for thinking about nonfiction in the classroom.

By Melissa Stewart & Marlene Correia

When Marlene reviewed library data for one of the middle schools she works with, she found that sixth grade students were checking out very few nonfiction titles. That surprised her.

By asking the students some questions, Marlene discovered that most of the books students were checking out were being used for a book talk assignment – and the teachers’ list of suggested titles included no nonfiction.

Once teachers let their classes know they could choose a nonfiction title for their book talk, students began checking out more nonfiction.

Nonfiction often takes a back seat

Marlene’s story is just one example of a problem we encounter time and again. So often educators favor fiction for read alouds, book talks, book clubs, classroom instruction, and special assignments. They seem to believe that young readers prefer fiction, and yet, here’s what students are actually saying:

“I like nonfiction because you gain knowledge. Then you ask more questions.” (Asher, fourth grader)

“Nonfiction is better than fiction because it has real, helpful facts about life.” (Kelsey, fourth grader)

“I like that nonfiction books really make you think about things for a while and then sometimes your thinking changes.” (Ryan, fifth grader)

And, really, why should comments like these be a surprise? In the adult publishing world, nonfiction sales are strong because when readers have the power to select their own books, they often choose nonfiction.

Humans love facts, stats, ideas, and information. It’s what makes the TV show Jeopardy! so popular, and it’s the reason the Guinness Book of World Records is a bestseller year after year.

In addition, wide-ranging research clearly shows that many students enjoy nonfiction as much as or more than fiction (Barnes, Bernstein, & Bloom, 2105; Correia, 2011; Doiron, 2003; Mohr, 2006; Pappas, 1991; Repaskey, Schumm, & Johnson, 2017). And for some of these children, nonfiction is the gateway to literacy (Caswell & Duke, 1998; Hynes, 2000).

Studies like these led Heather Simpson, Chief Program Officer for Room to Read, to pen an article entitled “Children Want Their Nonfiction Books, Adults May Be Their Barriers” for Medium. “A child learning how to read with fiction texts alone misses a unique opportunity to pique an independent interest in reading,” argued Simpson.

And yet, despite all this evidence, many educators continue to have misconceptions about the reading preferences of the students they serve. Why is that?

It may be that teachers who prefer fiction themselves assume that students have the same taste. They may also have dreaded memories of stodgy textbooks and uninspired survey titles from their own childhoods. And perhaps they aren’t aware of the incredible array of nonfiction books available today.

Nonfiction is growing and changing

As Publishers Weekly recently reported, both middle grade and young adult nonfiction works are more diverse and innovative than ever before, and the same is true for books for younger children. Indeed, experts agree that we’re in the midst of a golden age of nonfiction.

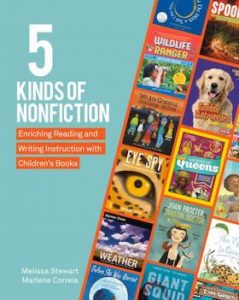

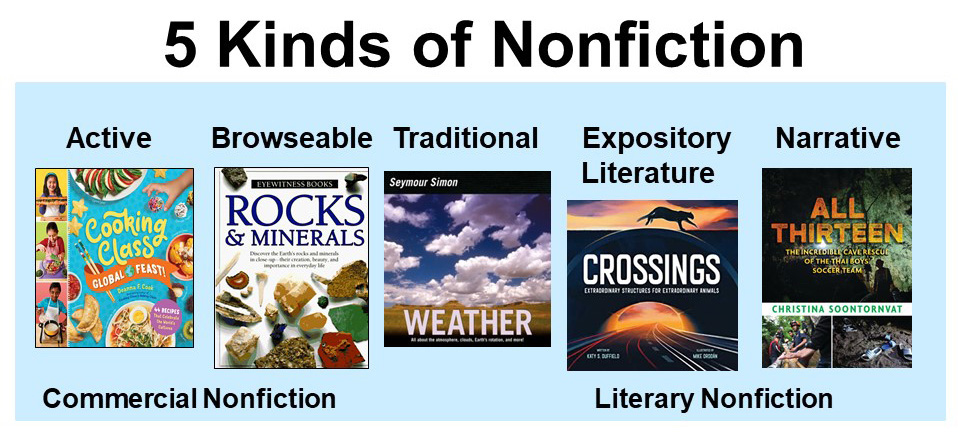

To help students (and educators) make sense of the wide world of nonfiction, we advocate the 5 Kinds of Nonfiction classification system—active, browsable, traditional, expository literature, and narrative.

When students understand the characteristics of these five categories, they can predict the type of information they’re likely to find in a book and how that information will be presented. And that allows them to quickly and easily identify the best books for a particular purpose (early stages of research, later stages of research, mentor texts in writing workshop, etc.). They can also recognize the kind of nonfiction books they enjoy reading most.

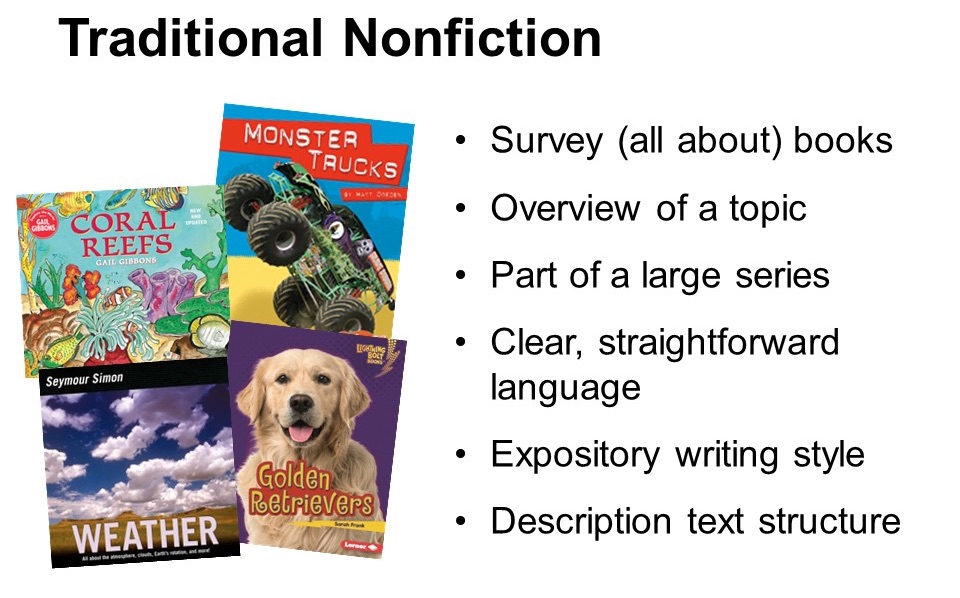

✻ Traditional Nonfiction ✻

✻ Traditional Nonfiction ✻

Not long ago, there was one just kind of nonfiction for children—survey (aka “all-about”) books that provide a general overview of a topic. These traditional titles, often published in large series, emphasize balance and breadth of coverage and feature language that is clear, concise, and straightforward. They have an expository writing style that explains, describes, or informs, and typically employ a description text structure.

As a result of advances in book production, these books are now more visually appealing than they were in the past. And because they provide a broad introduction to a topic, they’re ideal for the early stages of the research process, when students are “reading around” a subject to find the focus for their report or project.

The straightforward, age-appropriate explanations make the information easy to digest, which is helpful to students who are just beginning to learn how to synthesize and summarize information as they take notes.

✻ Browseable Books ✻

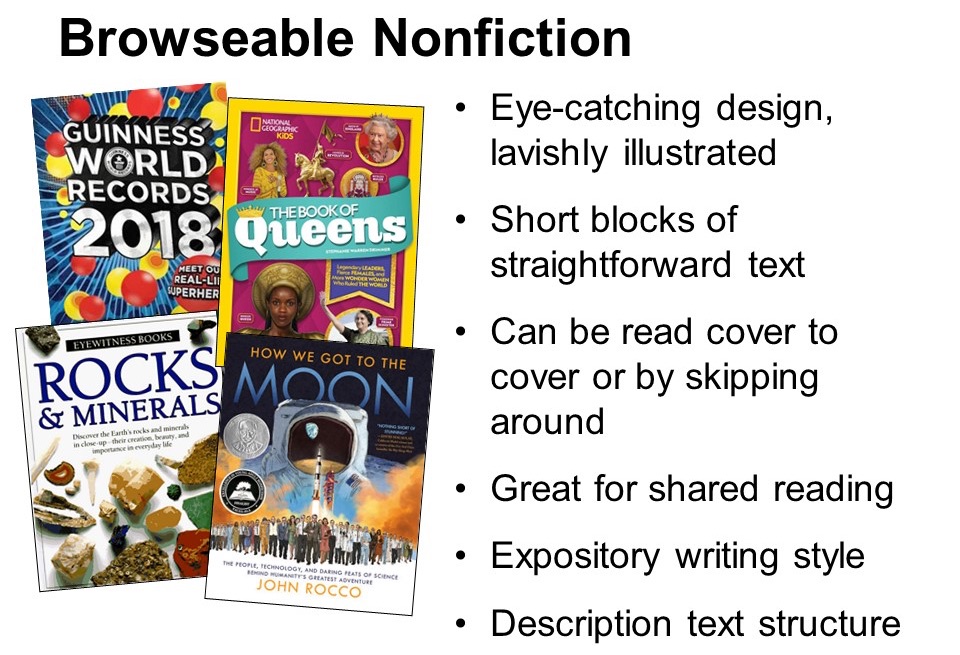

Thanks to Dorling Kindersley’s innovative Eyewitness Books series, the 1990s brought remarkable changes to traditional expository nonfiction. These beautifully designed, lavishly illustrated books with short text blocks and extended captions revolutionized children’s nonfiction by giving fact-loving kids a fresh, engaging way to access information.

Readers can easily dip in and out of browseable books, focusing on sections that interest them most, or they can read the books cover to cover. Today, many companies publish fact-tastic books in this category, and kids love them.

Due to their wide array of text features, browseable books are well suited for the later stages of the research process, when students are seeking specific information and looking for tantalizing tidbits to engage their audience of readers.

✻ Narrative Nonfiction ✻

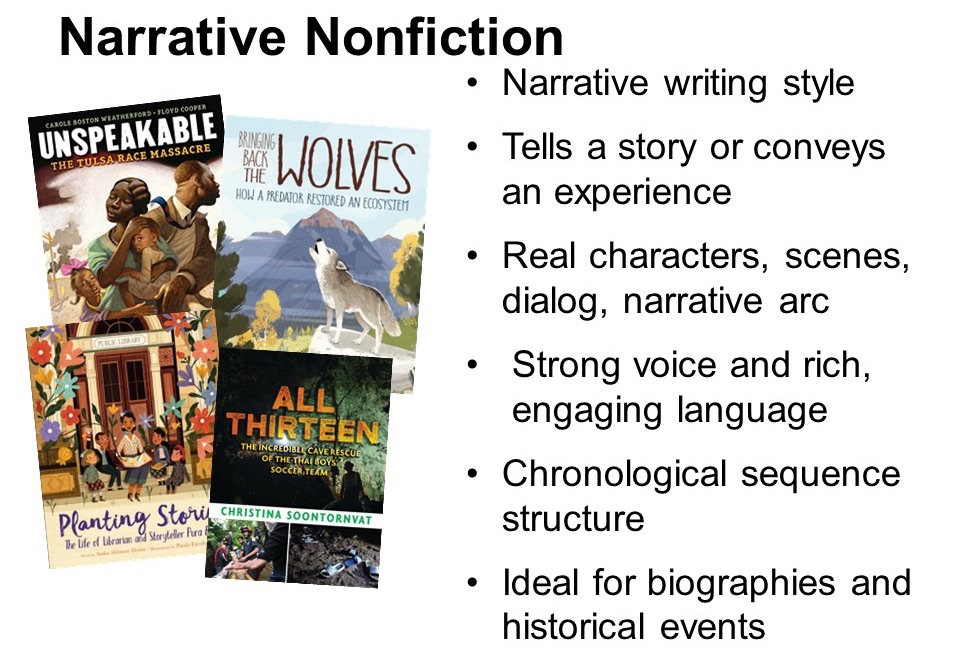

In the mid-1990s, children’s authors began crafting narrative nonfiction – prose that tells a true story or conveys an experience. Narrative nonfiction appeals to fiction lovers because it includes real characters and settings; narrative scenes; and, ideally, a narrative arc with rising tension, a climax, and denouement.

The scenes, which give readers an intimate look at the events and people being described, are linked by transitional text that provides necessary background while speeding through parts of the true tale that don’t require close inspection.

Narrative nonfiction, which typically features a chronological sequence text structure, slowly gained momentum during the 2000s. Today, it’s the writing style of choice for biographies and books that focus on historical events. It may also be used in books about animal life cycles or scientific processes, which have a built-in beginning, middle, and end.

Because narrative nonfiction titles often lack headings and other text features, they aren’t as useful for targeted student research as other kinds of nonfiction, but they can help young readers get an overall sense of a particular time and place or a person and their achievements.

✻ Expository Literature ✻

When Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, school funding priorities suddenly shifted. School library budgets were slashed, and many school librarians lost their jobs. Around the same time, a national economic recession threatened public library budgets too. By the mid-2000s, the proliferation of websites made straightforward, kid-friendly information widely available without cost, which meant traditional survey books were no longer mandatory purchases for schools or libraries.

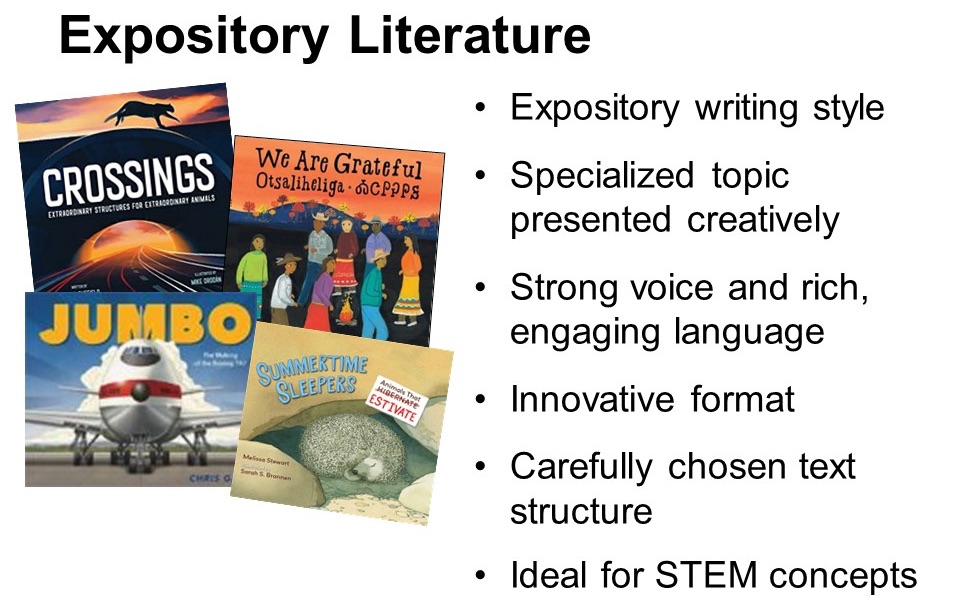

As nonfiction book sales slumped, authors, illustrators, and publishers searched for ways to add value to their work, so they could compete with the Internet. The result has been finely-crafted expository literature that delights as well as informs. Unlike traditional nonfiction, expository literature presents narrowly focused or specialized topics, such as STEM concepts, in creative ways that reflect the author’s passion for the subject.

Besides being meticulously researched and fully faithful to the facts, expository literature features captivating art, dynamic design, and rich engaging language. It may also include strong voice, carefully chosen text structure, and purposeful text format. These characteristics make expository literature an ideal choice for mentor texts in writing workshop. These books can also help students recognize patterns, think by analogy, and engage in big picture thinking.

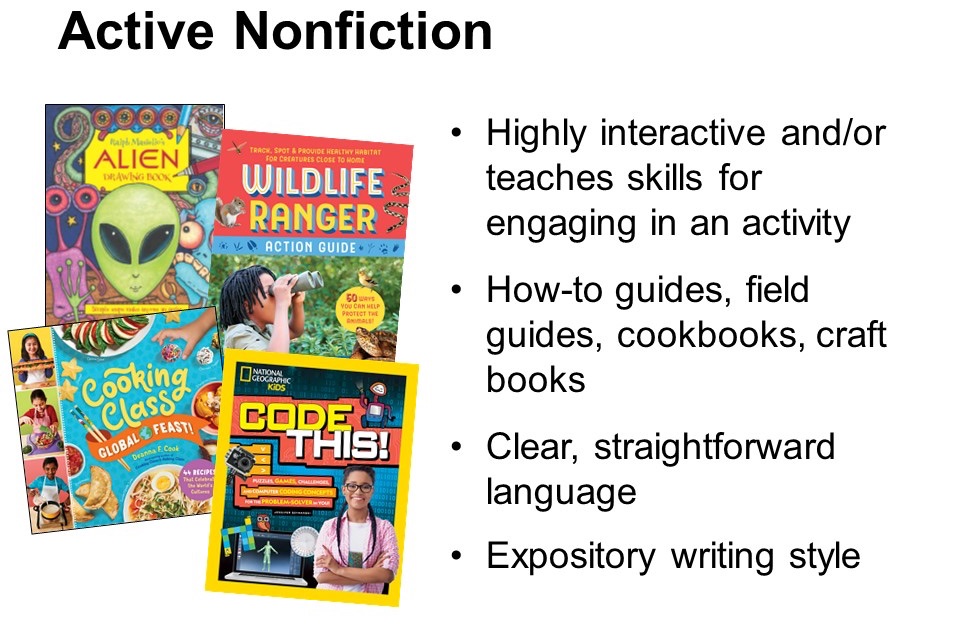

✻ Active Nonfiction ✻

Active nonfiction has been around since at least the 1980s, but thanks to the maker movement, these books have hit their stride in recent years. Active nonfiction is highly interactive and/or teaches skills that readers can use to engage in an activity.

Written with an expository writing style, these field guides, craft books, cookbooks, books of scientific experiments, book-model combinations, etc. are richly designed and carefully formatted to make the information and procedures they present clear and accessible. These books, which are currently extremely popular with young readers, are the perfect addition to school and library makerspaces. In many cases, they are also ideal mentor texts for procedural writing.

Class Activity

Introducing Students to

the 5 Kinds of Nonfiction

Organize students into small groups and invite each team to gather a variety of nonfiction books on a single topic from the school library. After the children have sorted the books into at least three categories that make sense to them, compare the criteria each group used.

Next, introduce the 5 Kinds of Nonfiction classification system and share a set with books on the same topic that fit into each category. After reading aloud sections of each book, ask students to compare how the books present information. Is the focus broad or narrow? What kind of text features, text structure, writing style, and craft moves does the author use? Does the writing have a distinct voice? What similarities and differences do students notice across the categories?

Finally, send students back to the stacks to gather a selection of nonfiction books on a new topic. Invite each team to sort the books into the five types – narrative, expository literature, traditional, browseable, and active. Did they find examples of all five kinds of books? If not, can they explain why?

Nonfiction in Your Classroom

Take a moment to evaluate your classroom book collection. Do you have enough nonfiction titles? Experts recommend a 50-50 mix of fiction and nonfiction. Do you have a healthy selection of books from all five categories– active, browsable, traditional, expository literature, and narrative?

Now think about your instruction. Do you tend to focus your reading and writing lessons around fiction? When you select informational books for read alouds, book talks, or mentor texts in writing workshop, do you usually choose narrative nonfiction?

If you find yourself favoring fiction and narrative nonfiction, you aren’t alone. Many educators connect strongly with stories and storytelling. And it’s natural for them to assume that young readers feel the same way. But this is a bias we must learn to recognize and address. Let’s celebrate all the different kinds of nonfiction and the kids who love it!

Dr. Marlene Correia is an Assistant Professor of Literacy Education at Bridgewater State University. Marlene has 30 years of education experience as a K-8 classroom teacher, district administrator, and teacher educator. She is a past-president and current board member of the Massachusetts Reading Association.

The teachers at our school follow the Units of Study program. My understanding is that this program is quite specific about what students are supposed to read and when. 8th Graders start the year with a unit of Literary Non-Fiction, which is an area that clearly needs additional Library and classroom collection development as I had to redirect a number of students to the OverDrive collection of the local Library so they could choose something that interested them.

We only have one copy of books such as I Am Malala and Radium Girls. I am noticing that our 6th graders in particular are asking more for non-fiction for their personal reading as they get to know the Library better. I am also currently doing a deep weed of the non-fiction section and I can see the changes you describe over the past twenty years, in our collection. However we have very few Narrative NonFiction books.

Thank you for writing this – it helped me think more about how Non-Fiction is structured for middle graders.