GRR: Who’s in Charge? Teacher or Student?

A MiddleWeb Blog

John Hattie’s research puts student willingness to “own” learning near the top of success indicators. But how do we get them there? GRR is a key strategy. In a year-long series, two literacy coaches explore ways to make Gradual Release of Responsibility part of everyday practice.

By Sunday Cummins and Julie Webb

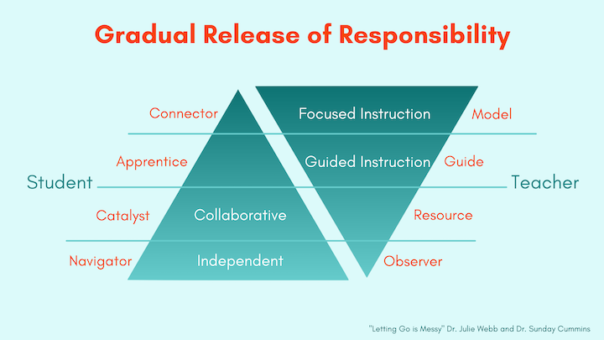

In truth, though, we want students to be in control of their learning. GRR (or whatever you decide to call it) is about a partnership between the student and the teacher – a partnership that is driven by the student’s strengths and needs as well as by their engagement in the process (Gaffney and Jesson, 2019).

We are looking forward to expanding on this idea in future blog posts, but to start we’d like to shed some critical light on what this shared responsibility for leading the learning process looks like at different points of the gradual release of responsibility.

Student as Connector, Teacher as Model (“I DO”)

The focused instruction phase of GRR is when a new type of strategic processing is introduced, reviewed, or clarified. (The focus is determined by what the teacher has noticed as they observe students during previous “you do” learning opportunities.)

This phase frequently involves the teacher providing explicit instruction that includes declarative knowledge (“what” the strategy is), procedural knowledge (“how” to employ the strategy), and conditional knowledge (“why” and “when” to use the strategy). The latter occurs during a demonstration or think aloud. (We plan to explore this further in upcoming post).

What’s key here is that the students are FULLY engaged during this phase (which makes the phrase “I do” potentially misleading). Ideally the teacher begins by engaging the students in some way, helping the students notice an aspect of their learning that may need support, and making relevant to the student the strategic processing that is going to be explained.

Then as the teacher demonstrates that type of strategic processing, the student can make connections between what they do and do not already understand, listening and observing with intent. They can improve their chances of success by thinking metacognitively about how they can apply the knowledge and skills their teacher has focused on during this phase of instruction.

Student as Apprentice, Teacher as Guide (“WE DO”)

During this phase students “give it a go,” attempting to apply the strategic process that has been introduced and demonstrated, with the teacher fully present as a guide. Students ask questions to clarify their learning, embrace the risk-taking and messiness that comes with trying something new, knowing the teacher is there as a guide when they falter.

The teacher hosts this space. This may include choosing excerpts of text for the students to grapple with or creating tasks for students to begin to apply the strategic processing that was introduced during the interpreter-modeler phase of GRR.

The role of the teacher during “we do” is to anticipate points where students will likely need assistance, to observe students at these points, and to be ready to offer feedback and scaffolds that match the needs that students reveal.

Student as Catalyst, Teacher as Resource (YOU DO IT TOGETHER)

There’s a great deal of learning to be gained when students collaborate with a common purpose. One of the biggest benefits of collaboration is the increased awareness that comes from listening to the different perspectives of their peers.

In a safe learning environment, our students have much to offer one another (not to mention their teachers), and their unique ways of knowing and doing can elaborate, deepen, and extend learning far beyond what a teacher can accomplish during guided practice.

The collaborative phase offers the opportunity to take even greater risks when trying something new, knowing that a virtual safety net still surrounds them. Students can maximize peer collaboration by advocating for themselves as learners and seeking support from their peers.

The role of teachers during “you do it together” continues to be to look and listen carefully. Their observations can help them determine when to step in and offer an assist, or when to let things play out and allow students to grapple with the unfamiliar in a productive way.

Assists may be related to the strategic processing that was demonstrated and practiced already, or assists may be sharing additional strategies the group needs to continue moving the learning forward. In this way the teacher is a resource.

Student as Navigator, Teacher as Observer (YOU DO)

This phase provides space and time for individual students to apply (as needed) the new knowledge they’ve gained and the informative experiences they’ve had. They explore opportunities to apply what they’ve learned in new situations and applications. They continue to reflect on how they’re measuring up to their own goals as learners.

Teachers aren’t off the hook, though, when it comes to providing instruction and support during the independent phase. It’s a time for us to reflect on whether or not students are meeting learning goals and performance expectations. It’s a moment for considering the next big steps forward for assessment and instruction.

Release Responsibility, Assume Responsibility

As we’ve detailed in this post, teachers and students take on important roles during the GRR process. Although these roles are adopted and set aside as needed, two roles are steadfastly maintained: Teacher as facilitator of learning and student as agent of learning. And it’s vital that we don’t privilege the teacher’s perspective but instead remember the power of the teacher-student learning partnership.

If teachers understand the benefits of each phase and when to employ them, they can expertly traverse the instructional journey. And if students recognize the phase they currently occupy, they can capitalize on the learning experience for maximum benefit.

The shift from phase to phase shouldn’t be taken lightly, or done by rote, since there is so much to consider before making a move. We want to gradually and expertly release responsibility so that students will gladly and eagerly assume responsibility. And that process, friends and colleagues, is messy.

Sunday Cummins, Ph.D, is a literacy consultant and author and has been a teacher and literacy coach in public schools. Her work focuses on supporting teachers, schools and districts as they plan and implement assessment driven instruction with complex informational sources including traditional texts, video and infographics. She is the author of several professional books, including Close Reading of Informational Sources (Guilford, 2019). Visit her website and follow her on Twitter @SundayCummins. See her previous MiddleWeb articles here.