How Might We Teach a Graphic Novel Series?

In a previous MiddleWeb post, I focused on the teaching potential of graphic novels more generally and shared some examples of good text choices for the middle grades. I also demonstrate lesson steps that teachers can use. Be sure to check all this out!

In this follow-up, I highlight the possibilities of a particular graphic novel series. The Kid Beowulf books currently include four titles, and this post focuses on the most recent (August 2021) The Tarpeian Rock. Author and artist Alexis Fajardo shares a visual world of mythology, action, and adventure, with brimming creativity, color, and energy. Each book operates on all these levels, inviting readers to travel into a new world.

For the most part, there’s an intuitive nature to the ways the panels work inside each book. This is ideal for readers who may not be familiar with the process of reading a graphic novel or comic book format, which does rely on readers paying attention to both the words and images.

Because of the many layers of meaning-making in this visual form, graphic novels are ideal for reading and re-reading. As you begin to teach with graphic novels, more complex panel arrangements and layouts might be introduced in later texts.

Let’s take a closer look

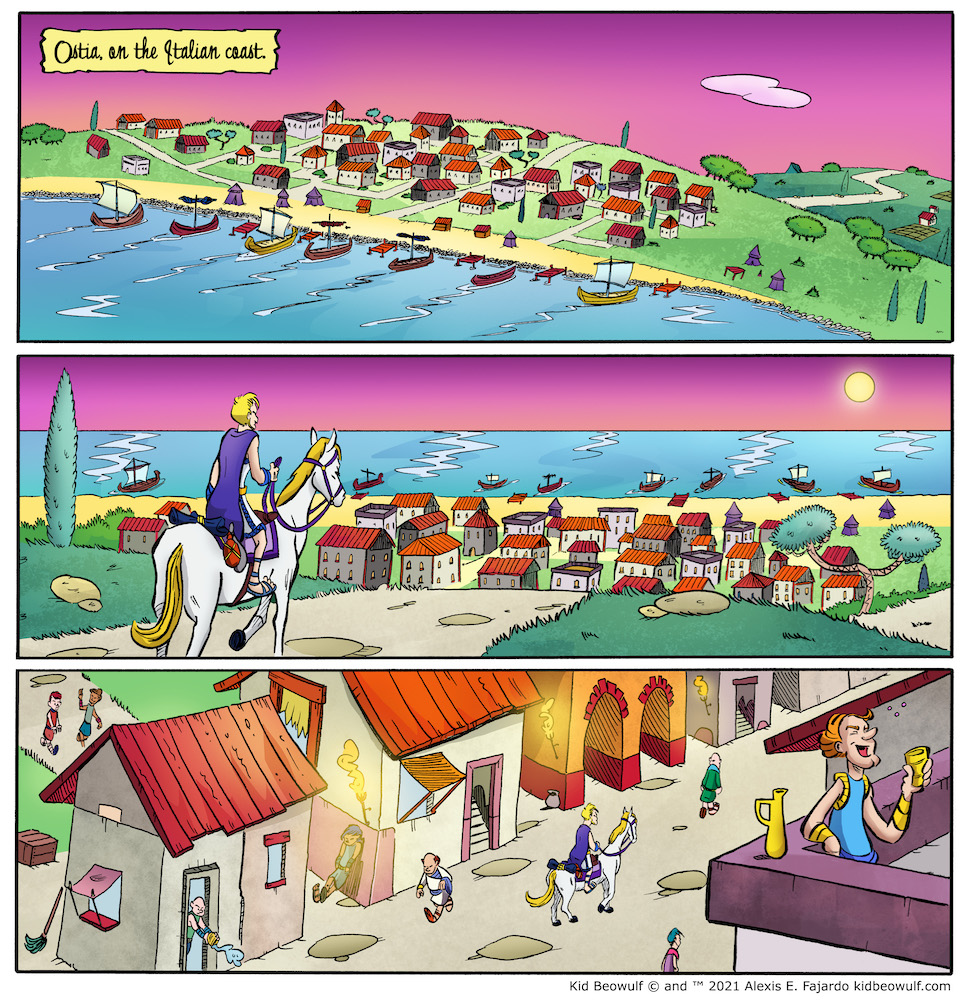

At the outset of The Tarpeian Rock, the fictional and yet grounded world of the adventure story is introduced mostly without words. A teacher who wants to maximize these panels will note first that they are arranged in a vertical series so the reader’s eye can travel down the page.

To make the most of any graphic novel, readers must savor what is on the page, in terms of words, images, and additional features, including the emotional and plot-oriented content of movement, gesture and juxtaposition, and the assumed information conveyed between panels.

The same holds true for any text we teach – a teacher lingers with the page, attending to both the words and the meaning that is created by the full affordances of the text. This is true of poetry, hyperlinked media, and traditional prose or images in film. Part of this work is conveyed in how the teacher approaches the series of questions that guide the conversation.

For example, as we view the panels in Figure 1 above (click to enlarge), I might ask, “Where are we in this story? Who do you think the main character is? What can we determine about the main character? What kind of setting this?”

Inviting conversations through these multiple prompts is not unlike a book club approach in which discussion can be co-constructed, even around a page that scarcely has any words on it. Critics of comics might suggest that the lack of words on some pages is an issue, to which I reply: that might be true if the only books you use in your instruction are comics, or if you only focus on the wordless pages without taking stock of other text-heavy graphic novels. This might also be true if the reading experience is fast-paced, passive, and does not include attention to details.

Another critique of comics might suggest that an overreliance on the images themselves may be harmful. I must agree that to read a book, we must focus on the words, as well as the additional features that the text offers. To that end, when teaching a text, I focus on everything that the author and/or artist has intended.

In the case of the Kid Beowulf series, I also have a ready stock of background knowledge to build in relationships to classic texts and historical knowledge, including the nature and role of myths in culture.

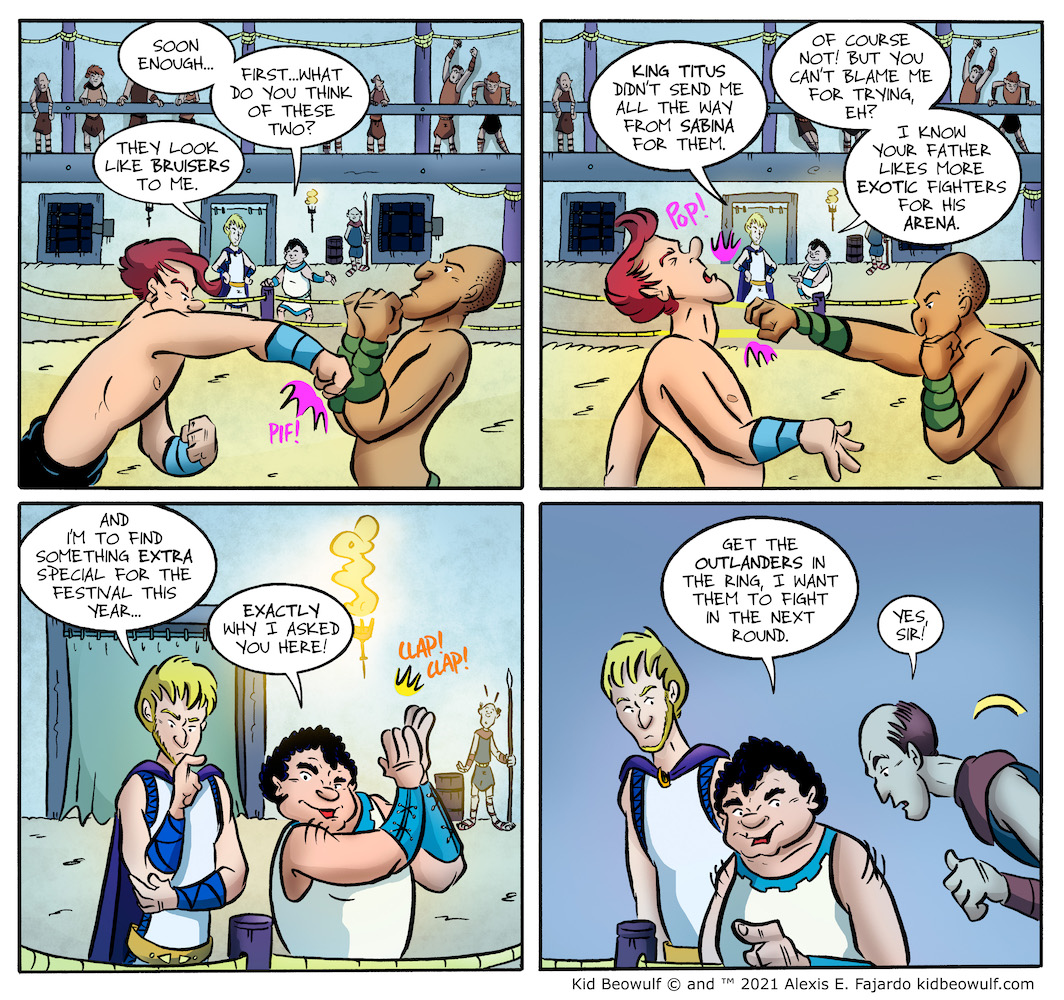

When moving to a page that includes more text and panel arrangement, I would model reading right to left, and from the top of the panel to the bottom so that all of the dialogue can be taken in, as well as the author’s choices in background images.

In addition to what is spoken, teacher questions might focus on the action portrayed in the panels, the relationships of characters, the additional features of emanata (like the claps in the bottom left panel) or other emanations of action taking place in the visual space of the panel.

In the case of the panels depicted above (Figure 2), I might dig into rich conversation about who is central to the story. Though I see two characters in the top right panel at the forefront, the real action of the story seems to focus on two figures in the background who are discussing what is happening. This is confirmed by the lower two panels. I might also draw attention to the action lines emanating from one character’s hands to depict applause and, in the bottom left panel, the action of bowing.

Going deeper into story and meaning

As a teacher who is guiding students through a journey of text, I can now ask questions related to both the words and images, including questions of the characters’ motivations, goals in the story, relationships with one another, and the development of potential conflicts.

My classical training in English/language arts instruction and my experience as a middle school teacher help me with the modeling I do, both in terms of the story’s structure and the features that the text has to offer, including pictorial elements.

I hope that this glimpse into instruction, using two pages displaying seven panels (from a book of 248 pages) is helpful as you consider graphic novels in your teaching. I am glad to be in touch for recommendations and to hear stories about your classroom work with these books. I also recommend visiting Alexis Fajardo’s website at https://kidbeowulf.com/teach/, where you can find teacher’s guides for all four books in this series.

Special thanks to Alexis Fajdo for sharing the hi-res images in this post and giving his permission to use them here.

Dr. Jason D. DeHart taught 8th grade language arts for eight years in Cleveland, Tennessee before becoming an assistant professor of reading education at Appalachian State University. After some years teaching preservice teachers, Jason returned to his “first love” and now teaches ninth graders in western North Carolina. He continues to pursue his research interests include multimodal literacy, film and graphic novels, and literacy instruction with adolescents. His work has appeared in SIGNAL Journal, English Journal, and The Social Studies and here at MiddleWeb. (Updated 2024)