For Real Conversations Get All Your Kids Talking

By Paul Bambrick-Santoyo and Stephen Chiger

Paul

It’s easy to get caught up in a lively discussion in English class; after all, that’s what we want to happen. But amid the buzz, it’s also too easy to lose track of whose voice has been sidelined.

If you’ve ever tracked student participation, perhaps you’ve noticed it: a tendency for some students to speak, while others quietly observe.

Stephen

For many of our students – especially those who are quieter, in struggle, or who whose voices have been historically marginalized – the situation has dramatic consequences. It denies our kids their rightful place in the humanities.

To see a better way, let’s visit Vy Graham’s 7th grade English class in Newark, NJ. In her room, every student has a seat at the table.

Bringing Every Student to the Table

Vy’s seventh graders are reading Frederick Douglass’s famous speech “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” A prompt at the top of the page asks them to consider, “What does Douglass want his audience to feel (and how is he creating that feeling)?”

To watch video, follow this link to Vimeo & use password: uncommon1

First, watch the scene unfold (above). As you do, consider: what do you notice about how her students prepare for discourse?

Students write silently as Vy walks between the desks. She peeks over their shoulders to review their annotations and written responses, offering both affirmation and growth feedback. The timer chimes, and Vy signals students to turn to a partner and share their responses. Soft chatter fills the room. After a few minutes of conversation, Vy brings the class together to start whole-class discussion.

In the first moments of conversation, every single student has already had a chance to write, think, and likely even get some feedback. Better yet: every single student has had a chance to talk to a peer – a critical moment to rehearse their thinking before sharing it with the class.

By the end of the conversation that follows, students have pushed and prodded each other’s ideas, allowing the teacher to maximize student talk while minimizing her own. And she made it possible with a few fast moves that any of us can add to our repertoire:

Play-by-Play:

How Vy Graham Launches Discourse

- Individually Write—Students answer an open-ended prompt that invites multiple views.

- Turn & Talk—Students share their ideas with a peer.

- Cold Call—The teacher cold calls a student to begin sharing. (This can also be done as a “warm call,” giving a student a heads-up that you’d like to hear them share.)

- Volley—Students share and build on each other’s responses with minimal intervention from the teacher.

Consider the implications of this practice for student voice. Vy’s steps go beyond involving all students or even signaling to the class that everyone’s ideas have a place in her room. By allowing students to write and think first, Vy invites her students to begin forming their ideas before they get swayed by their peers. The subtext? Everyone’s views are sought, valued, and needed.

By the time discussion starts, every student has had time to engage with the text, making it far more likely they’ll share. And Vy’s had time to read what students are thinking, so she already knows where the class is struggling and which of her students might be ready to push the conversation forward. No wonder her students are so eager to speak.

Centering Students in Discourse

Vy’s instruction reminds us that great teachers don’t dominate the conversation; they facilitate it.

If students get bogged down in one area or miss a big idea, Vy knows she can push in. But, in large measure, Vy’s students – like so many of our kids – are far more engaged by talking to each other than they are to any teacher.

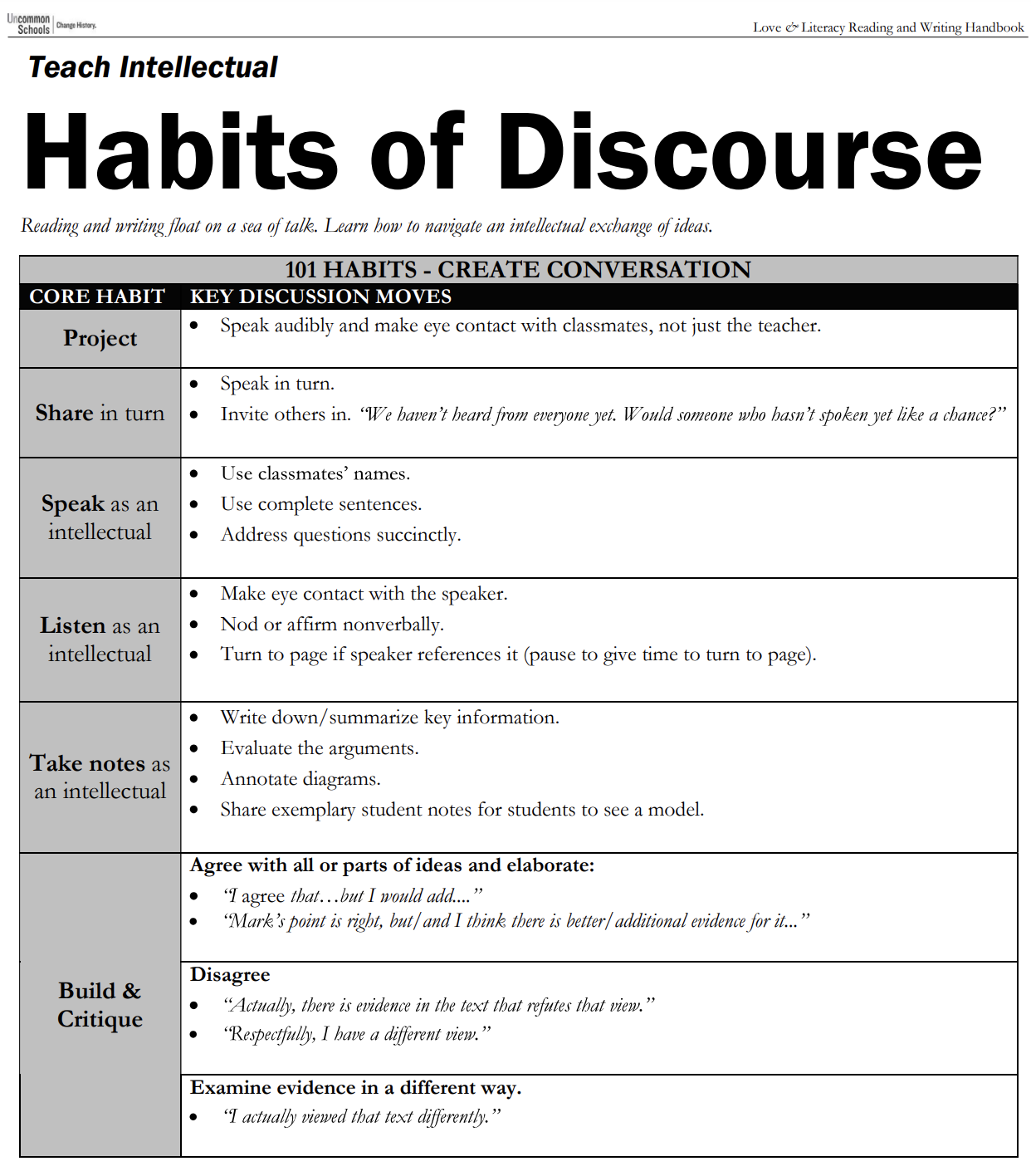

How did they reach that point? Vy’s students have adopted some “habits of discourse” – sentence starters and predictable moves that help them manage an academic conversation.

Above right is their Habits of Discourse list. It’s one shared by all the English teachers at her school (as well as the high school they’ll enter upon graduation).

Writing about this approach, our colleague Doug Lemov notes that “in most cases, good discussion skills… are not ‘naturally occurring.’” Intellectual discourse requires a different skillset than chatting in the lunchroom or after school.

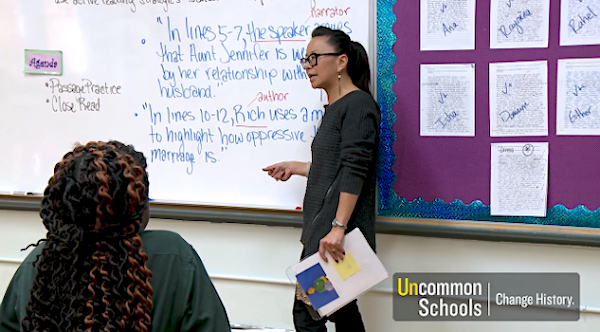

So Vy teaches the habits her students need – often directly. As you’ll see in the next video clip, the process need not be laborious. In this case, Vy wants her students to shift the way they speak about poetry (her students have been using “the speaker” and “the author” interchangeably).

As you watch, consider what moves she makes to help this new habit form and stick.

To watch video, follow this link to Vimeo and use password: uncommon1

Let’s map the steps: Vy models the skill, provides a fast practice and then keeps an ear out as students try these skills in discourse. Using this approach for the hardest new skills, it’s not long before her class has built up everything they need to self-moderate 90% of their conversations.

If you want to roll out the habits of discourse we’ve described above in your own classroom, all you’d need is Vy’s framework and a calendar. We can help with the first part: here’s the framework Vy used to help you plan.

Toward Equitable Class Discussion

Classroom discourse is an opportunity to develop one’s voice, advocate a position, and build collective understanding. Structuring discourse so all of our students experience it in full makes it equitable.

After all, it’s not really a class conversation until all your students are talking.

Paul Bambrick-Santoyo is the Chief Schools Officer for Uncommon Schools, and the Founder and Dean of the Leverage Leadership Institute. Author of multiple books, including Love and Literacy, Leverage Leadership 2.0; Get Better Faster; Driven by Data; A Principal Manager’s Guide to Leverage Leadership, and Great Habits, Great Readers, Bambrick-Santoyo has trained over 20,000 school leaders worldwide in instructional leadership.