Making the Most of GRR’s Guided Practice

A MiddleWeb Blog

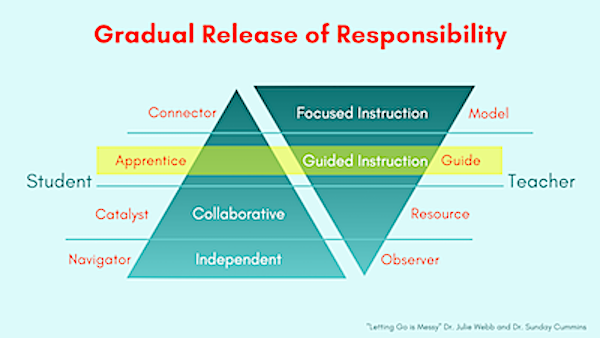

John Hattie’s research puts student willingness to “own” learning near the top of success indicators. But how do we get them there? GRR is a key strategy. In a year-long series, two literacy coaches explore ways to make Gradual Release of Responsibility part of everyday practice.

By Sunday Cummins and Julie Webb

Guided practice takes place after you have modeled a type of strategic processing of text. The students, as apprentices, work with a challenging text to make meaning, using the strategic processing you demonstrated and any other strategies they find useful.

As best you can, you provide guidance during conferences with individuals and/or small groups. If the reading work you plan for guided practice is too easy, though, the students may not learn anything. If the work you plan is too hard, they may only be frustrated.

What they need is an opportunity to engage in a productive struggle that results in learning and, just as importantly, increases their sense of agency and identity as meaning-makers.

As educators, planning for and hosting spaces for students to struggle can feel uncomfortable, murky and messy. But it’s an essential step in the GRR – in nurturing a student’s ability to learn on their own. So how can we make opportunities for guided practice more effective?

Planning for Productive Struggle During Guided Practice

Just as knowing your students and the text well helps when planning for the “I DO” part of GRR, it’s also helpful as you plan for the “WE DO.” When planning for reading instruction, this knowledge helps you pick a text (or video) or an excerpt from the source for students to practice applying a particular strategy while making meaning.

Learning only takes place when there is something new to be understood, and this causes some agitation for the learner, agitation that spurs them to slow down and think through how to strategically make sense of what they are reading or viewing.

When planning for guided and independent practice, choose texts or videos that you know will present some challenges for the students. These challenges should require using the strategic processing you have demonstrated during the “I DO” portion of that lesson or other lessons.

This doesn’t mean the entire source should be challenging. Look for “just right” sources that have some content the students can process easily and other content they can chew on.

Hosting the Productive Struggle During Conferences

Embracing productive struggle means coming to terms with the sometimes uncomfortable experience of observing a student stumble and/or fail at their first attempt to strategically process a complex text. Even harder is resisting the urge to rescue the student. We don’t want to offer the kind of support that does all of the work for the student.

It’s helpful to remember your role as “guide” during this part of GRR and the student’s role as “apprentice.” If they are truly in their zone of proximal development (ZPD) and not at the point of frustration, then they should be able to do the work with some effort.

When we lean in to confer, we can energize that work by supporting each student in a way that reveals what they can do on their own.

What the student struggles with – and how you might help – could fill several books. What follows are a few general suggestions to consider as you look to strengthen what you are already doing.

►Anticipate where students might struggle. This includes knowing the harder parts of the source they are reading or viewing. While you might confer at the point where they are in the source when you lean in, it’s also an option to ask if you can confer and think through a more difficult part. For example, Sunday conferred with several of the fourth grade students about the section on how drones may be violating U.S. constitutional rights.

►Give students the gift of wait time. Sometimes a student will hesitate while reading or discussing the source with you. This may not be because they are at a loss. They may need time to think or, even worse, they may know that if they wait, we’ll fill in the silence, we’ll jump in and help or do the work for them. If you know it’s not about frustration, our advice is to count to twenty. You might be surprised at the thinking the student reveals.

►Give yourself the gift of a pause before you respond. When a student struggles, we have to do a lot of work on the spot which includes figuring out the following:

- What is difficult about the text

- What the student’s struggle might be

- Which strategies might be helpful to offer (and these may be different than what we modeled during the “I DO”)

- How we will help the student take on that strategic processing (i.e., which questions we can ask, reminders we offer, modeling we can do).

We may also feel pressure to respond quickly. The truth is, giving yourself a moment to think and then responding in a thoughtful way (whether it’s to gather more information or offer support) has more generative value than jumping in too quickly.

►Less is more. During guided practice students may demonstrate several needs at once. During your pause before responding, consider what type of strategic processing will give them the most leverage. What can you offer that’s just enough to move them forward? That’s not so overwhelming or too much for them to retain and try again when you move on? Mindful of the cognitive load on the student, we can offer comments, prompts, and think-alouds that should be tight and concise.

►Be okay with muddling through. If you are attempting some of the shifts we’ve discussed and feel like you’re “kind of sort of” making a difference for that student, that’s appropriate as you are experiencing your own productive struggle! The student may be feeling the same way about the strategic processing they have done in partnership with you – like they sort of understand what they did. Talk about this with them. Remind them that mastery takes time and you will be providing other opportunities for guided and independent practice.

When Is the Struggle Too Frustrating?

What if we’re not sure the struggle is within a student’s ZPD? How do we know it’s a frustrational struggle? This is hard to describe. If a student struggles after you have provided some helpful reminders and/or after you have modeled with a think-aloud, the source or that part of the source may be too hard. If you end up explaining most of the content and the student doesn’t successfully or semi-successfully begin to do their own strategic processing, the source may be too hard.

Guided and Independent Practice Over Time

Students cannot be expected to master making sense of challenging sources after one opportunity for guided practice. They may need multiple opportunities for “WE DO” and “WE DO TOGETHER” as well as opportunities to self-select challenging material to make sense of on their own.

The beauty of GRR is that it’s not linear. If you feel like you need to model again, move back into acting as the model. If you feel like students are starting to make better sense of source(s), nudge them into navigating their own learning while you observe from a distance. Then watch for what they might need next and plan and implement the cycle of GRR again.