Student-Created PSAs Ignite Critical Thinking

Which of the following is not a topic covered by one of the “non-commercial” TV commercials known as PSAs?

Which of the following is not a topic covered by one of the “non-commercial” TV commercials known as PSAs?

Texting While Driving. Childhood Hunger. Bullying. Climate Change. Seatbelts. Forest Fires. Drug Abuse. Ocean Pollution. Autism. STEM. Retirement. Alzheimer’s. Coronavirus. Drunk Driving.

As you probably guessed, they’re all subjects of public service announcements (PSAs).

One of the largest producers of PSAs in the US is the Ad Council. More than likely you’ve seen their logo embedded in a print or internet ad or on television. On their website you can find many examples of their campaigns. To see the latest, check the Ad Council YouTube channel. Here’s one about Women in STEM.

I started to incorporate PSAs into my media literacy workshops after seeing one of the national TRUTH anti-tobacco spots. The TRUTH campaign, aimed at young people, was a result of the 1998 federal tobacco settlement in which millions of dollars flowed into states. The TRUTH site is still going strong with a current focus on avoiding or giving up vaping.

Soon after seeing these professional produced spots, many educators had their students create their own. A colleague sent me this—his student’s anti-tobacco PSA—in the style of Animal Planet’s Crocodile Hunter.

Why PSAs Are Important

More than likely you have seen, heard or read a PSA on television, on the radio, or in a newspaper or magazine. But what about your students? Would they know what these unique messages are designed to do?

The organization Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance) reminds us: “PSAs encourage students to create messages of action and raise awareness of social issues. This task moves students from passive forms of social action (‘liking’ something on Facebook or commenting on YouTube) into active use of multimedia to effect change.” (Source)

Smokey Bear ads, credited with saving millions of forest acres, first appeared in 1944. Read the history.

I was recently invited by a middle school teacher to introduce her students to Public Service Announcements. As a media educator, my goal is always to engage my audience (teachers and students) in both analyzing AND making media messages.

Working with their teacher, we agreed that I would introduce the topic during one class period. The students would work for a week, and I would return a week later to view their finished productions.

Their teacher admitted that her students knew little, if anything, about the subject so I suggested some background articles for them to read prior to my arrival. Here are two for your consideration:

After being introduced to the students, I decided to start from scratch—and I began with this definition:

PSAs are “a message in the public interest disseminated without charge, with the objective of raising awareness of, and changing public attitudes and behavior towards, a social issue.”

I explained that PSAs are ads but they’re not selling a product.

Next, I defined “social issue,” thinking these students might need clarification:

“A social issue or problem is an issue that has been recognized by society as a problem that is preventing society from functioning at an optimal level. It’s important to understand that not all things that occur in society are raised to the level of social problems. Four factors have been outlined that seem to characterize a social issue or problem.“ (Source)

Next, I reviewed the four factors:

- The public must recognize the situation as a problem.

- The situation is against the general values accepted by the society.

- A large segment of the population recognizes the problem as a valid concern.

- The problem can be rectified or alleviated through the joint action of citizens and/or community resources. (Source)

I went around the room asking students to brainstorm and then name a “social issue.” Some had answers right away, others struggled. One student said the “pot holes” in his neighborhood was a social issue. I referred to the “four factors,” and we discussed whether pot holes were something a large segment of the population recognizes as a valid concern or was it more a local issue in your neighborhood?

Teaching With and By Example

First I advised the students to “simply close your eyes and listen,” after which I asked them: “what did you hear”? My goal here is to emphasize that sounds (including music) are important elements in these spots.

With that, I held up a blank 8 X 11 sheet of paper with two columns: one labeled audio, the other labeled video. I explained that PSAs are first written before a minute of video is produced. I explained to them that it would be their job to not only write a description of the ad, including dialogue, but also time it so that it is exactly 30 seconds long. I urged them to ignore the video column for the time being and simply concentrate on writing.

[Here is a student-produced PSA about “Global Warming”. Before you see their production, they take time to show you the steps they used to create the message.]

With students seated in groups at tables, I challenged them to come to a consensus about one issue they would work on for that week. Once they did, I gave them the script template for their 30-second commercial. Next, I helped them focus by asking questions like:

- what do you already know about your issue?

- what do you want your audience to know?

- where will you go to research it?

- what important information does your audience need to know?

- what will be your “call to action”?

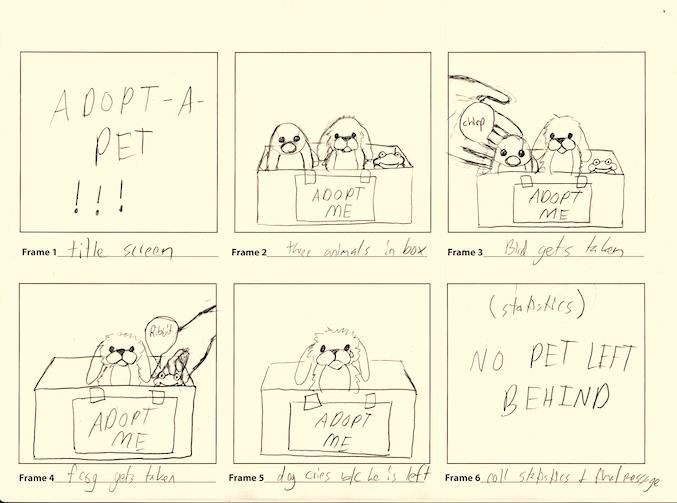

Because of time limitations, I did not introduce the idea of storyboards, but I recommend teachers include this next step. Storyboards are where artists create visual representations of what is on a script. Storyboards include “frames” which represent camera shots. I use a 6-frame storyboard. (After writing their scripts, creating a storyboard would be the next step.) In real life, producers use both the script AND the storyboard as the basis for how the final PSA will look.

Storyboards are used extensively in advertising, television and film production. Often students will tell me: “I can’t draw.” I remind them that creating storyboards is not about artistic ability, but rather it involves thinking critically about what this (something on the page) might look like. When students draw, they’re using a different part of their brains. But perhaps more importantly, they’re beginning to formulate an idea of how a “shot” in the commercial might appear. Often their camera shots will resemble the original storyboard drawing.

Judging the PSAs

Before returning, I sent their teacher a rubric for how to judge their productions. I planned to use it but decided instead to challenge the class to offer a critique of their peer’s PSAs.

After watching each PSA, I prodded them with this question: what were the strengths and weaknesses of the PSA you just watched? Rather than me playing the role of judge, they provided excellent feedback the creators could use to improve their production.

Why teach with and about PSAs?

I have thought long and hard about why an educator should devote the time to doing this project with their students. It is clear that our students are watching and learning from new platforms like TIkTok and the popularity of videos they see on YouTube. They’re being exposed to many messages, some of which may not be positive and may even be deceptive or false.

Today’s students also have unprecedented opportunities to use smartphone cameras to shoot and edit video and upload it to a streaming platform for others to see.

When I first began incorporating PSAs into my workshops, it was also clear that students do this best when they work collaboratively. And that’s valuable whether they one day become involved in collaborative enterprises like video production or simply need to be able to function well as part of a team.

The skills? They have to come to a consensus about a topic. They have to conduct research into real world problems. They have to decide if a source is reliable or not. They have to write for a purpose and they must consider questions like “What information am I going to include, and what am I going to exclude?” and “How can my words and images have the most impact on the PSA audience?”

Have you ever engaged your students in creating PSAs? What was the result? I’d appreciate hearing from you about the experience. And if you haven’t tried out this idea before but decide to dive in, let me know how it goes.

Resources for PSA Projects

Student PSAs Create Connection to Critical Issues

Public Service Announcement Rubric (International Literacy Association)

How to Create the Perfect Public Service Announcement

PSAs: A How-To Guide for Teachers

Public Service Announcement Lesson Plan (Scholastic)

YouTube: Changing the World with Video PSAs (lesson plan)

Create a Public Service Announcement (Common Sense Media)

Frank W Baker has been writing about media literacy here at MiddleWeb since 2012. He regularly leads workshops for teachers and students. (Learn more.) His most recent book, published by Routledge/Eye On Education is “Close Reading The Media” and includes ideas for lessons and projects throughout the school year. Frank curates the popular Media Literacy Clearinghouse website and shares daily tips and media literacy lesson ideas on Twitter @fbaker.