When Things Fall Apart, Revisit Your GRR Tools

A MiddleWeb Blog

Gradual Release of Responsibility is a key classroom strategy. In a year-long series two literacy coaches, Sunday Cummins and Julie Webb, explore ways to make GRR part of everyday practice.

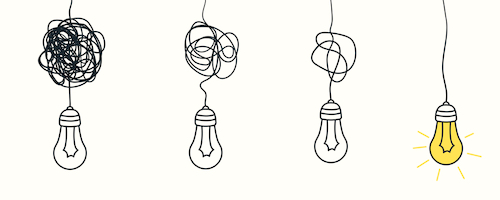

Even though we feel like we did a beautiful job modeling a type of strategic thinking like identifying a main idea, our students struggle unproductively during guided or independent practice.

We find ourselves still doing a lot of the work, asking questions, endlessly prompting, tugging mightily as we lead students to the main idea or whatever type of thinking we modeled. What to do?

In our last post, we discussed hosting a space for guided practice that nurtures productive struggle. Our suggestions included choosing texts or text excerpts that are “just right” for students, anticipating where some students might struggle during guided practice, conferring at those points, and thinking aloud for students during reading conferences.

If you find that guided practice continues to fall apart or that there is limited transfer during independent practice, you may need to examine and adjust how you implement particular phases of GRR.

Nurture the ‘student as connector’ part of I DO.

Examine the role you are asking students to take while you model for them (I DO). Are the students engaged in a conversation with you and their peers about what you are doing to strategically process text? You might try some of the following:

● Ask questions like “What did you notice me doing?” and “How do you think this type of strategic processing helped me understand the text better?” and “What did you see me do that you need to do on your own?”

● Nudge them to elaborate by prompting with “Say more about that.”

● Provide an anchor chart that small groups of students can reference as they discuss what they saw you doing.

Giving language to the processing they see you do helps students make stronger connections to what they need to do on their own.

Make sure guided practice is focused mostly on what was modeled.

If you have modeled identifying a main idea or some other type of strategic processing, then that is just what students should have an opportunity to do multiple times during guided practice. (Guided practice may take place over several lessons.)

It’s tempting to ask students to do more. To also find the supporting details. To also summarize their learning. But some students may just need to focus on finding the main idea in multiple sections of an article or text, or in multiple short sources. Within these conversations, though, there are lots of natural opportunities to talk about the content of the text and to do some other types of strategic thinking.

As we synthesize information to identify a main idea, we notice key details or what seems to be important. This is how we get to the main idea. Without getting into a big focus on “supporting details” or “summarizing” (which increases the cognitive load), we can have conversations about main ideas that deepen students’ understanding of the content of the text. We can ask questions like the following:

● What did you learn in the text that makes you think so?

● How did helping you think about the main idea help you retain the information in this source?

● So why is this main idea important to think about?

If a student doesn’t demonstrate a need for additional practice on what you modeled, then by all means address the need they do have, even if it’s something you didn’t anticipate. Every conference should include thinking about what was learned, though, and, as a result, may lead back to discussing what was focused on during the modeling (e.g., the power of main ideas to help us anchor our thinking).

Offer additional scaffolds or a new approach.

Early in learning a type of strategic processing like identifying a main idea or identifying a text’s structure as a way to retain information, students may need extra scaffolds. For example, during guided practice for finding the main idea, we might provide a list of “thematic” vocabulary that students can reference. We might give students a list of possible main idea statements to draw from as they make sense of a text.

Sometimes we might need to change the strategy we are presenting. With a 5th grade group of students working on identifying main ideas, Julie modeled identifying a main idea by thinking about what a text was mostly about and what was important about that. The next step was to return to the text to identify key details. Things fell apart when the students tried to identify main ideas this way.

This strategy didn’t seem to be concrete enough for them so Julie shifted to a different strategy. She modeled and guided the students in identifying details that seemed important. She worked with students to combine related ideas and eliminate those that were interesting but that they deemed less important.

Through this process and the ensuing discussion, students began to see how the details they had gathered could be assessed to reveal a main idea. From this initial success, and with many additional sessions of modeling and guided practice, her students began to identify main ideas more easily.

Stick with one type of strategic processing awhile and revisit.

Much of what we plan for during instruction is driven by curriculum and standards, but our students will not do the learning they need to do if they don’t have time to learn. The use of GRR for teaching a particular way of strategic processing may take many lessons to implement.

This built-in time gives students a chance to evolve in their roles as Connectors, Apprentices and Catalysts and eventually as Navigators operating largely on their own (while reading across the content areas).

This doesn’t mean you can’t focus on other types of strategic processing students reveal they need to learn or use. It just means we can’t abandon or bounce from one strategy to another. We need to keep an eye on what we have taught, whether we’ve provided time for learning to occur, and whether we might need to revisit a particular type of strategic processing.

Recognize when you might need to start again.

We’ve got to be nimble when balancing the competing needs of students and also flexible in our approach, especially if it looks like things are falling apart.

When things do go sideways, it’s an opportunity to reflect on whether we are in the appropriate phase of GRR, on how we are demonstrating or asking students to practice, and on the evidence that students put before us. Reflection in each of these areas can help us pick up the pieces and start again with a fresh approach and perspective.