Girls and Dreams and STEM

A MiddleWeb Blog

Bill Ivey is a teacher and middle school dean at Stoneleigh-Burnham, an all-girls independent school in Greenfield, Massachusetts, where STEM education is becoming a priority.

Bill Ivey is a teacher and middle school dean at Stoneleigh-Burnham, an all-girls independent school in Greenfield, Massachusetts, where STEM education is becoming a priority.

In an August post at his school’s View from the Nest blog, Bill noted that “girls schools have strong track records increasing the self-confidence of their alumnae in a number of ways – for one, a graduate of a girls school is three times more likely to enter the field of engineering. The potential for this initiative is enormous.”

Bill, who has a long association with MiddleWeb dating back to his leadership in our online community during the early 2000s, is a wise and passionate advocate for gender equity and the opportunity for all girls to learn everything and do everything they want to do. We’ve invited him to guest post here at STEM Imagineering, with SI lead blogger Anne Jolly offering comments. – John Norton, MiddleWeb co-editor

Not long ago, I stayed overnight with my brother and his family so I wouldn’t have to get quite so early a start to attend a Boston conference at Simmons College. The conference, entitled “Dreaming Big: What’s Gender Got to Do With It?”, would present a study on middle schoolers and career aspirations and provide opportunities to discuss implications and ideas for follow-up.

My brother and sister-in-law enjoy the TV program “Modern Family” (as do I), and after we caught up on our lives for a bit, we settled in to watch the evening’s episode. In retrospect, it turned out to be a good warm-up for the conference to come. The show, progressive as it is in some ways, does in other ways reflect the kind of stereotyping about work that is too often seen in the media. One example: neither of the two moms in the show have a salaried job.

Luckily for middle school girls, the media is only the third strongest influence on their career aspirations. As you might expect, schools and parents are the two most dominant influences. And as you might also expect, single-gender environments (like Stoneleigh-Burnham, where I’ve worked for the past 12 years) can have a positive effect.

The study being presented used Girls Scouts of Eastern Massachusetts as a proxy for girl-centered organizations, and looked at the views, opinions, and attitudes of 1200 middle schoolers, including 487 Girl Scouts, 299 girls who were not in the organization, and 414 boys. (Here’s a press release about the study.)

What girls say about STEM and careers

The study (here is a summary) painted a picture of middle school girls who, in envisioning their lives as adults, are confident and ambitious, want to enjoy what they do, desire financial security, and value time with family friends. It also showed that girls are more likely than boys to stop work and care for children. They are also more relationship focused and more wiling to consider jobs historically dominated by women. Such jobs (for example, teaching) continue to be less attractive generally.

Along with these more general findings, the study also showed a measurable, positive effect from girl-centered organizations. They can help girls resist the pressures of the culture in which they live and remain true to themselves and what they want out of life. As one of my 8th grade advisees said the other day, “I know what I learned last year. I learned to speak up and to speak with conviction.”

The push-back culture

Of course, as long as our culture continues to push back against confident, ambitious girls, our work will not be done. For one thing, those girls who do not have the benefit of the support of girls schools and girl-centered organizations will continue to eclipse themselves to a greater degree than their more fortunate sisters.

But even girls who have that additional support have to deal with the notion that significant parts of society may not want them to be all that they can be, and that fact does continue to shape their lives. And realistically, society also puts boys in little boxes that do not necessarily fit them. So really, as we teach girls – and indeed all children – to empower themselves in the face of resistance, we also need to work together to eliminate that resistance.

“Not in my lifetime”

During a morning session at the conference, noted author and speaker Rachel Simmons was asked, essentially, if she could envision a future where true gender equity will have been achieved. “Not in my lifetime,” she responded.

Her words hung in the air. And maybe she is right. But if during our lifetimes we have not, to paraphrase arts activist Peter Sellars, closed the gap between dream and reality, we will not have done our job. Encouraging STEM studies in the adolescent years, for girls as well as boys, is one important place we can begin to do more. But how?

Some things we can do

Most important, as research currently suggests, is providing the example of a positive attitude towards math and science, especially among women, and extra-especially as the mother of a daughter. By avoiding phrases like “Math is hard” and “I can’t do physical science stuff” and focusing instead on “Let’s figure out how to do this,” girls can come to internalize a growth-oriented model toward STEM in particular and learning in general.

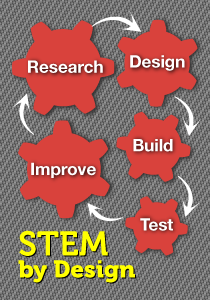

By learning this way, girls are more likely to come to believe in the value of hard work and how that can pay off, and are less inclined to think that they are born good or bad (more likely bad, being a girl) at math and science. Hands-on projects can further help, and discovery learning.

What ideas do you have about increasing the interest of adolescent girls in STEM subjects?

Powerful post, Bill! The creativity and problem-solving abilities of girls can be so unwittingly tamped down by their education circumstances that STEM careers can be on their back burners by the time they graduate.

I was an active supporter in the 60s of gender equality. We aren’t there yet, and I wonder more and more about one of your suggested strategies – teaching girls and boys separately. I know there are pros and cons on both sides, and I always taught mixed gender classes except in one instance. (I had a class of all boys who were non-achievers. It was an amazing adventure and, as my fellow teachers put it, at least these guys were going to have one positive, successful school year experience to remember.)

So I see real advantages to teaching girls and boys separately, especially in elementary and middle school. What do you think about high school?

Thank you so much for raising these questions. You are a true champion of good, solid learning practice, and I claim you as one of my favorite virtual colleagues!

Thanks, Anne! I appreciate your support, especially as you happen to be one of my favourite virtual colleagues as well!

As I think about it, I find that I believe that if you are going to have all-girls classes during any part of the K-12 years, middle school would be the highest priority. As girls begin to think about what it means to be a woman, they all too often begin to conform to what society expects of them. Girls schools can help them avoid the self-effacement and turning-inside I saw far too often during the three years I taught in a coed middle school, and not only remain true to themselves but also develop their best self even further. (…)

(…) That said, I do think all-girls classes in high school can also have a positive effect, and there is research, notably a 2009 UCLA study*, that confirms this. Alumnae of all-girls high schools, who of course may or may not have attended an all-girls middle school, are more likely among other things to go into STEM, to derive their self-esteem internally rather than externally, and to raise and use their voices, especially in activism.

* http://newsroom.ucla.edu/portal/ucla/graduates-of-all-girls-schools-85038.aspxv

I think, if you are going to have an all-girls school or class, the key is all in how you do it. Most of the research I’ve seen that does not support girls education points to practices that reinforce rather than defy stereotypes (e.g. painting walls pink and doing math problems about make-up). At my school, we do defy stereotypes. It can make all the difference.