How We Can Address Inequities Students Face

A MiddleWeb Blog

Let’s do a little exercise! Close your eyes. Think of one or more of your past students who struggled with education. Perhaps they didn’t come to class prepared. Or maybe they forgot something in their locker.

Let’s do a little exercise! Close your eyes. Think of one or more of your past students who struggled with education. Perhaps they didn’t come to class prepared. Or maybe they forgot something in their locker.

Or, perhaps, you couldn’t understand the language they were speaking, although you were sure it was some form of English, and so you corrected them, maybe in front of the whole class, maybe privately, requiring that they use “proper” English instead of the vernacular of their culture.

As you hold the picture of this student or students in your mind, I now want you to tell me what they looked like. Were they White, well-to-do students from middle and upper class families? Or were they Brown or Black or poor White students?

I am fairly confident that the majority of you that participated in this little exercise pictured a Brown, Black, or poor White student when you closed your eyes.

Unfortunately, in today’s political climate and our widespread racial and socioeconomic inequalities, the attempt to fix those inequalities – especially as they are manifested in education – has become a hot button topic that can evoke fear and anger. Yet most educators understand that there are disparities among our students in terms of access to resources, outside-of-school help, and time to do homework.

If you have been teaching for a while, I am sure that we could sit and swap stories about our past students who struggled in school because they had to work to support the family, or they had to watch younger siblings so parents could work to support the family, or any of the other myriad obstacles that can be placed in front of our students. And most of us could talk about what we tried to do to help, and what we now realize we got horribly wrong.

Yet we all want to do better, for as Maya Angelou once said, “When you know better, you do better.” So we read, we watch TED Talks, and we try to have open and honest conversations with our colleagues, but still our students of color and our low socioeconomic students continue to do poorly when compared to their middle and upper class peers.

Teaching for racial equity

Enter Tonya B. Perry, Steven Zemelman, and Katy Smith’s book, Teaching for Racial Equity: Becoming Interrupters (Stenhouse, 2022).

Perry, Zemelman, and Smith have created a guide for teachers wishing to become better at including and accepting the differences among their students of color and their White students.

Their book not only sets out a guide that educators can use in the classroom to have productive talks about race and race relations within the social construct of American culture. The authors also offer a glimpse into the struggle they each had as they attempted to write a book that gives voice to the frustrations and struggles of students (and teachers) of color.

Getting started

To start, the Introduction not only sets up how the contents of the book are laid out for the readers, it also gives definitions of racism and antiracism, it recognizes the difficulty and challenges educators may encounter as they work towards a more inclusive classroom environment, and it gives very concrete examples of how racism has affected education in the United States.

It encourages us to not only recognize the challenges that we will face, but to also “celebrate the success and creativity in our communities.” It is in the relationships that we build through our hard conversations about race and racial equity that will bring about real change, one conversation at a time.

Working for equity through the Racial Literacy Development Framework

Prior to the start of each chapter, the reader gets an intimate look into the challenges and triumphs of the writers as they worked together (one Black writer and two White writers) to make sure that what was delivered to educators was both informative and actionable.

Each chapter then examines a different aspect of Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz’s Racial Literacy Development Framework, a structure grounded in “critical love” so as to create a caring environment in which to work.

Also included in each chapter are open, honest, and critical writings from guest teacher-writers as they work to make their classrooms more equitable. They discuss going through the process suggested in the authors’ book, how it has affected them as teachers, and what hard truths they had to face as they reflected on some of their own preconceived notions.

And the beautiful thing about these reflections is that they are equal opportunity reflections – they come from White, Brown, and Black educators from both the South and the North as they work to confront the systemic racism they have witnessed, participated in, or experienced in their own lives.

“…through the process, we can examine and seek to understand our own development and the ways that race, experience, and aspects of privilege or lack thereof have impacted us. These tasks are reformative and not aimed to promote either guilt or self-congratulation.” (Introduction, p. 5)

The restorative nature of the RLD framework is felt throughout the book. While some of the conversations and discussion can make us feel uncomfortable, they are real and relevant and needed in order for us to correct and interrupt “racism and inequality at personal and systematic levels.”

Essential work for equity

My mom used to say that if you ever wanted to lose friends, talk about politics, religion, or money. There are few things that will break down communication faster. I would add race to that list. However, to be better educators, we have to have the hard conversations about race and how it affects education; we have to consider all variables and obstacles that can hinder equal education for all.

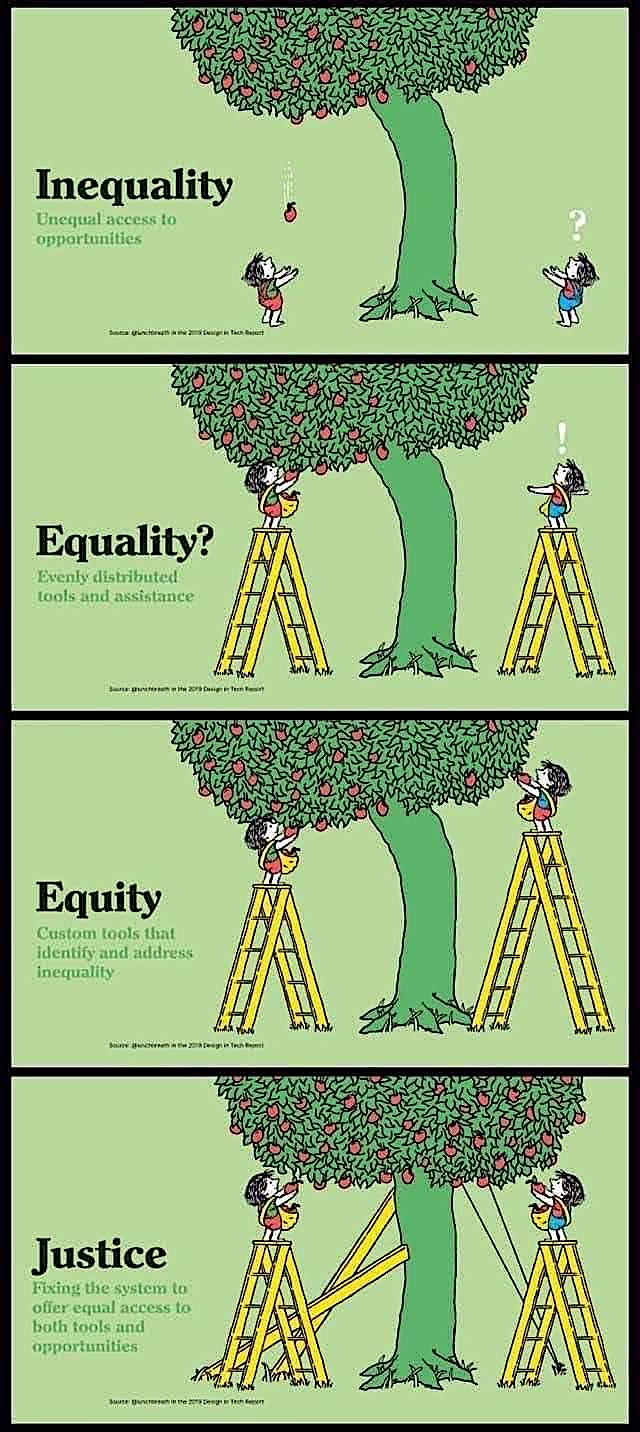

I often reference this graphic as I think about these issues and the important communication that needs to take place in and out of schools. It’s a good tool for deeper thinking and dialogue.

As much as many of us may want to steer clear of racial and racial inequality conversations, they need to be had. Because “real change in broader equity practices will occur as these interactions multiply and grow to impact even more lives to ultimately interrupt systemic inequitable practices.”