3 Top Take-Aways from Our Exploration of GRR

A MiddleWeb Blog

We want students to take more ownership of learning, but how do we help them make that shift, day to day, in real classrooms? In a year-long blog, Letting Go Is Messy, literacy coaches Sunday Cummins and Julie Webb have explored just that question. (See our links to each post at the end of this final article.)

By Sunday Cummins and Julie Webb

When we implement GRR, we are messaging to our students that there’s always room for improvement or growth, and that growing entails deliberate practice.

But this philosophy is also relevant to our practice as teachers. In her book Grit, Angela Duckworth describes kaizen as “resisting the plateau of arrested development” (p. 118). Whether you are new to implementing GRR or you have been utilizing this approach for years, it’s easy to hit plateaus. When our practice plateaus, we become less effective and that means less learning happens.

As educators in the field, Sunday and Julie have spent the last year exploring how to avoid this, asking ourselves, “How can we make our use of GRR stronger?” We’ve shared many of our discoveries with you here at the Letting Go Is Messy blog. What follows are our three top take-aways.

1. GRR is an active partnership

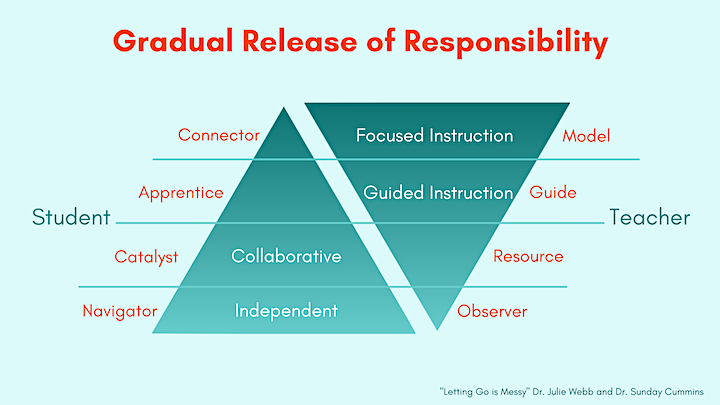

The phrases I do, we do, you do together, and you do that are commonly associated with GRR can be misleading. They place the teacher in control of the journey. There’s a sense of “I’m going to release responsibility to the student” which positions the student as passive until they receive the responsibility from the teacher and then the teacher as passive once she releases responsibility.

Really, though, the student and teacher should be active in all phases of GRR.

For example, during the traditional I do phase, while the teacher is modeling, the students need to be actively connecting to what the teacher is doing, asking “What do I already know about this type of strategic processing? What is the teacher doing that is unfamiliar that I need to pay attention to? How will I remember how to do this?”

During the you do phase, while the student is engaged in making sense of a complex source, the teacher needs to observe for learning and to determine which teaching objectives need to be included in follow-up lessons. By being cognizant of which phase the teacher and student are in and how their roles shift, we nurture a sense of agency and identity in our students, increasing engagement and maximizing learning opportunities.

2. GRR requires keen observation

A critical skill for teachers in every phase of GRR is the ability to notice what’s happening in the classroom and to respond accordingly. To be a noticing teacher means we need to develop thoughtful lessons with clear learning goals so that we know what to look for during teaching. A teacher might think:

My students need to practice using text features when they read to improve their comprehension of informational text. Today we’ll specifically explore how captions provide complementary information to the body of the text. During conferences, I’m going to watch for moments when students look over the images in the text and read the captions. I’ll ask a few questions to check for comprehension of how the caption supports the text, and if needed, I’ll think aloud to model how this is done.

Being a noticing teacher also means watching for the surprises that inevitably unfold when working with students. The same teacher might pause and reflect:

I didn’t realize that some of my students are relying too heavily on text features. I saw them scanning the text but not taking the time to read it carefully. Their answers during our discussion demonstrated minimal understanding. I need to move back into the modeling phase for those students to demonstrate how to balance reading both the body of the text and text features. I will plan to think aloud about how and why I need to integrate the two.

It’s a bit paradoxical, and often a bit messy, to create intentional plans knowing that you may need to pivot away from those plans. But ‘noticing’ teachers are adept at this dance, and they make it part of their practice to consider in advance how and why they might shift into a different phase of GRR.

3. GRR is flexible, not formulaic

If you search online for images that depict GRR you’ll be hard pressed to find one that truly illustrates the messy nature of how it plays out in real classrooms. Our own graphic representations of GRR don’t do it justice (though our attempts to encapsulate it have taught us a lot!). If you’re not careful, you may start to believe that GRR is a step-by-step recipe in which the teacher moves in one direction on a straight line from modeling down to independent practice.

Ah, how deceptively simple those graphics – even ours – can be! But experienced teachers (and our student readers) know that GRR is not a plug-and-play formula. It’s not even linear. Instead it’s a continual process of stepping forward and pulling back based on our observations, with ever-changing starting and stopping points. We are continually asking questions like:

● What do I know about my students?

● How can I use this information to decide whether to start with I do or to maybe start with you do to learn more about what they can take on?

● Which scaffolds do I need to offer in the next lesson (or in this moment)?

● Which scaffolds do I need to remove?

GRR demands that teachers be flexible and stay nimble as students show us what they know and can do.

A conclusion, but not “The End”

Our exploration of GRR has fueled even more excitement for us about the many ways this approach can improve teaching and learning. And while GRR is indeed a partnership, and relies on observation and flexibility, there’s another message we want to leave you with in this post.

GRR demands that the topics and texts we put in front of students are worthy of our students’ time and energy. There are so many learning demands in today’s classrooms and even more topics and texts competing for our attention outside the classroom. The truth is we can’t possibly teach everything that’s worth knowing.

What we can do, though, is teach our students how to make sense of texts for themselves. As messy as it might be, we can’t think of a better way to prepare them than by employing the gradual release of responsibility. And we think there’s more to learn about this essential approach to teaching and learning so this blog series isn’t the end of our journey. We still have more exploring to do!

The Complete Letting Go Is Messy Series:

The Messy Business of Gradual Release (GRR)

7/21/21

Teachers Are Active in Every Phase of GRR

7/28/21

A GRR Teaching Move: Begin with “You Do”

9/27/21

GRR: Who’s in Charge? Teacher or Student?

10/24/21

Help Readers Learn ‘Strategic Processing’

11/30/21

Making the Most of GRR’s Guided Practice

1/26/22

When Things Fall Apart, Revisit Your GRR Tools

2/28/22

GRR: When the “You Do Together” Feels Shallow

3/30/22

GRR: When It’s Time for You Do, Help Them Fly!

5/8/22

The 3 Top Take-Aways from Our Exploration of GRR

6/19/22