Bringing Schoolwide Equity to Multilinguals

A MiddleWeb Blog

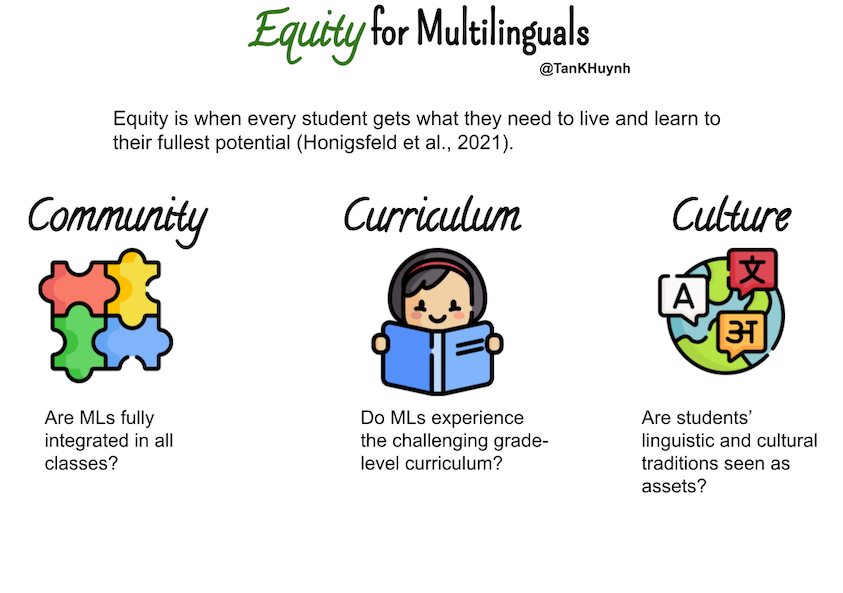

Fortunately, there are more and more people joining this march. I offer a framework called the 3 C’s of Equity to guide schools on this journey to provide an equitable learning experience for their multilingual learners.

Community

The first C is the easiest to spot and the easiest to implement. We need to ask if multilingual learners are fully participating in every aspect of the school. At the class level, are multilingual learners warehoused in a resource room with a language specialist for the majority of the day? If so, this is segregated learning, and segregation cannot be equal.

There are students with developing proficiencies that spend a period, several periods, or the entire day not in classes with their same-grade level peers, learning from the homeroom or content teacher. How can this policy-supported segregation be equitable?

I know the intention behind pull-out service is to fast-track English language acquisition, but this comes at the great cost of students’ less-than-full integration in a school. Pull-out is an antiquated, deficit-based model where students’ language skills privilege them with participation in the community (Nora & Echevarría, 2016).

Multilinguals can feel like second-class citizens as they are not fully integrated into the school. They may even be treated differently by their same-grade peers because the segregation creates an “othering” of students (Honigsfeld et al., 2021).

Lastly, segregating multilinguals also communicates to teachers that some multilinguals do not deserve to be in their class until the achieve a certain level of proficiency. Hanging onto this myth of proficiency, some teachers can exempt themselves from accepting responsibility for multilingual students altogether by deflecting it to the language specialists.

If language proficiency is a barrier to enrolling in mainstream classes, we run the very real risk of excluding multilinguals for years until they achieve “native English” proficiency (Seals, 2021).

A more inclusive, assets-based model is one where students fully engage in a community, and this community engagement provides the fuel for their academic and linguistic development (Kunc & Van der Klift, 2018). Let’s create policies where students are fully integrated by default and not by proficiency.

Now stop to reflect on your context:

● Are multilingual students enrolled in sheltered content classes taught only by language specialists?

Imagine a school experience for a student who is withdrawn from art so he can go to extra English classes even though art forms a significant part of his identity. Will he think that English is more important than art and that he is only valued when he achieves an advanced level of English proficiency? Every service model has its limitations, and this contraction of exposure and identity is the cost of pull-out programs.

Ask: When we say yes to extra English classes or segregated content classes, what do we say no to? If we believe that students should enroll in art, music and similar classes for their many academic and emotional benefits, why would we rob multilinguals of the same opportunities?

The pull-out model exacerbates the achievement gap because it bars enrolling in specials and content classes, which offer authentic experiences to learn content and develop language skills (Minaya-Rowe, n.d.).

I am not opposed to a dedicated English language development class as there are benefits (Saunders et al., 2016), but this class cannot come at the high cost of not being enrolled in other special or content classes.

Curriculum

Even if multilinguals are fully integrated into a school, this does not automatically make it equitable. Here’s a story I offer as an example:

Jai Dee is a highly literate Laos student, but she is a beginner in English. She enrolls in the 7th grade and attends all her peers’ classes plus a language acquisition English class. However, during science class, while her classmates are learning about ecosystems, she is required to learn from basal readers with some content only loosely connected to the science lesson.

This is not equitable because she is not learning the same content and not held to the same standards as her peers. It’s as if she is in a class within a class since she is not expected to engage in the same assessments or learn the same standards.

In this scenario, when will Jai Dee ever catch up to her peers? When will the opportunity gap ever close? Does she look around the room and feel embarrassed when she realizes that she is not engaging in the same activities as her classmates? She sure does!

The longest empirically-based framework for mainstreaming multilinguals suggests that multilingual students can successfully learn grade-level content and language simultaneously (Echevarría et al., 2017). In this model, all teachers become teachers of language and literacy, especially discipline-specific language and literacy.

How is this possible? Homeroom and content teachers are not alone on this journey! They can collaborate with language specialists to co-teach. Each plays an essential role based on their expertise. The content teacher provides the topic-specific knowledge and skills required while the language specialist teaches the language skills needed to be successful (Honigsfeld & Dove, 2019).

Culture

When multilingual students have full access to the school community and the curriculum, we still need one more component for equity: culture. Does your school sustain and maintain students’ connection to their languages and cultures year-round, not just honor and celebrate on festive occasions? Indicators of inequitable cultural practices include:

● racist “English only” signs plastered around the campus

● demanding English usage even among same-language peers

● curriculum that reflects one dominant culture, usually not the ML students’ cultures

Will Jai Dee go through the 7th grade learning only about the Age of European Exploration, the Italian Renaissance, the American Revolutionary War, and the Industrialization in Great Britain? Haven’t we seen this educational and linguistic imperialism before when colonizers outlawed and punished their conquered people for using their indigenous languages and prohibiting them from maintaining their rich cultural practices?

Encouraging multilingual learners to use their home languages and to maintain their ways of being not only boosts academic achievement, it affirms their identities (Paris & Alim, 2017; Cummins, 2014).

Conclusion

If multilinguals are to reach their full potential, we must examine school-imposed limitations. We must first be brave enough to turn our backs against practices that demonize certain languages and pay lip service to cultural diversity.

We must walk alongside our students and their families on a journey that welcomes all in whatever way they show up because equity is not a word found in a mission statement – it is the rhythm pulsating in a school’s heart.

References

Cummins, J. (2014). Reversing Underachievement among Immigration-Background Students: what does the research say? Politeknik. http://politeknik.de/reversing-underachievement-among-immigrant-background-students-what-does-the-research-say-jim-cummins-the-university-of-toronto-2/

Echevarría, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. (2017). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP Model. Pearson.

Honigsfeld, A., Dove, M. G., Cohan, A. F., & Goldman, C. M. (2021). From equity insights to action: Critical strategies for teaching multilingual learners. Corwin.

Honigsfeld, A., & Dove, M. G. (2019). Collaborating for English learners: A foundational guide to integrated practices. Corwin.

Kunc, N., & Van der Klift, E. (2018). EARCOS Teachers Conference. EARCOS Teachers Conference. Bangkok.

Minaya-Rowe, L. (n.d.). Options for English Language Learners. AASA | American Association of School Administrators: The School Superintendents Association. https://www.aasa.org/schooladministratorarticle.aspx?id=4140

Nora, J., & Echevarría, J. (2016). No more low expectations for English learners. Heinemann.

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Saunders, W. M., Foorman, B. R., & Carlson, C. D. (2006). Is a Separate Block of Time for Oral English Language Development in Programs for English Learners Needed? The Elementary School Journal, 107(2), 181-198. https://doi.org/10.1086/510654