6 Ways to Help Students Master Media Fluency

Three leaders in the digital citizenship movement offer strategies educators can use to teach media literacy in highly effective ways.

By Shawn McCusker, Richard Irvan & Tom Driscoll

Most of us who follow politics across the globe are aware that the Age of Information, which began with the birth of the Internet, has given way to what we might call the “Age of Disinformation.”

Now we have incredible amounts of useful information at our fingertips, as well as older outdated information, and (increasingly) false information created specifically to deceive or manipulate people’s thinking.

In fact, the rapid proliferation of fake, misleading and biased information has become a serious worldwide challenge facing each and every democratic society. If informed voters are the foundation of a democratic society, misinformed voters will be the ruin of it.

It is important to understand that not all “fake news” is alike. Misinformation is “false information that is spread, regardless of whether there is intent to mislead” (Dictionary.com).

For instance, a family member might unwittingly share misinformation via a Facebook news story without knowing that it is out of date. In contrast, disinformation contains deliberately misleading or biased information, where the creator knows full well how they are manipulating facts and what their purpose is in doing so.

Media literacy helps equip students with the skills and habits to navigate today’s tricky online landscape. And while it is common to hear experts call for media literacy, you are less likely to hear people share what exactly media literacy should look like.

Here are six specific strategies and resources that you can use to develop media literacy with your students.

Lateral Reading

Lateral reading is a powerful strategy and habit to cultivate for evaluating online information. This involves opening new tabs to fact-check a site or message while you are reading it, to see what other online sources say about it. This approach differs from traditional, “vertical reading,” where you simply read an article on its own, top to bottom.

Students can often be tempted to trust a well-designed, professional-looking website when viewed by itself. Lateral reading provides the opportunity to confirm or dispute a source’s reliability by assessing it in the broader information landscape.

For instance, students are prompted to look up information about an author (like the person behind a tweet) to determine their trustworthiness on the posted topic. They also might dig into the sources cited at the bottom of a Wikipedia page, to assess the underlying biases and reliability of research (“How to Use Wikipedia Wisely”).

In this way, lateral reading builds upon strategies teachers may be familiar with, like the CRAAP method, where students consider characteristics of a source (e.g., currency, relevancy, authority, accuracy, and purpose).

(Source: Stanford COR via PVCC Jessup Library)

Lateral reading offers further benefit by familiarizing students with resources they can consult when reading, including fact-checking organizations’ websites. Civic Online Reading at Stanford offers a sequence of high-quality lessons for teachers to model and guide students to improve their skills in lateral reading.

Understanding and Identifying Bias

Teaching students to identify bias is a challenge, but there are many tools that teachers can employ to help kids practice the skill. More importantly, these tools allow students to engage in the process actively.

The News Literacy Project’s free “Checkology” is one such tool. Their “Understanding Bias” module lets students dive into five different categories of media bias to understand the complexity of bias and how their own beliefs can influence their perception of media.

News Literacy Project also offers The Sift, an educator newsletter that highlights trends in the media and provides links to resources and activities.

Exposing the Motives of Misinformation

Common Sense Media has unique educator resources for exposing the motives of misinformation. What sets their resources apart is how they seek to incorporate students’ personal experiences to engage them in the process without becoming cynical.

Their view is that fairness actively avoids “creating or implying a hierarchy of credible news sources.” Therefore, they advise that students use their preferred media platforms but they do so in a more effective and critical way.

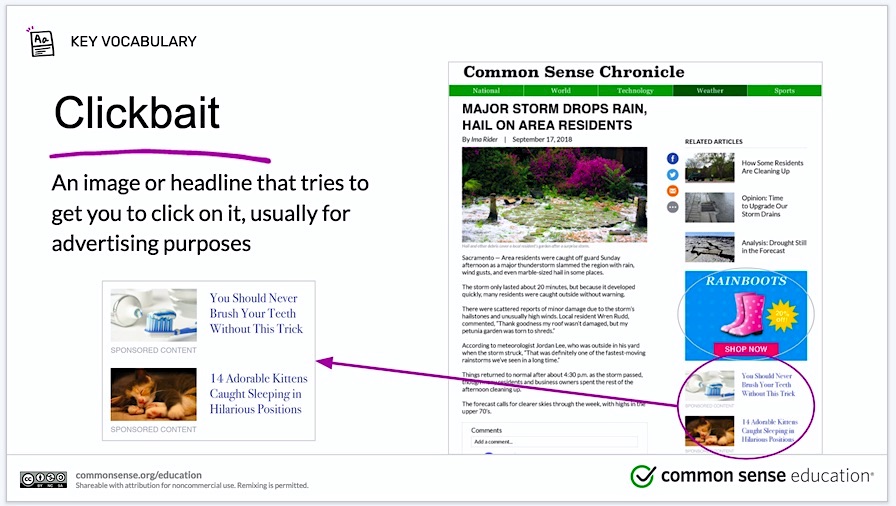

Common Sense has lessons for students of all ages. Their lesson called “Clicks for Cash” explores the concept of “clickbait” and how fake news can become profitable and drive the creation of even more fake news. The lesson concludes with a Take a Stand activity in which students brainstorm ways to combat the spreading of fake news. (This free lesson is designated Grade 11 but easily adapted for middle school. Slides, teacher version, etc. included.)

Analyzing Historical Sources

Media literacy can and should be integrated into coursework across subject areas, but one place it fits particularly well is the history classroom.

Historical thinking skills are a priority across state frameworks, and there is a natural overlap with media literacy in the focus on critical analysis of documents. The Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) is a nationally recognized source for free high-quality instructional materials in this area, particularly their Reading Like a Historian lesson plans for middle and high school.

Their engaging activities titled Lunchroom Fight (1 & 2), for example, guide students to consider not only multiple perspectives on an event, but also how to evaluate evidence in conflicting accounts by considering corroboration and sourcing. This can provide students with a solid foundation in critical nonfiction reading that can be extended throughout the curriculum.

Navigating Digital Information

A powerful resource for navigating digital information comes from a collaboration between author John Green (of YouTube’s “Crash Course”), MediaWise, the Poynter Institute and the Stanford History Education Group.

This 10 part YouTube series explains, for example, how algorithms are used by marketers to provide users with information that they will find interesting or entertaining rather than information that is most factual or accurate. Other episodes discuss evaluating photos and videos and evaluating data and infographics.

Together this series provides students with a deeper understanding of how information arrives in our feeds – and with the skills needed to make sense of it.

Understanding the Power of Images

Facing History and Ourselves is an organization that provides many free resources for digital literacy learning with images. As part of the unit Facing Ferguson: News Literacy in the Digital Age, the lesson titled The Power of Images has students explore the impact of imagery and how it can be interpreted differently based on people’s backgrounds, life experiences, and existing biases (Facing History and Ourselves, n.d.c).

Students examine how various news outlets portray the events through imagery, then engage in a simulation in which they play the role of editor who must determine which cover image should accompany the story. This experience then leads to a discussion around the role that imagery plays in reporting and consuming news media.

Students Need Media Literacy Fluency

As calls for media literacy continue, we need something more than a vague understanding of what it takes to build it. We should aspire for a higher standard, that of media fluency, where each student can not only identify the challenges of the Age of Disinformation but knows how to overcome them.

By investing the time and resources to establish quality media literacy education in our schools, we can ensure that students will navigate around those challenges carefully and intellectually to ultimately find the truth.

Also see this MiddleWeb article by McCusker & Driscoll:

5 Civic Education Steps to Preserve Democracy

Richard Irvan is Associate Director of Professional Learning at Digital Promise, currently supporting national initiatives to close the digital divide, and a former middle school history teacher and curriculum specialist.

Tom Driscoll (@tomdricolledu) is co-author of Becoming Active Citizens and the CEO of Edtechteacher. He is a former digital learning director for the Bristol Warren Regional School District in Rhode Island, where he led the district’s digital learning transformation. Tom began his career as a high school social studies teacher in two public school districts in Connecticut. He holds a master’s degree in computing in education from Teachers College, Columbia University.