What Changes Kids’ Minds about Poetry?

By Linda Rief

Growing up I never liked poetry. I shuddered each time I heard the word in school. Poetry meant finding the hidden meanings the poet had worked so meticulously to hide from his reader.

Growing up I never liked poetry. I shuddered each time I heard the word in school. Poetry meant finding the hidden meanings the poet had worked so meticulously to hide from his reader.

Every word was a symbol for something deep and mysterious, and our task was to unravel all the tricky nuances. I was not good at that. I rejected the entire notion of poetry with the same distaste I had for canned peas or raw oysters.

I left the reading and understanding of poetry to the intellectuals of the world. The smart kids. I was not clever enough to understand it. Poetry made me feel stupid, and that is not a good feeling. Best to simply avoid it.

Then, years later, I heard William Stafford share his poetry aloud at a reading at Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire.

I don’t remember a single poem—I just remember his voice, his words, hanging in the air, waiting for me to grab them, to make them mine.

I was astonished. The hour and a half slid away and I was left sitting in a row of empty chairs as other listeners left. What had just happened? That was poetry?

My students were not convinced

The next day I asked my eighth grade students if they had any favorite poets. Their reaction was my reaction forty years earlier. They cringed at the word poetry. Their faces actually changed – eyes widened, shoulders folded – and they pulled into themselves as if protecting their bodies from something horrible.

“No, no,” I said. “I heard a poet last night and it was wonderful. I could have listened to him for hours.”

They were not convinced. Furthermore, they convinced me why they hated it. Quizzes and tests. Count the syllables. Name the kind of poem it is. Identify the rhyme scheme. Define meter. Write a sonnet. Search for the symbolism. Memorize and present a Robert Frost poem. What’s the meaning of the last line, the first line, every line, in his poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”?

I was beginning to hate poetry again just listening to these eighth graders. “Please, please, we’re not going to do a poetry unit, are we? Say no!” they begged.

And I didn’t—do a poetry unit. And I haven’t—done a poetry unit.

But I wanted the students to experience poetry. To recognize and relish the language. To experience the feel of a moment. To notice and try the ways a poem is shaped. To see how “brevity and intentionality” (Clark, 2017) can carry so much feeling. To see poems stretching or curling into themselves. To enjoy it. To read it.

To understand any of this, they had to read it.

As teachers, we might have the wrong idea about what it means to “teach” poetry.… so many of us see poetry only as a means to teach figurative language and analytical skills to students, and as a means for students to read the poems that we love or that we were taught…

— Amy Clark 2017 (“No More Apologies,” Sometimes You Just Need a Poem blog)

Heart Books: Students select poems that tug

My book Whispering in the Wind (2022) is about the value of reading poetry, finding the poetry that allows us to get inside our feelings and notice what the poetry does to us and for us as readers and writers.

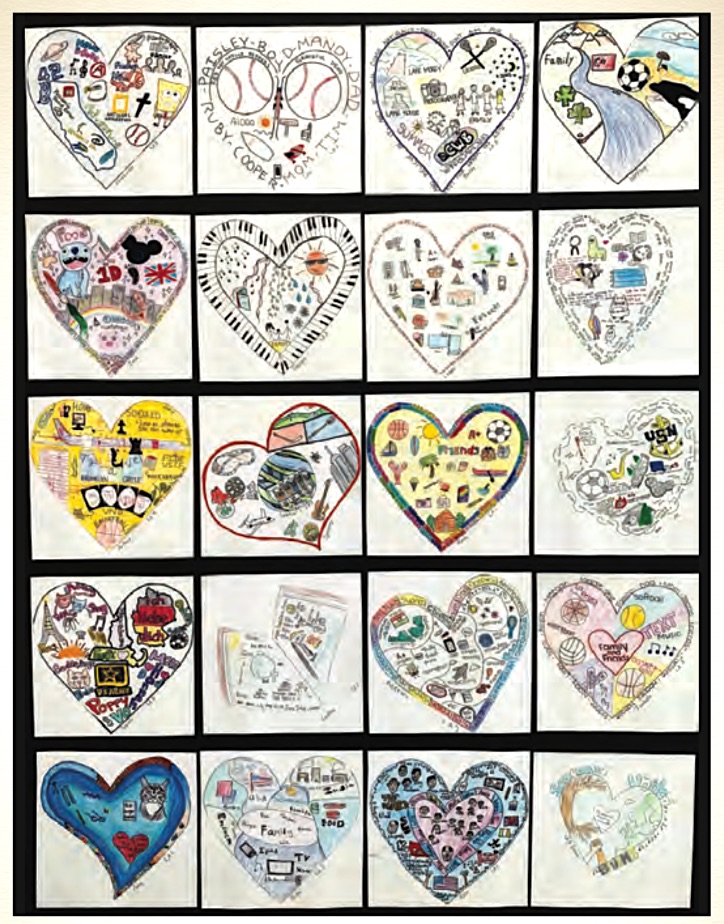

In looking for a way to encourage students into reading more poetry – or any poetry – I gave them each a blank book, had them use their Heart Maps (from Georgia Heard’s Awakening the Heart) as covers for the book, and asked them to fill the blank book (soon known as their Heart Book) with the poetry of their choice – the poetry that tugged at their heart and mind – in double-page spreads throughout the year.

I gave them an example of what I meant on my own first double-page spread. I copied the poem “The Writer” by Richard Wilbur, wrote down what I noticed about it and why it was an important poem to me, and illustrated the poem with some photos that extended the importance of the meaning for me.

Because I only had the students for 50 minutes a day, adding something else to an already packed curriculum seemed overwhelming. I asked the students to work on their Heart Books during transition times – a day or two before or after a holiday or vacation, the last day of the week before transitioning to another Book Club or genre of writing, or during time left after finishing a mandated state test.

Throughout the year I recommended poets, taught them several art techniques, and made poetry collections and art supplies readily accessible for their use during any and all transition times.

Their Heart Maps were the vehicles that lead my students to those poems that spoke to them closely (personally) and widely (beyond ourselves). In the same way the Heart Maps focused on those things, those beliefs, those issues that mattered most to the students, the poems they found gave them pause for thinking even more seriously about themselves and about others.

Filling our classrooms with many voices

What’s most important, as we make poetry available to our students, is that we make sure our classrooms are filled with the voices of poets like our students, yet also filled with the voices of those outside our students’ experiences, so they can see how the world might be different from their own lives. Students not only need a range of poets available to them, they need —

● Choice about which poems or poets they read

● Contemporary and classic poets from multicultural backgrounds

● Time to find, read, hear and respond to the poems that speak to them

● Time to reflect on their poems through talking, writing, and drawing about them.

We can guide them with open-ended questions about the poetry —

● What came to mind as you read this poem?

● What did the poem make you think or feel?

● What in the poem made you think or feel that way?

● What did you notice about the way the poem was written?

● What did the poet do that you might try in your own writing?

Quickwrites: Use mentor texts as doorways

Another way to introduce students to poets and the language of poetry on a daily basis, in a low-stakes way, is to use a poem or a powerful excerpt from a novel or essay as a mentor text for quickwrites (Rief, The Quickwrite Handbook, 2018).

Have the students write for 3-4 minutes: anything the writing brought to mind for them, or they borrow a line and let the line lead their thinking. In this way they hear language, see the shaping of the writing, and respond in a personal way that allows for deeper connections with the poem.

The simple use of these mentor texts does double-duty – you are recommending the poet and/or the novel/author every time you share these pieces. These short pieces of text jumpstart the students’ thinking and often lead to more extended writing and larger pieces of their own.

When choosing mentor pieces, I always choose those that lead them in the direction of the genre of writing we are studying: personal narrative or essay, fiction, or persuasive writing, for example. We often go back to these mentor texts to look at what the poet/author did to create the feeling (word choices, phrasing, line breaks, leads and endings, repetition) that we might try in our own writing. The purpose of anything we do is always to help each of us find and strengthen our own reading and writing.

Illustrated Lines: Using art with their own work

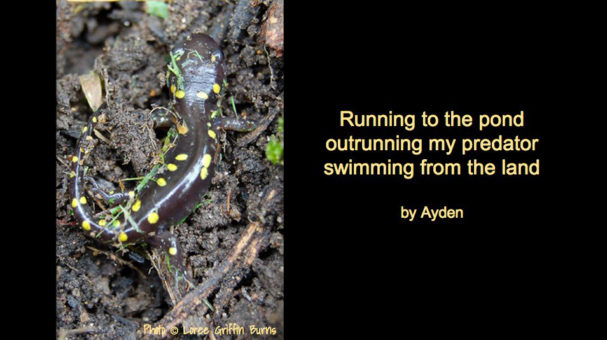

For the joy and pleasure of learning, teach your students about art invitations – contour drawing, watercolor, torn paper, zentangles, photography. (I share some of these in Whispering in the Wind.) In addition to using the art invitations in their Heart Books, I also invite them to use the art to illustrate a piece of their own writing. Instead of posting whole pieces of each student’s writing (including poetry), I ask them to pull out one phrase, one line, or one short paragraph or verse, which is either the most memorable to them or might be the most eye-catching to a reader.

The simple act of searching for an indelible line, and perhaps not finding one, leads students to really look at, and pay attention to, their word choices, their phrasing, their intentional shaping of the writing. It frequently leads to revision, often toward more poetic language that made the reader see and feel something.

From Loree’s Blog

Once they find those lines, I ask them to illustrate them with one of the art invitations. Post this art and short writing for other students to view and read. This grabs their attention and often leads to the reader asking the writer if she would let them read her whole piece. It builds confidence in the writer and helps both writer and reader notice what makes memorable writing.

We might even change their minds

Heart Books. Quickwrites. Illustrated lines. They lead the students to paying more attention to poetry and even changing their minds about it by seeking it, and trying it, on their own. My student Greg wrote:

I thought that poetry was the worst thing in the world. I hated it. Every time poetry came up in LA class I wanted to scream. In 4th grade we had to write poems about what the teacher wanted you to write. You didn’t see any examples. . . . And you had to share your poem no matter how bad it was. I hated it.

Before doing the Heart Books I thought that the only good thing about poetry was that poems were short. Now that we are done, I admit I enjoyed the poems, and though I won’t admit it out loud, I think that in high school I’d enjoy taking a course on poetry.

Read a MiddleWeb review of Linda’s latest book: Whispering in the Wind: A Guide to Deeper Reading and Writing Through Poetry.

References

Clark, Amy. 2017. “No More Apologies.” Sometimes You Just Need a Poem (blog), August 30. https://sometimesyoujustneedapoem.blog/2017/08/30/

Frost, Robert. 1975. You Come Too. New York: Henry Holt.

Heard, Georgia. 1999. Awakening the Heart: Exploring Poetry in Elementary and Middle School. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Rief, Linda. 2022. Whispering in the Wind: A Guide to Deeper Reading and Writing Through Poetry. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Rief, Linda. 2018. The Quickwrite Handbook: 100 Mentor Texts to Jumpstart Your Students’ Thinking and Writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Linda left the middle school classroom in June of 2019 after 40 years of teaching Language Arts with eighth graders. She misses their energy and their apathy, their curiosity and their complacency, their confidence and their insecurities. But mostly, she misses their passionate, powerful voices as writers and readers.

Linda is now an instructor in the University of New Hampshire’s Summer Literacy Institute and a national and international presenter on issues of adolescent literacy. For five years Linda co-edited, with Maureen Barbieri, Voices from the Middle, a journal for middle school teachers published by the National Council of Teachers of English. In 2021 she was honored with the Distinguished Service Award from NCTE and in 2020 received the Kent Williamson Exemplary Leader Award from the Conference on English Leadership, in recognition of outstanding leadership in the English Language Arts.