Compassionate Discipline and the Adolescent Brain

By Marilee Sprenger

As middle school teachers, we love the electricity in the classroom that comes from curious if hormonal minds. We have the opportunity to work with brains that are going through major changes, and we can help these students make choices that result in high functioning, caring adults who are forward thinking, kind and compassionate – with the ability to change the world in the best of ways.

Yes, there will be challenging behaviors. They are still learning to recognize and control their emotions. They are learning how to build relationships and make responsible decisions that will set their course in life.

In the middle grades our students’ brains are practicing those behaviors to see which ones work and which ones lead them into troubling situations. We must look at these challenging behaviors and respond to them constructively, compassionately, and consistently.

It Really Is about Compassion

Our role is not to control their behaviors but rather to respond to the behaviors in ways that help them grow. Our best approach is to use compassionate discipline. This discipline style cultivates autonomy and self-awareness.

Compassionate discipline is composed of acts of compassionate empathy. SEL pioneer CASEL (The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning) has conducted research on discipline strategies that promote social-emotional learning. Their findings show a reduction in problem behaviors, better graduation rates, increased motivation, higher grades and higher graduation rates.

As teachers build relationships with students, the basis for all learning, there are fewer discipline referrals. Students who have a relationship with their teacher feel like they belong in their classroom. “Belonging” rather than “fitting in” is what the brain craves. (Brown, 2018)

Building relationships can begin simply through greeting students individually at the classroom door. They can become more intimate as you share your story with them and show them your vulnerability, and can expand as you practice a simple 2 x 10 activity (Wlodkoski, 1983) in which you spend 2 minutes each day with a student talking about anything but schoolwork.

It is through relationships that you will be able to model empathy, a skill that can be taught as well. Teaching empathy can be done with strategies like having students do volunteer work at school or in the community. Experiencing the response they get from helping others at a nursing home gives them feelings of pride and offers them the opportunity to see life from the point of view of others.

Caring for a classroom pet or interacting with an emotional support dog can also elicit empathy from even the “toughest” students. “Smokey is cold! Shut the window!” or “Smokey looks hungry. What can we feed him?” are indicators that students feel empathy for the animals. Allowing themselves to take the perspective of others is cognitive empathy that can change their lives.

Helping Our Students Self-Regulate

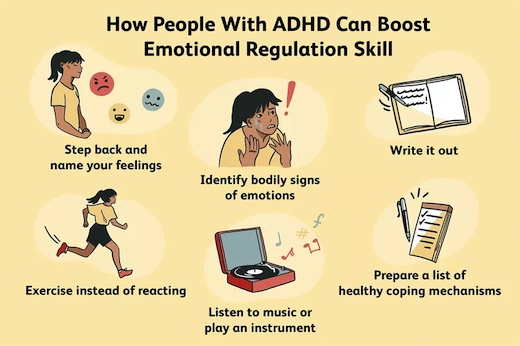

Situations in which discipline is required often arise because students cannot self-regulate. The ability to recognize one’s emotions and manage them are the first two SEL competencies defined by CASEL. The Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence uses the acronym RULER: recognize, understand, label, express, and regulate emotions. (Tate, 2019)

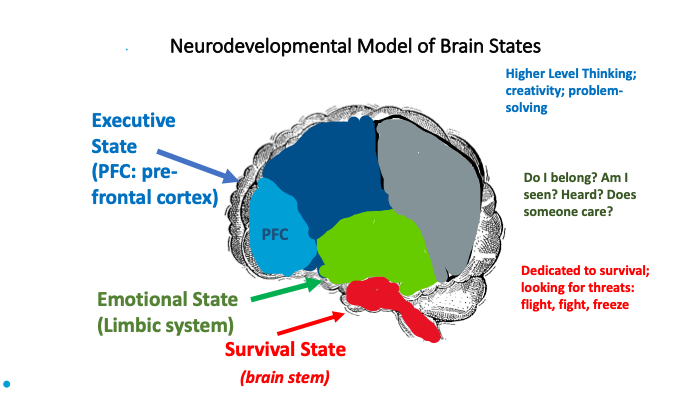

Students can be taught to self-regulate, but some require more compassionate understanding due to previous adverse childhood experiences. If we look at the neurodevelopmental model as described by experts like Bruce Perry (2020), Bessel van der Kolk (2014), and Becky Bailey (2011), we can gain an understanding of how behavior is directly influenced by the brain state a student is in.

Brain states can change moment to moment. As students enter our classrooms, they are in one of three states: survival, emotional, or executive. Translated into feelings: fearful, alarmed, or calm and alert. (Perry & Winfrey, 2021) If students are to self-regulate (which would make them less likely to behave badly), they must be able to identify how they are feeling and use strategies to help themselves alter their state if necessary.

Our job is to get students to their frontal lobe – calm and alert. If a student enters the room dysregulated or becomes dysregulated at any point, they are unable to get to the frontal lobe to learn. Frustration, fear, or anger take over and shut down communication to the executive level of the brain.

Students will respond to our regulated brains

The first thing to remember in this situation is that only a regulated brain can help a dysregulated brain. Co-regulation is key. So if the student has frustrated you, angered you, or made you fearful – and we all have experienced this in middle school settings – you will not at that moment be able to help the student regulate. You will be reacting to their behavior.

This causes you to say or do something that you would not do under ordinary circumstances, which can make matters worse. One example is saying, “What is wrong with you?” The real question to ask, according to trauma expert Dr. Bruce Perry, is “What happened to you?”

It’s not easy to get ourselves to that second question when we’re experiencing a pandemic that is stressing everyone. But compassionate empathy during those moments leads you to regulate yourself first. Methods to regulate yourself might include getting a drink of water, a quick walk, deep breaths, sitting quietly for a few minutes (I know that this is not easy to do in the classroom…I count and breathe), or even text a friend.

Remember that emotions are contagious and if you can put yourself in a calm state, it will help the dysregulated child do so, too. This process may also help you understand how easily you became dysregulated and give you more emotional empathy for the student.

Traditional punishments may cause more trauma for our already traumatized students. Approaching students with your own brain regulated allows you to see the situation from their perspective and take action that is appropriate to their needs. The three steps supported by trauma informed experts are regulate, relate, and reason. Regulation occurs in the brain stem, relating in the limbic system, and reason in the PFC.

Once you are regulated, you can begin to coregulate, help your student regulate. This student is stressed, which can range from mildly stressed to terrorized. The experts tell us that they need patterned, repetitive, predictable routines and experiences. In the survival state these kids need something that speaks to their brain stem. Each brain state has a language. (Desautels, 2020). This is a very useful way of categorizing strategies to help regulate.

The language of the brain stem is sensation so helpful strategies include tapping, playing with fidget toys, breathing, repetitive movements, music, or simply petting a dog. (It is so helpful to have emotional support dogs in schools to allow students to calm themselves, empathize with special pets, and even practice forming a relationship!)

Once calmed, their brain state is at the emotional level. The language of the limbic system is feelings. Relational strategies include the 2 x 10 strategy, talking to a friend, working in teams, cooperative learning activities, check-ins, and simply asking students what they need to feel better. They need to know you care.

Getting to the prefrontal cortex is the ultimate goal. The language of the PFC is words. Journaling is one way to help students as they center themselves. But any activity that involves writing, speaking, or singing wakes up the frontal lobe.

Rituals and procedures support compassion

Providing choice is at the top of my list as I work with a dysregulated student. Getting up to the executive state takes effort, so at the point where the student feels calmer and has a feeling of belonging, why not then offer a choice as to what to do next related to content?

Lewis (2019) explains that students from adverse environments have slower brain development which can make learning more challenging. Perhaps this student can hone in on where they are in the learning process. I sometimes ask, “If there’s anything you know about ________, what is it?” From that point of reference we can build on more learning. The choice of a mixed media essay or an infomercial to show what they know may keep them regulated.

The most promising classroom environment is one in which you have set up many rituals and procedures in your classroom that help regulate all of your students. Music is always playing when my students enter the room. It’s the same song each day, repetition is good for the brain and helps to calm it. You can frame it as your class theme.

With a dozen or so rituals in your classroom, you can create an environment that is predictable. You won’t be able to calm all of your students as some bring more adverse childhood experiences than others. But the more students whose stress you can lower, the less likely there will be altercations among students.

Compassionate discipline calls us to action; some of those actions are much different from our usual vision of discipline. Showing compassion can go a long way in helping students recognize their own emotions and regulate themselves.

Keep these differences in mind

Punitive discipline: “Your behavior is terrible, if you don’t shape up then…”

Compassionate discipline: “I’ve noticed that you aren’t being yourself, is something wrong? How can I help you?” Or “Are you okay? I’m worried about you.”

The results are in. Compassionate discipline builds better relationships that lead to more motivation, more engagement, and more academic success!

She is the author of Social-Emotional Learning and the Brain: Strategies to Help Your Students Thrive (2020) and other ASCD titles, including The Essential 25: Teaching the Vocabulary That Makes or Breaks Student Understanding (2021 – see her article). Marilee can be reached at brainlady@gmail.com. Find all her MiddleWeb posts here.