Engage Students Using Positive Psychology

By Stephanie Farley

Evan took a seat next to me on the bench after our second class together, distractedly scratching a bleeding scab on his forearm. He sighed and began, “Look, Mrs. Farley, I’m sorry. I…”

Evan took a seat next to me on the bench after our second class together, distractedly scratching a bleeding scab on his forearm. He sighed and began, “Look, Mrs. Farley, I’m sorry. I…”

“It’s okay, Evan,” I interrupted, “you don’t need to apologize. Let’s just figure out how we can make class better next time. Clearly something wasn’t working today. What do you think that was?”

As Evan shared how he was distracted by his friends, his increasing intestinal discomfort, and his desire to make everyone laugh, it became clear that his antics during class were not just goofing off.

Evan truly wanted to impress me, his new 8th grade English teacher, by writing witty, fun stories. He couldn’t help that he had a super loud voice that everyone listened to or that his friends found him excusing himself to go to the bathroom hilarious. In just being himself, Evan was a magnet for drama. It was disruptive, but we’d work through it.

The Impulsive Years

Obviously Evan’s not the only kid to struggle with impulsivity. Luckily, the field of positive psychology offers a strategy for student self-management that I have used repeatedly in my middle school classes. The idea is deceptively simple: positive emotions increase attention and build resilience.

Researcher Barbara Frederickson first introduced this notion in 2001 with her “broaden and build” theory, published in the journal American Psychologist (Frederickson). The theory states that positive emotions “can momentarily broaden people’s scopes of thought and allow for flexible attention,” as well as “increase one’s personal resources, including coping resources” (Tugade and Frederickson 320-321).

Consequently, over time, people can use positive emotions to engage their attention and be resilient in the face of negative events. Rad!

Applying theory to practice, I planned my classes so that positive emotions were present every single day, with the specific intention of helping students like Evan improve his sense of well-being, focus, and ability to bounce back quickly from distractions.

My goal was to create experiences, either in the beginning of class or during the lesson, that kindled humor, curiosity, enthusiasm, and optimism as students learned the skills of English. Let’s take a look at how specific activities can engage one or more of these emotions.

Humor

Another day my teaching partner burst into my classroom with his guitar, singing a song we wrote about the students (I just supplied some lyrics; my teaching partner wrote the music, wrote additional lyrics, and sang). Of course the kids found the idea of a guitar-strumming teacher singing a song about them hilarious.

Lastly, a winning move is to have the kids teach you their slang and then adopt it. When I used the phrase “that’s fire” in a way that was slightly off, it reliably provoked laughter from every person in the room, as they were all in on the joke.

The positive emotion of humor was also used in research studies to help people self-regulate after ego depletion (Tice et al). This is quite helpful for teachers to know, as the demands of school mean that students are in a state of ego depletion fairly often!

A dose of humor, though, can help kids restore themselves to a neutral emotional landscape. You don’t need to be a comedian; you simply need to be willing to explore what tickles your students and then unabashedly go for it.

Curiosity

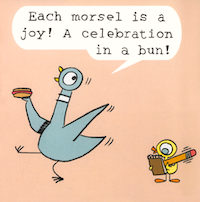

The character of Duckling in Mo Willems’ “Pigeon” series self-identifies as “a curious bird” (Willems), so I thought of Duckling as I planned my lessons: how could I present the skills or content in a way that would pique students’ interest in the same way Duckling was interested in hot dogs, bus driving, and all things Pigeon?

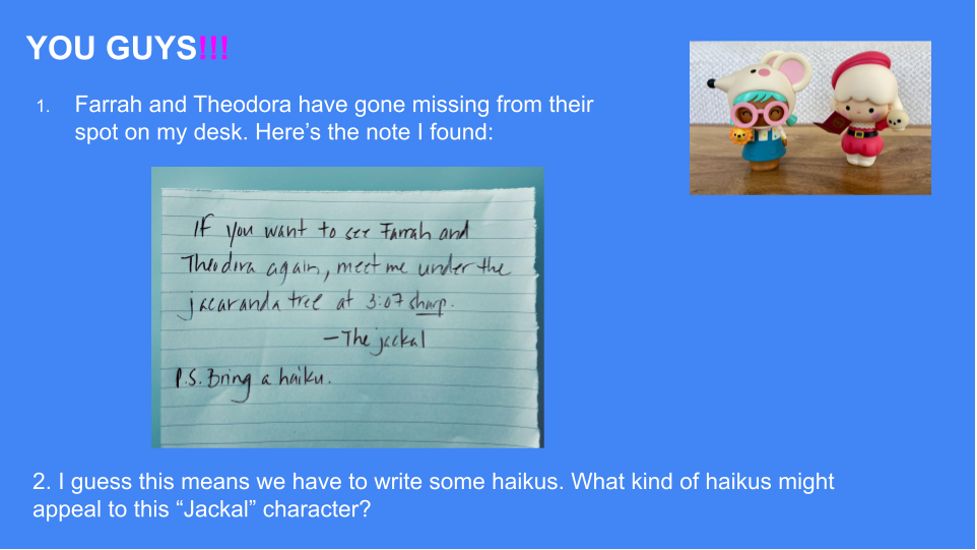

With that in mind, here’s a framing activity that I used frequently, changing the details but keeping the structure intact:

As you can see, I used the idea of stolen toys to kindle students’ curiosity – who would take Mrs. Farley’s toys? – and to create some energy around the idea of writing haikus. Once these haikus were written, of course, another clue would be provided about the toys’ location that required additional writing. In this fashion, I introduced the notion of form to the students, which was expanded upon later in the lesson.

When you frequently present students with positive emotional experiences such as an inviting opening activity, over time they learn that positive emotions are a conduit for engagement and focus.

Enthusiasm

As a teacher, I was keen to help students feel enthusiastic not just about my subject, but about their own ideas in the subject. I’ve found that choice is the best way to engage “enthusiasm mode,” so I gave my students choices in just about every aspect of class: what they wrote, what they read, and how they demonstrated their learning.

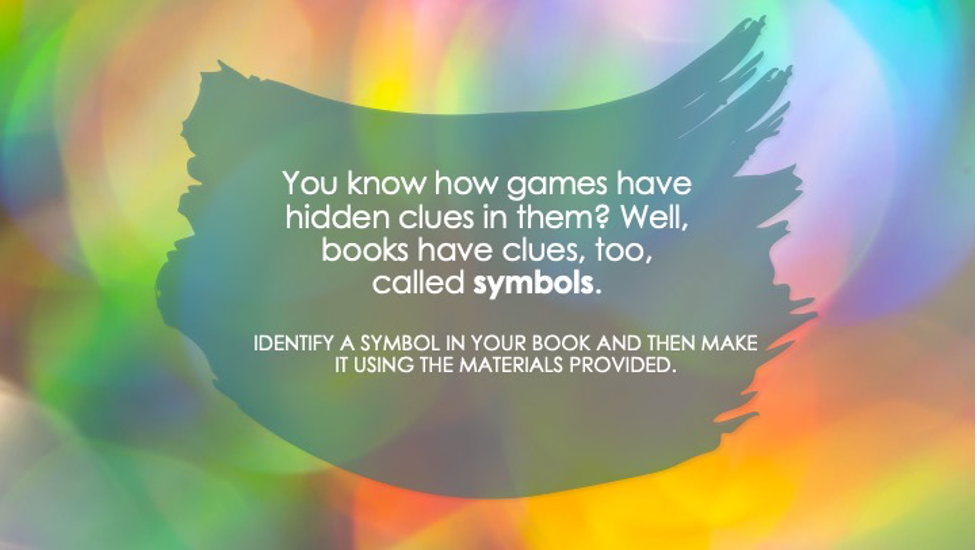

In the activity below, I capitalized on the enthusiasm-building nature of choice by asking students to identify a symbol in the novels they’d selected and then build it, using the craft materials I’d provided.

The ruckus that erupted after I asked students to complete this exercise was delicious: one could feel the air move as the kids dug books out of their backpacks, grabbed craft materials, and animatedly chatted with their friends.

Questions like “What does she mean by clue?” and “Does it have to be, like, an object?” drifted by, but they weren’t directed at me…they were directed at each other, which was the way I liked it! I wanted kids to find meaning on their own, without my biases tainting their interpretations.

While there were always students who got stuck on tasks like this, gentle questioning spurred understanding: “What is the main character’s goal? What is the obstacle to attaining that goal? Where is the main character now? What problem is the main character trying to solve?” (Here’s a teacher source for scaffolding tips/ideas about symbolism.)

As you coach students through this process of discovery, their resilience builds in proportion to their enthusiasm.

Optimism

Optimism is a vital ingredient in nurturing a growth mindset: students need to feel that they are capable of success. One way I helped develop students’ sense of accomplishment was by showing them easy ways they could improve their writing.

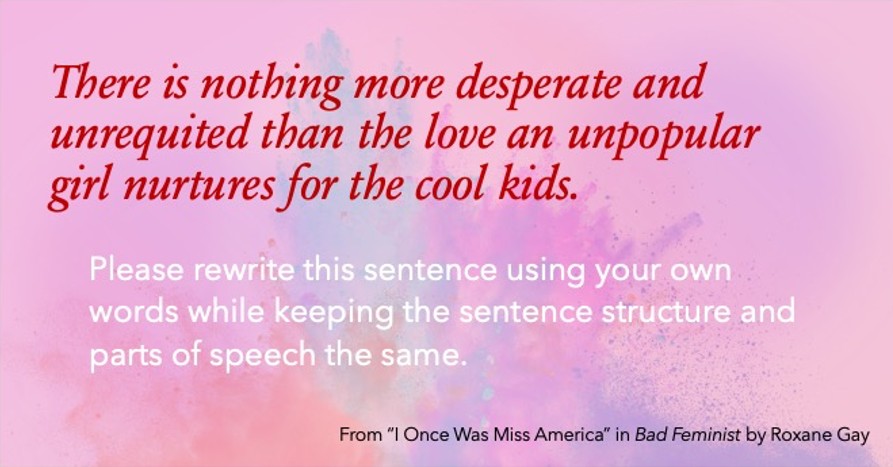

For example, we’d read short stories that showcased methods for putting together sentences that perhaps the students hadn’t encountered before. Then I’d pull a model sentence from the story (sometimes called a “mentor” sentence) and ask the students to rewrite it, using their own words but maintaining the structure.

Here’s an example:

In this activity, students had great conversations among themselves about parts of speech, sentence construction, and vocabulary. Additionally, they ended up writing terrific sentences! It’s the teaching grammar version of “show rather than tell.” And the best part is that these new sentence constructions showed up in their stories and essays.

When students see the path to improvement and discern their own progress in a skill, they feel optimistic. In turn, optimism improves focus and resilience.

Plan for the Long Term

How did any of this help Evan? The truth is that using positive emotions to build attention and resilience is a long-term strategy rather than a short-term one. While there wasn’t an immediate impact of positive emotions on Evan’s impulsivity, over time, after lots of moments of levity and curiosity and enthusiasm, Evan realized that my class was a place he wanted to be because, ultimately, it was pleasant.

He was welcomed, accepted, and encouraged in all of his strengths. He was allowed to tell jokes to his friends and then put the jokes that scored the most laughs in his written work. At the end of the year, Evan approached me in person to thank me for making English “the best class I’ve ever had.” As the 8th graders might say, so, yeah…my positive emotions strategy worked!

Intentionally introducing humor, curiosity, enthusiasm, and optimism into each class is a low-tech, high-impact method to build resilience and attention.

Works Cited

Tice, Dianne M., Baumeister, Roy F., Shmueli, Dikla, and Muraven, Mark. “Restoring the Self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 379-384, 2007.

Tugade, Michele M. and Frederickson, Barbara L. “Regulation of Positive Emotions: Emotion Regulation Strategies that Promote Resilience.” Journal of Happiness Studies, 8:311-333, 2007.

Willems, Mo. The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog, Hyperion Books for Children, 2004.

Stephanie’s first book, Joyful Learning: Tools to Infuse Your 6-12 Classroom with Meaning, Relevance, and Fun, will be published in April, 2023. She has created professional development for schools around reading and curriculum and coaches teachers in instruction, lesson planning, feedback, and assessment. Visit her website Joyful Learning and find her other MiddleWeb articles here.