Facing Up to Cultural and Religious Bullying

Is bullying in schools a social pandemic we need to take more seriously? Utah teacher Laleh Ghotbi makes a compelling case that educators and parents can do more to protect children.

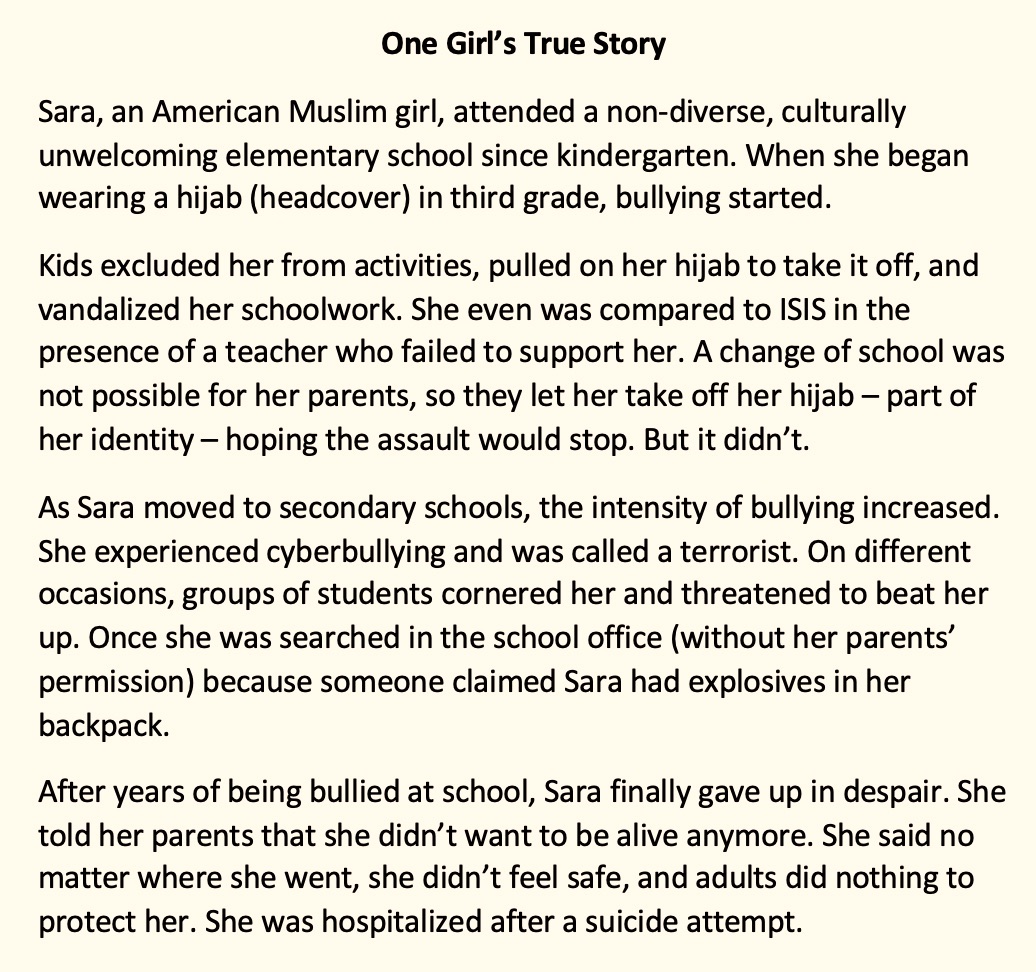

Bullying is defined as a repeated misuse of power that results in physical, social, and/or psychological harm in the victim (NCAB). While such behaviors are not acceptable and regarded as disrupting in the public eye, bullying is very common in schools and among kids from all age groups.

Bullies often target anyone who is different from the majority, such as students with physical or mental disabilities (facts), kids from low socioeconomic backgrounds, LGBTQ students (data), racial minorities like students of color, or students with different religious beliefs (story).

The behavior can start with verbal abuse including name calling and teasing and progress to the use of violence against the victims. These incidents happen more often in places with less adult supervision; for instance, bathrooms (story), playgrounds (study), school buses (data), or on the internet (data).

The negative aspects of bullying can be so severe that the victim may see no way out but taking his/her/their own life (story). In Utah, where I teach, suicide is one of the leading causes of death in youth ages 10-17 and bullying is one of the main risk factors.

According to the Utah Department of Health (UDOH), youth who are being bullied consider attempting suicide at a higher rate than their peers who have not been bullied. UDOH findings show a 141.3% increase in suicides among Utah youth aged 10-17 from 2011 to 2015, compared to an increase of 23.5% nationally.

We cannot undo the despicable things that happened to Sara, but there are many kids like her who need our support.

A feeling that there’s nowhere to turn

Kids who are being bullied often feel anxious, worried and scared, and in some cases are not willing to talk about the problem because they believe no one is able to stop it or cares enough to protect them.

Bullies are not always students. In some cases the bully is a teacher or staff member (story) which makes the problem more unbearable for the victim. The victims of bullying may offer any excuse to avoid school and not have to face their bullies. For them, going back to school means being shoved against lockers, humiliated, labeled as weak and incompetent, named as terrorists (immigrants) and gang members (students of color), and being physically injured.

Often, the traumatic effects of being bullied continue long after the bullying has stopped. Academic failure, school dropouts, depression, self-harm, suicidal ideas, drug abuse, and countless hours of therapy (if parents can afford it) are only a few examples of what victims and their families are dealing with.

The seriousness of this problem is even more evident when we look at the lives of students who became “school shooters.” According to Secret Service data, “For most of the attackers (n = 34, 83%), retaliating for a grievance played a role in their motive. For nearly two-thirds of the attackers (n = 25, 61%), it appeared to be their primary motive.” The Uvalde shooting – one of the more recent school massacres – was committed by an 18-year-old who was bullied in school for his speech impediment. (story)

We all share responsibility for solving this national problem

We must be alert to our children’s cries for help and protect them against the adverse consequences of bullying. Educators can do more to increase awareness among colleagues and community leaders and seek new ways to take action on this issue of pandemic bullying in our schools.

The movement against bullying starts at home. As parents, we need to teach our children to be more compassionate, accepting, and understanding towards differences. We should set a good example for them and model the behavior we expect by not talking down and degrading any minorities (racial, religions, ethnicity, color, gender, and sexuality).

What educators can do

As teachers, we have so much power to put a stop to this hurtful behavior. Fostering a sense of community in our classrooms – creating a more welcoming, safe, and inclusive learning environments for our students – is a great start. Getting to know each student better, building a positive relationship, and showing them love and respect regardless of their differences is something all our students need to see us doing.

As some states and localities adopt laws and policies that are likely to encourage division, educators must speak out. We need more classroom projects and school programs that emphasize the importance of diversity and how it creates a stronger community, empowering our students to be proud of their backgrounds, and to appreciate who they are.

Policy makers need to allocate more funds to schools so they can support students’ mental health and wellbeing by hiring well-prepared school counselors, implementing bullying prevention strategies, and inviting motivational speakers to boost our students’ self-esteem.

And we all need to hold social media accountable for spreading hatred against minorities and people of color. “The Holocaust did not start with the gas chambers, it started with hate speech against a minority.” (UN. News)

Let us plant seeds of kindness, tolerance, and acceptance so we can witness our children growing up to be mindful and compassionate adults who care for others and focus on our common grounds rather than our differences. A nation divided cannot stand.

Editor’s note: Three articles linked to this story lead to the Washington Post which (like many daily newspapers) has a pay firewall. The Post states that they allow visitors to read a small number of articles for free each month.

Laleh Ghotbi is currently a 4th grade teacher and lives in Salt Lake City with her husband and their two children. She is also a member of Hope Street Group and a Utah Teacher Fellow. Laleh began her teaching career in 1992 in Iran, where she taught in middle and high school for seven years and worked as an academic coach at the school district for the next two years.

Laleh came to the United States with her husband and their 8-year-old son in August 2000. Since then, she has earned two master’s degrees – a Master of Science and Technology-Biotechnology from the University of Utah, and a Master of Arts in Teaching from Westminster College where she graduated with honors and was chosen as the 2017 commencement speaker.

I really liked this. I experienced bullying my whole life as a child, and seeing this made me feel less alone

I had to deal with a bully as a boy scout. I wrote a story about it.

“The Bully of Lakewood or How Inner Strength Won The Day!”

http://bvj.com/bully/TheBullyOfLakewood.html

This is my first e-book.

“Thank You!” for the invaluable content of your blog.