Here’s How to Get Kids Talking about Literature

Classroom teacher and multi-book author Marilyn Pryle teams up with middle school educator Sharon Ratliff to help our readers explore Marilyn’s Reading Responses strategy – a technique to (finally) get students responding to literature at a deep level.

By Marilyn Pryle and Sharon Ratliff

I am also deeply heartened by the response of teachers who try using RRs in their own classroom. They often tell me it’s the technique that finally got their students responding to literature in a genuine and invested way.

This feedback confirms what I believe: Teachers want to create a space for their students to speak with authenticity and agency. What I also believe is that the RR method gives teachers agency and lets them use their expertise in authentic ways.

The RR Method Is Simple

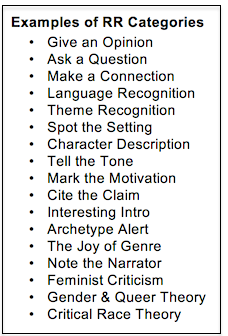

After reading a text, students write a response of no fewer than five sentences, including a cited quote from the text. They must categorize their response using a category from a list that they’ve received. Categories include Spot the Setting, Mark the Motivation, Tell the Theme, Find the Foreshadowing, Give an Opinion, and so on. Finally, their response must have an original thought; they can’t only summarize.

That’s it. Every time students complete an RR, they must have an original thought, a cited quote, a category, and a minimum of five sentences (this minimum can be adjusted slightly up or down depending on your class).

It is simple and direct. And those are the criteria I check for, plus one extra criterion of doing your best work. I grade my own students’ RRs on this five-point rubric. For a more in-depth description of this process, and to see some examples, visit my MiddleWeb article This Strategy Promotes Real Reading Discussions.

Why Do RRs Work So Well?

The magic comes in two ways: first, in the repetition and practice of the method, and second, in the in-class discussions afterward.

In my class we do these three to four times a week. This means that students habitually practice having an original thought and supporting it with a cited quote, as well as metacognitively analyzing that thought, on a regular basis. In addition, they are writing, writing, writing. The RR method is a continuous low-stakes exercise in writing fluency. Although I may discuss grammar in a student’s RR when appropriate, I do not grade for it.

In addition, students can be WRONG in an RR! Completely, 100% wrong. And they can still receive full credit for the work provided they have five sentences with an original thought, cited quote, and category. Slip-ups happen sometimes. When they do, the records will get set straight in the in-class discussions (with either me or a small group of their peers). After all, we don’t want anyone leaving class with misinformation about a text.

Think for a minute what this communicates to the students: It’s okay to be wrong. It’s okay to take intellectual risks. It’s ok to read something and not fully understand it. If we want to create lifelong readers and critical thinkers, these are the messages we must impart. The right / wrong dichotomy that students live with throughout their academic career often results in meek, disengaged readers who have been trained to look to an expert for “the right answer.” This type of thinker does not make for a strong citizenry.

How the RR Activity Plays Out in Class

In class students discuss their RRs in small groups while I visit each student for a one-minute check and conference about what they wrote. (Students also have some kind of additional activity to do after discussing their RRs, so they stay engaged with the text as I visit everyone individually.)

The mini-conferences give me a chance to connect with each student, be present to them, and help them with whatever they need in that moment. I won’t know what they need till I get to their desk, but options range from text interpretation, metacognition, grammar, pronunciation, answering a question they have, or even something personal that might come up. It gives me a chance to respond to the student as well as respond to their thinking.

As the years go on, I appreciate this simple method more and more. It is the bread and butter of my classroom. Sure, we do all the other Englishy stuff – we write in different genres, act out scenes, play Kahoot, have tests, do creative projects, and all the rest. But RRs are how we process texts, and the results are amazing. Since it involves genuine student thinking, I am always intrigued, often surprised, and never bored. Each day, I know the chunk of text we’re going to talk about, but I don’t know how we’re going to talk about it. The students take the lead.

I present to districts about RRs often, and connect with teachers all over the country. Last summer, I had the pleasure of speaking in Katy, Texas to both high school and middle school teachers there. One seventh-grade teacher, Sharon Ratliff, reached out to me after to say how excited she was about trying Reading Responses in her classroom.

What I love about hearing from teachers who try using RRs is the ways that they make it their own and adapt it for the students who are sitting in front of them. Ideas have included color-coding, inventing new categories, having category stations, and even letting students draw – the possibilities are endless!

I‘ve asked Sharon to share some of her ideas here.

RR Ideas for the Middle Grades

✻ Use the writing community in your classroom and start small. Begin by using mentor texts and have students write responses together.

✻ Give a Limited Menu related to the specific objectives you are covering for the next month. For example, in Texas, teachers code our TEKS objectives to the curriculum. TEKS then correspond to reading response categories.

✻ Write with Your Students: The results are twofold: an automatic book talk is built in about what you are reading and students get a peek at what you are thinking as a reader.

✻ Gradually Introduce the Process: After introducing students to the practice of reading responses at the beginning of the year, assign them responses for homework. Students are introduced to a new category or two on Monday with a menu of 4 to 5 reading response choices that have been introduced previously. Then students come to class on Thursday or Friday with their reading responses. (Note: Having students submit all reading responses electronically is beneficial because it gives an accounting system for responses and it’s easy to project various responses for other classes to view.)

✻ Celebrate or Share Responses: Try these Response Stems. For Specific Categories, tweak response feedback even more.

✻ Have Students Collaborate: You can extend Reading Responses into a group writing activity to incorporate more discourse. As an example, try this plan.

✻ Smooth Out Sentences: As students grasp writing RRs, introduce embedded quotes. We discuss how readers have not necessarily read the article or book they are responding to, so it is important to write a lead-in to the quote. Our motto is “No lonely quote.” Key evidence needs to be introduced using a transition, a lead-in, and then the quote.

To further illustrate the impact of using a lead-in for evidence, I use a basketball analogy. Most plays in basketball are “set up”— players don’t just grab the ball and make the shot. There is a strategy and set-up to support the “basket” which is the evidence used in an RR. As students compose RRs, they are surprised at how much their writing progresses simply by using the “No lonely quote” motto.

As teachers, we often feel like Sam I Am; however, by using specific strategies with reading responses, students will write responses on a boat with a goat or on a train and a plane! These strategies I use with my middle grades learners will help build student confidence to see that reading responses are not daunting, and are an excellent way to think, read, and write about various texts.

Your Next Moves

(Marilyn) If you’ve been thinking about trying Reading Responses and have been wondering where to start, or if you are intrigued and want to know more, read all the articles about RRs here on MiddleWeb.

You can also visit my website for a free starter pack, and see my book, Reading with Presence, for an in-depth explanation about how RRs work and ways they can be used in the classroom.

This spring, fellow Heinemann author and seventh-grade teacher Rebekah O’Dell and I recorded a podcast about using RRs that you can listen to. And don’t hesitate to reach out to me with questions! Helping students – and teachers – find more voice, choice, and authenticity in their work is my passion. Reading Responses have been the vehicle for me to do so.

Marilyn’s most recent book is Reading with Presence: Crafting Meaningful, Evidenced-Based Reading Responses (Heinemann, 2018). Learn more about her at marilynpryle.com and read other articles she’s written for MiddleWeb.

Sharon Ratliff (@sharondratliff) is an English teacher at Seven Lakes Junior High in Katy, Texas. Before stepping into the mysterious land of middle school, Sharon taught upper elementary in Texas and Florida, and with the Department of Defense. Sharon enjoys developing curriculum and discovering reading and writing techniques that empower students in real-life applications.