Teach Questioning Skills to Spark Self-Directed Learning

Welcome to our new series on how to get the most learning out of classroom questioning. Author and questioning expert Jackie A. Walsh joins two educators from the Dallas public schools – instructional coach Emily Brokaw and content teacher Anna Salazar. In this first installment, the trio explores ways to use questioning to strengthen teaching practice and empower students to become self-directed learners..

A MiddleWeb Blog

By Jackie Walsh, Emily Brokaw & Anna Salazar

I used to think the primary reason for improving questioning practice was to increase student engagement and move thinking to higher levels. I also believed that if we teachers improved our questioning practices, we could achieve this goal.

Through 35 years of partnering with teachers to enhance questioning practice, I’ve learned that these are important but not the essential reasons for questioning. Now I know the principal purpose for quality questioning is to generate dialogue consisting of feedback that students and teachers can use to move learning forward.

I also know that if we want to make questions count, it’s not enough for us to improve teaching practice. It’s essential that we teach our students new roles and accompanying skills that will enable them to be full partners in their learning. These are the key premises of my book Questioning for Formative Feedback (ASCD, 2022).

Earlier this year I noticed recurrent tweets posted by Emily Brokaw (@EmilyBrokaw2), an instructional coach in Dallas (TX) ISD. Emily’s tweets featured teacher use of practices I recommend, with particular emphasis on increased student responsibility for learning through questioning and feedback.

I reached out to Emily to learn more about the job-embedded professional learning she was facilitating at her school. This led to an ongoing virtual dialogue which expanded to include social studies teacher Anna Salazar. From our collaborative conversations emerged this Making Questions Count blog for MiddleWeb – shaped as a 5-part conversation among the three of us to explore issues related to the transfer of best practices in questioning and feedback to the classroom.

For this first installment, I asked Anna and Emily to think back on their journey – taking a 30,000-foot high view. In future posts, we’ll zoom down to focus on specific teacher and student behaviors they targeted to enhance questioning and feedback for their students.

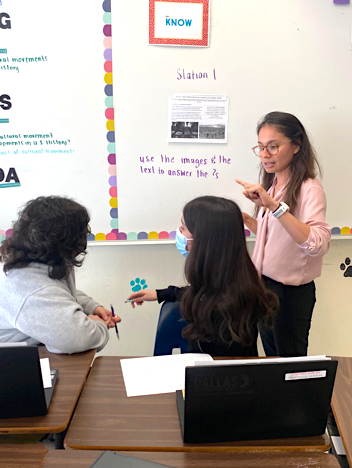

Anna Salazar: Creating a Culture of Questions

Jackie: Anna, you’ve shared that increased student understanding and use of questioning, feedback, and learning is a process that requires persistence and practice over an extended period of time. What are some of the lessons you’ve learned from your experience with your students?

Anna: If a teacher does all the talking, who’s doing the learning? When I asked my students “what does a learner look like?” they often said “learners look like they always know the answers, they follow the rules, and they’re probably quiet.”

My initial challenge was to partner with my students to change this perception about their roles as learners. The goal was to develop new mindframes based on these beliefs:

- Questions are more important than answers.

- Not knowing is a condition for learning.

- Active participation in classroom dialogue facilitates learning for all.

I also strongly believe that learning happens through intentional design of formative lessons and through teacher-student co-creation of a learning environment in which they become comfortable with these new mindframes.

Learning is not left to chance; it happens by design. I always envisioned having a classroom where students were engaged and participating in discussions, but I’ve learned through experience that it’s first necessary to intentionally design lessons that empower students.

I started by providing question stems to students to support them in asking their own questions. They learned how to form and ask questions both to clarify and to extend their learning.

It struck me almost immediately that our learners were hungry to find opportunities to engage in their learning. Brandon, a freshman, observed that “In all my middle school years, I never got to have a chance to ask my own questions. I just always had to answer my teachers’ questions. Now, I get to ask the questions, and that helps me understand.” Together we created an environment that encouraged students to be actively engaged in their own understanding.

As I moved to creating a more dialogic classroom, I recognized that I would have to shift the way I taught and reframe my role as an educator. I began to focus more intentionally on three teacher roles (Walsh, 2022):

- lesson designer,

- learning facilitator, and

- culture builder.

Instead of asking a myriad of sometimes unrelated questions, I began to focus on preparing a limited number of quality questions that would center student thinking on identified learning goals.

As the facilitator, I set the stage for learning by ensuring clarity, providing time for listening and interpreting student responses, and posing follow-up questions as the primary form of feedback to students. None of this would have been possible without first co-creating a classroom culture with my students where they felt safe and valued and one in which they owned their learning.

As I continued to encourage student use of question stems, I noticed an increased eagerness to participate. Mistakes were welcome, “a beautiful oops” if you will, as students began turning their misconceptions into questions and seeking feedback to clear up any misunderstandings.

Because students are almost always at various stages in their learning, some were already able to see relationships and to pose questions that deepened their learning and the learning of others.

The journey to creating a classroom centered around asking questions was not easy. Somewhere along their educational journey, some of the older students had either forgotten how to ask questions or had become afraid of asking them. Creating this new classroom culture required intentional work on my part. However, I did not accomplish this alone. I began by providing my students with the skills and opportunities to co-create this learning culture. It became a partnership.

Coaching Reflections: Emily Brokaw

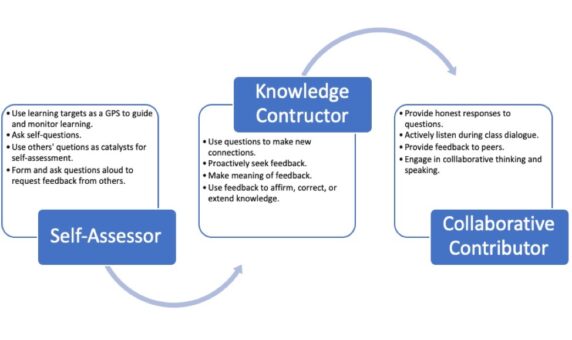

Jackie: Emily, we’ve talked about the value of being more explicit with students about their roles and responsibilities as learners. Can you connect the development of Anna’s students to the three student roles I identify in Questioning for Formative Feedback?

Emily: The development of students’ identities as learners that Anna describes did not happen by accident. Instead, this resulted from her intentional cultivation of specific mindframes about what it means to learn – and from her activation and support of the three key roles you associate with self-directed learners.

► Student as Self-Assessor: Anna encouraged students to use learning goals and success criteria to monitor their progress toward mastery. She emphasized that clarity regarding “where they’re going in their learning” and “what success will look like” is essential to self-assessment, which involves question-asking when we’re confused, use of teacher and peer feedback to self-correct, and being able to determine when we are ready for next steps.

The skills students developed in self-assessment supported “listening and speaking about their learning” that enabled “students and teachers [to] realize what they do deeply know, what they do not know, and where they are struggling to find relations and extensions.” (Hattie, 2023). The work we’ve done in our school with teacher clarity and student questioning has provided students the knowledge and skills to monitor and direct their learning.

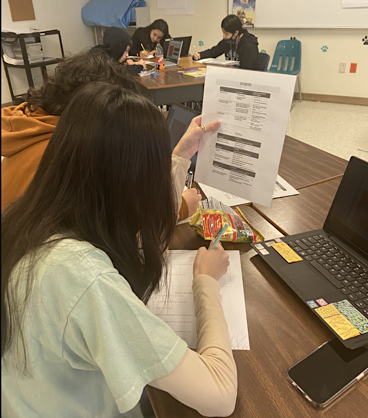

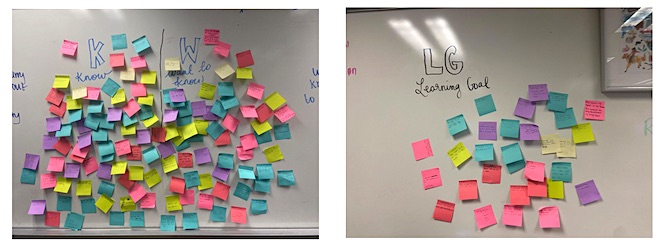

Using a modified KWL chart allows Ms. Salazar’s students to understand what they already know about a topic, frame their own questions and set learning goals for themselves.

► Student as Knowledge Constructor: Skills in self-assessment have been foundational in student acceptance of their identity as learners responsible for mastery of the content. By centering questioning and dialogue, Anna created independent learners who “recognize that no one can ‘give’ them knowledge – that they are responsible for engaging in the cognitive processes that support construction of their own understanding.” (Walsh, 2022).

Two prerequisites for students to act as knowledge constructors are content that is engaging and a culture in which they are comfortable grappling as they work to make personal meaning and connect new to prior knowledge.

► Student as Collaborative Contributor: Learning is accelerated through student-to-student dialogue. Anna’s students routinely asked questions of one another and provided honest feedback. They felt safe in taking risks, sharing their thoughts, and asking questions because of the norms they developed and the strategies and protocols their teacher provided to structure their interactions. The resulting class dialogue was an important contributor to individual student’s self-assessment and knowledge construction.

Jackie: Anna referred to three roles she performed as she became more explicit with her students about the use of questioning and dialogue to generate feedback for learning. As her instructional coach, I know you had opportunities to both collaboratively plan and reflect with her and also observe in her classroom. What stands out to you when you reflect on her success?

Emily: John Hattie often notes that it’s not so much what teachers do but how they think about what they do (Hattie, 2023). Anna Salazar views learning goals as a mechanism for student self-assessment and monitoring. She considers student questions to be windows into where they are in their thinking and learning.

Anna understands that feedback is valuable only when learners understand how to use it to self-correct and decide “where to next.” These mindframes provided the why behind her actions related to the three teacher roles she mentioned above.

► Teacher as Culture Builder: One of the most important jobs of a teacher at the beginning of the school year is to create a collaborative, open, respectful and equitable classroom culture (Walsh, 2022) and then subsequently tend to it throughout the year. Evidence of Anna’s attention to culture-building was particularly apparent when I observed class discussions. I was struck by the ease with which students questioned and responded to one another and with their desire to help when a peer was struggling.

I also noticed that students were not embarrassed by not knowing, but understood that wrong answers were a part of learning. Remarkably, students shared talk time and encouraged classmates who were not participating. Anna and I believe that her success in developing student ownership for their learning rested on the strong classroom culture that she and her learners co-created.

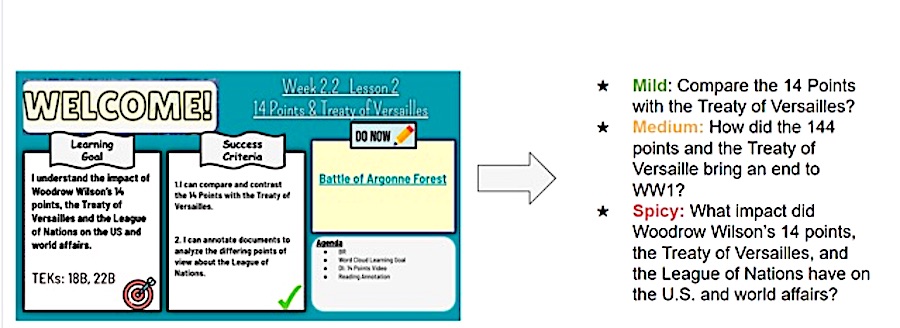

► Teacher as Lesson Designer: As you’ve noted, Jackie, “student engagement in formative activities occurs when teachers plan for this to happen.” (Walsh, 2022). A large part of the success we’ve seen in Anna’s class this year is due to the planning of aligned learning goals, success criteria, questions and learning experiences. Our principal often remarks that the game isn’t just won on the court or field, but rather it’s also won at practice. The time we’ve invested in planning lessons with aligned focus questions and response formats creates opportunities for quality questions that generate feedback that can be used formatively by students and teachers alike.

Example of pre-planned focus questions aligned to a learning goal and success criteria of a lesson in Ms. Salazar’s class. Click to enlarge.

► Teacher as Learning Facilitator: We all know that planning is essential, but not sufficient, to student engagement and learning. During live instruction, Ms. Salazar’s own mindframes led her to notice whether or not students were moving along the learning progression. They also prompted her to use follow-up questions as feedback and scaffolding to keep the cognitive lift with the learner. She worked with her students to incorporate think times 1 and 2 which created space for teacher and students alike to listen attentively, interpret a speaker’s meaning, and prepare a response to serve as effective feedback.

Emily: Whether engaging in coaching conversations or classroom observations, I was struck by Anna’s intentionality and consistency in adhering to these practices and in developing her students’ capacity to be full partners in their learning.

Next: Creating and sustaining a learning culture

Jackie: As an author, I’m excited and gratified when educators move concepts and strategies from one of my books to actual practice in classrooms across a school. Emily and Anna’s successful use of these strategies reinforces that of the 14 teachers who collaborated with me while I was writing Questioning for Formative Feedback and whose work is featured in 21 videos we created for the book. Emily and Anna will continue sharing their experiences in this blog series.

During future installments of the series Making Questions Count, we’ll take a deep dive into the strategies, tools, and techniques associated with each one of the student and teacher roles highlighted in this blog. Our next blog will spotlight skills and strategies associated with creating and sustaining a learning culture to support questioning for formative feedback.

See the entire Making Questions Count series here.

References

Hattie, J. (2023). Visible Learning: The Sequel. New York: Routledge.

Walsh, J.A. (2022). Questioning for Formative Feedback. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Walsh, J.A. (2021). Empowering Students as Questioners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Emily F. Brokaw is a Campus Coordinator at Molina High School in the Dallas, Texas Independent School District where she leads her campus’s work with Assessment for Learning and helps to create the conditions for all students to become lifelong learners! Prior to this role, she was a social studies teacher for six years. Emily has a Masters in the Art of Teaching from Texas A&M University-Commerce and is currently pursuing a Masters in Urban Educational Leadership from SMU.

Anna K. Salazar is a U.S. History teacher at Molina High in Dallas ISD. She teaches in an Assessment for Learning classroom where she works to create experiences that empower students to be inquisitive and ask questions. Additionally, Anna supports new teachers to empower students to own their learning through intentional practices. She is in her fourth year in education and a member of the Innovation in Teaching Fellowship.