Using Poetry Pauses to Elevate Student Writing

By Brett Vogelsinger

It took a few more years of teaching to understand the truth of that sentence.

Back in sixth grade, my own poem was published in the elementary school newsletter. In high school, I worked on the literary magazine as an editor and writer and published a rather attention-grabbing poem about a zit.

In college I discovered the Poetry 180 project from former poet laureate Billy Collins, and in my first year of teaching we used many poems as mentor texts for our own work in writer’s notebooks.

So yes, when I started teaching, poetry was already “everywhere” in my own education and the experiences I brought to my students. But it was in the background. In my middle school classroom, like many others, poetry inhabited a small unit before a break, during National Poetry Month, or when the class needed a breather after we finished something big.

It took me years to realize that poetry can be the heart and soul of an English class AND that it can help students as they seek to meet almost any reading and writing standard.

We can use a poem to evaluate an argument, to model the structure of a narrative, or to distill our research. Some poetic structures can facilitate brainstorms, while others model punctuation or grammatical patterns repeatedly in a short space.

My recent book from Corwin Press elaborates on all of this and more. However, any teacher-writer will tell you that after a book release, an author’s eyes suddenly open to all the other things they could have included. In my case, those “things” are poems that would fit nicely into chapters of the book and into our classrooms this year.

So consider this article as a preview of the book AND an extension, appendix, or addendum of three “poems that got away.”

Most importantly, take a moment to notice that poems really ARE everywhere, for no matter the genre, when we encounter rich language and well-expressed thinking, we use the word “poetic” to describe it.

Try applying these three ideas for more poetic expression from your students this school year.

1. Helping students add depth to their writing.

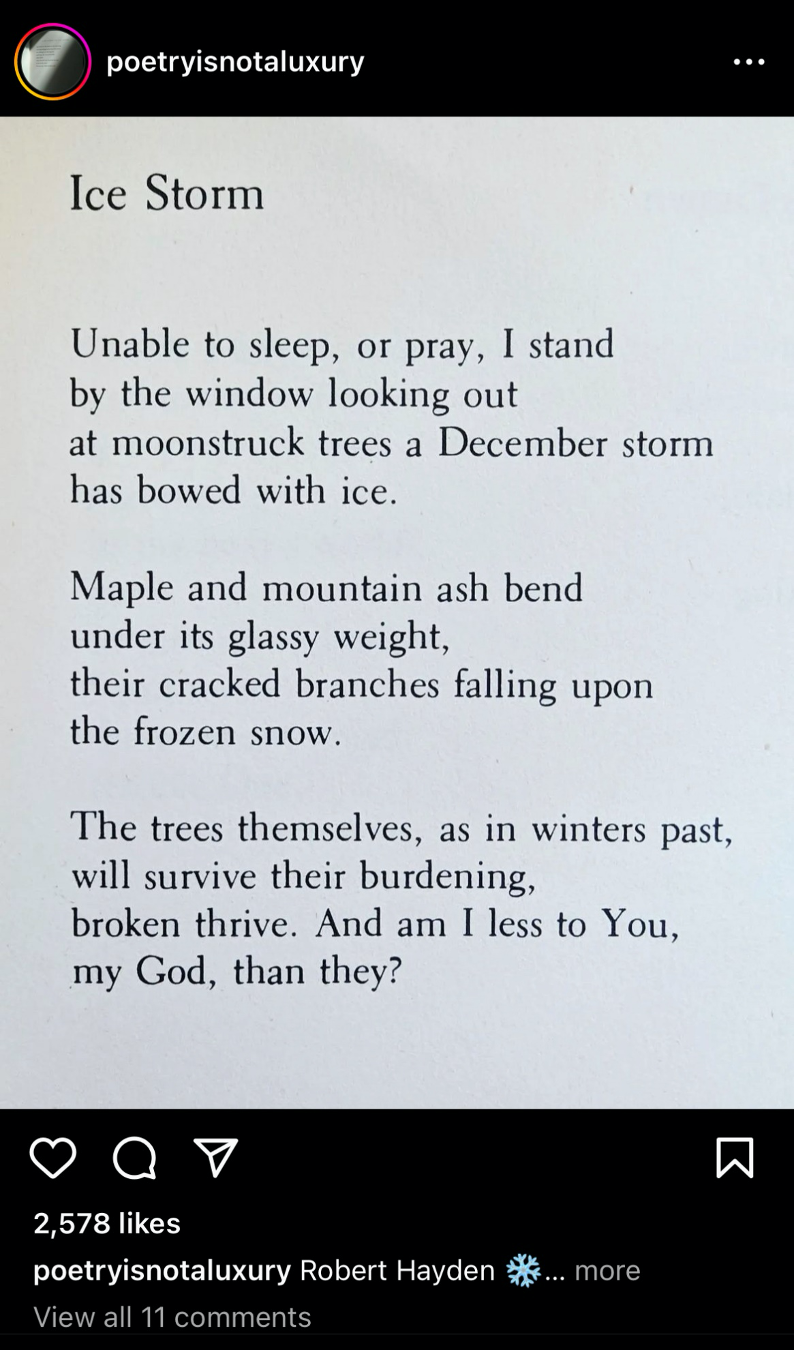

When people hear that I start English class with a poem each day, they often ask, “Where do you find all of the poems?” One of the answers is social media, and the Instagram account @poetryisnotaluxury does not disappoint. The other day they featured “Ice Storm” by Robert Hayden:

This poem has a clear and simple structure in its three stanzas:

Stanza 1 = the speaker tells you what he is looking at

Stanza 2 = the speaker shows you what he is looking at (with descriptive imagery)

Stanza 3 = the speaker illuminates meaning in what he is looking at and even asks a question

It would not take long for students to write a poem that mimics this pattern by looking at something else in nature, in the classroom, or in their own home. But think beyond that a moment. Doesn’t this model how to extend the development of an idea over paragraphs in an essay, not just stanzas in a poem?

Suppose students are writing an essay about a problem and a suggested solution.

In examining the problem, might students first tell what the problem is in a short paragraph, then show what the problem looks like with imagery, then illuminate why the problem matters in the world and what questions that problem provokes in the world? Many professional writers follow this same pattern in their articles!

Think of how much more poetic an essay can become with that approach, which we first discover in a short poem about bowed trees and human perseverance.

2. Embedding a simile in a personal narrative.

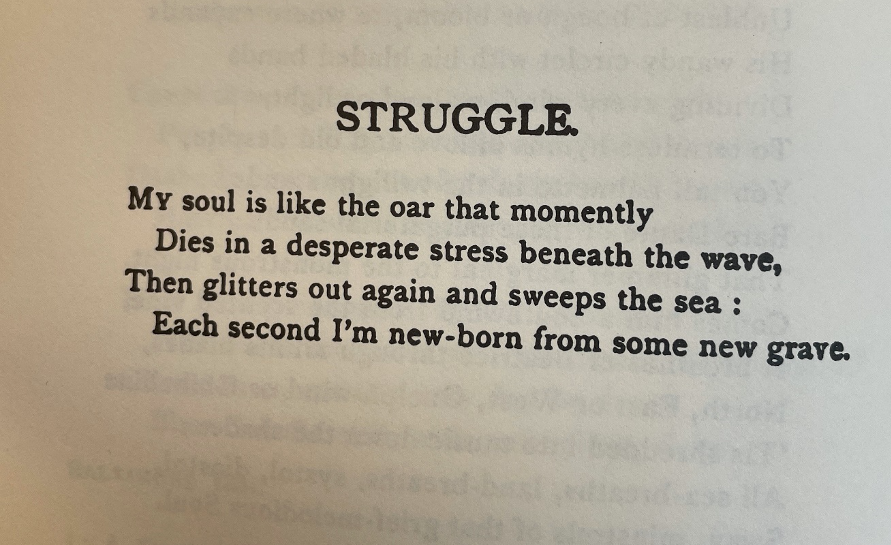

I found this poem in quite the opposite direction from social media: in the special collection of local history in the Atlanta Public Library. Notice how 19th century Georgia poet Sidney Lanier’s short poem “Struggle” might serve as a mentor text for students writing a personal narrative:

Personal narratives require what Nancie Atwell first called the “so what?” moment where students elaborate on why the memory mattered, how it affected them deeply. This poem can help them explore that a bit.

What if we asked students to define their “soul” using a grammatical pattern from this poem? This helps students use their own words while crafting something that sounds poetic, a line that is inspired by poetry but useful in a narrative draft.

After reading this poem and discussing it briefly, we can give students this frame on the whiteboard:

“My soul is like _________________________ that _________________________ then _____________________: Each second I’m ___________________________________.”

While every student can try this in their writer’s notebooks, not every student will end up with a line that is mellifluous or useful. That’s OK. Some will.

Other students will have exercised stretching their syntax with a bit of poetry: a win! When we make a practice of using poems to guide writers in all sorts of genres, it manifests in their writing in other lines, perhaps with a simile or a colon which they have now had the chance to practice.

3. Contemplating character before we analyze fiction.

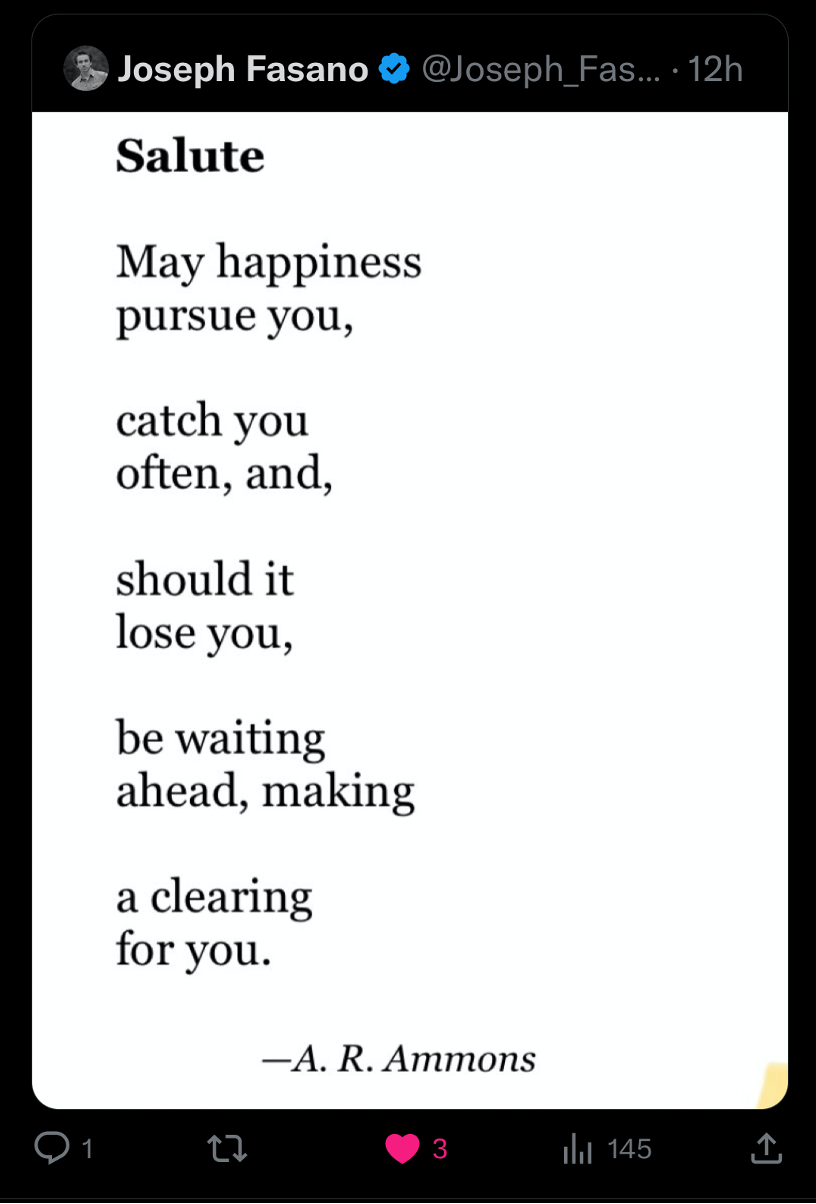

If you are active on Twitter and want to incorporate more poetry in class, be sure to follow Joseph Fasano for poems written by Fasano and others, poetry prompts to get you writing, and crowdsourced threads of favorite poems around a topic.

The poem “Salute” by A. R. Ammons is beautifully straightforward and helped students to analyze a character in a longer book we are studying.

After reading this poem, students can consider this prompt:

“Choose a character from the book we are reading right now. Write a short salute that your favorite character in this book might say, patterned after this poem. If your favorite character is villainous, it’s OK to write a short curse or malediction instead.”

This poem will not take long for students to write, plus it weds their interpretation of a character with their own creativity. As a follow-up, invite students into some more academic analysis with this prompt:

“Now write a paragraph that uses evidence from the text to prove that this would be a realistic salute (or curse) for this character to utter.”

Literary analysis of a character can be this engaging! All it takes is a creative angle on a short poem.

Sharing poems’ gifts with students

You may notice that all three of these poems in this post have positive themes, and this is something else that poetry can do for our classrooms. Heavy literary themes are an important part of English class, and so are those books our students might dub as “depressing.” But words also allow humans to heal, celebrate, motivate, and rejoice. Many poems do this, and incorporating them either into our writing units or into our daily practice can remind students of the many uplifting gifts of language.

I encourage you to make poetry a more fundamental part of your classroom. That may mean incorporating a poem of the day or a few select poetry pauses in the writing units you already teach. Let poetry be everywhere!

Read Kasey Short’s MiddleWeb review of

Poetry Pauses here.