Designing Our Lessons To Be Feedback-Driven

Welcome to our series on using carefully crafted classroom questions to accelerate learning. It’s a collaborative undertaking by a leading expert on questioning and feedback, working in partnership with a school-based teacher and her instructional coach.

By Jackie A. Walsh, Emily Brokaw and Anna Salazar

In our previous blog, we explored Teacher As Culture Builder. Here we turn to the critical role of Teacher As Lesson Designer.

Lesson design differs from lesson planning. While both are essential for an effective lesson, design is a creative process that addresses the learning needs of both students and teachers as they seek to achieve a given learning goal.

Jackie Walsh

Planning, on the other hand, focuses on the practical issues of organizing and managing resources to attain the goal. This includes text selection, practice opportunities, and time allocations. In my view, design is the fun part. Planning is its necessary partner.

What lesson design looks like

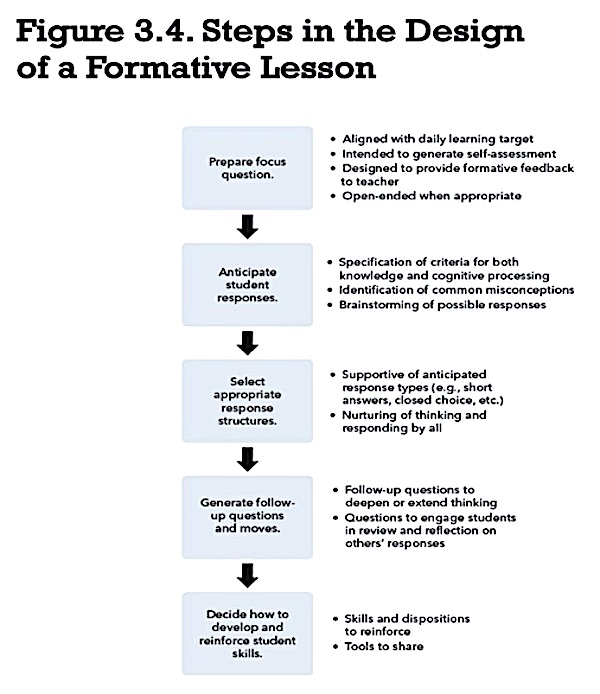

Design is essential if teachers are to leverage quality questioning in the generation and use of feedback during daily teaching-learning transactions. Daily learning targets are the anchor for this process that begins with the formulation of a limited number of focus questions.

Focus questions prompt students to retrieve knowledge and skills related to the question, readying them to respond orally to their teacher and/or classmates and to self-assess their progress. These student responses provide feedback teachers can use in deciding what to do next.

A general rule is to create focus questions that tap into student understanding at three points in a lesson: beginning, middle, and end. The intent of the initial question is to activate and assess background knowledge. The second question is to assess student progress toward the daily learning target at a strategic point in the lesson. A final question, which can be offered as a prompt for an exit ticket, serves to consolidate and assess learning at the end of a class.

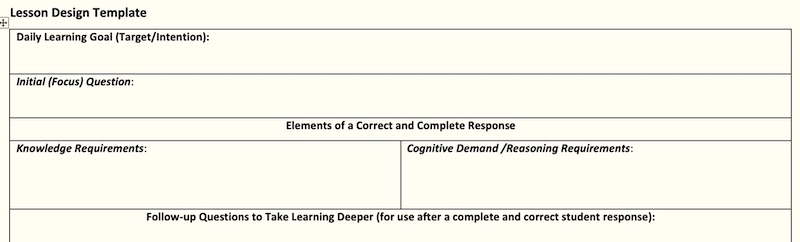

Lesson designers are clear about their expectations for correct and complete responses to the focus questions. They also predict incorrect and incomplete responses. This enables them to generate follow-up questions that assist students in identifying errors in their thinking and building correct understandings. As I’ve partnered with teachers to refine the question formulation process, they’ve found this lesson design template to be useful.

Designing for meaningful student responses

For each focus question, designers consider how best to engage all students in thinking and responding. One correct response from a student volunteer is not sufficient feedback to enable teacher decision-making about the next instructional move.

This is one of the reasons I argue against using hand-raising as the go-to response structure. Use of this method reinforces the “right-answer oriented” classroom, one in which students believe that the purpose of questions Is for someone (anyone!) to answer correctly. If students are to believe that learning is the purpose for questions, teachers must expect all students to use them for this purpose. A strategically selected response structure promotes this end.

There are an array of response structures that build accountability for listening and responding on the part of all and that advance peer-to-peer learning opportunities.

All-response systems are those which accommodate concurrent responding by all students. Traditional structures include work samples displayed on white boards, signaled responses, and choral responses. Electronic options range from simple clickers to select an alternate response – to apps such as Padlet, Mentimeter, and Jamboard that enable short responses for projection on a screen – to Google docs, Pear Deck, and Nearpod that accommodate lengthier, open-ended responses.

Non-electronic, collaborative response structures afford students the opportunity to support one another’s thinking and responding. Think-pair-share is a widely used such structure. More sophisticated alternatives use protocols to govern who speaks when and, at times, for how long. Among my favorites are Ink Think, Generate-Sort-Name, and Synectics.

Finally, teachers can turn to the Thinking Routine Toolbox assembled by Ron Ritchhart and colleagues at Harvard University’s Project Zero. Core thinking routines such as See-Think-Wonder, Think-Puzzle-Explore, and Connect-Extend-Challenge scaffold student thinking as they respond orally or in writing.

Teacher creativity comes into play as questions are formed, responses anticipated, and response structures selected in the quest to generate and use feedback to enhance the learning experience of a particular class of students.

Emily Brokaw

Emily Brokaw: Lesson design in the real world

Jackie: Emily, how do you engage the teachers you coach in the design of lessons that create opportunities for formative feedback?

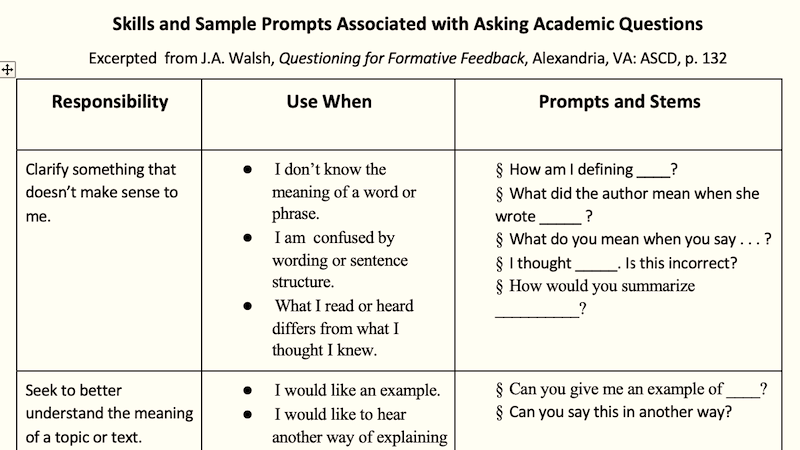

Emily: Many of the lesson design factors that I stress in my coaching sessions with teachers are the same ones you note as being essential to formative lesson design. These are embedded in the framework you offer in your book, Questioning for Formative Feedback. (Below – click to enlarge.)

During our planning and feedback sessions, I center thinking on three key processes that greatly impact student learning:

- First, establishing the lesson learning goal and success criteria which are rigorous and continually used by the teacher and student to drive learning.

- Secondly, using success criteria as a tool to plan higher-level focus questions. I encourage teachers to plan at least one focus question per success criterion as a way to assess and advance student thinking.

- Finally, selecting response structures that allow all students to respond to each focus question enables teachers to assess where each student is in their learning and to use student responses to move learning forward.

As teachers advance in their ability to design lessons centered around these three practices, I work with them to generate ideal student responses and anticipate possible responses revealing errors or misunderstandings.

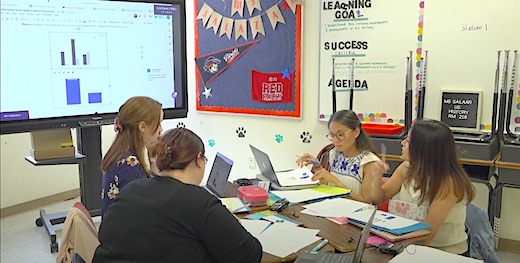

I’ve found that collaborative planning enables teachers to pool their experiences to identify incorrect or incomplete understandings. We’re then in a position to identify or generate follow-up questions designed to get behind the thinking that led to the misunderstanding.

Jackie, your examples of follow-up questions to use as feedback to students provide generic moves for teachers to consider. As time permits, we create follow-up questions that are specific to the concept embedded in a question. This generative thinking taps into individual and collective creativity and readies team members to facilitate student learning in real time.

Jackie: I know that you are partnering with Anna to support her use of these principles in designing formative lessons for her U.S. history classes. We are privileged that she is sharing how she and her students are incorporating questioning into their daily lessons. How did the two of you apply the principles you mentioned in the lesson segment she shares below?

Emily: Going into this lesson Anna Salvazar and I knew that the main goal was for students to be able to connect the problems of the Gilded Age to solutions developed during the Progressive Era. This would require learners to retrieve their prior learning about the Gilded Age while simultaneously connecting it to their new learning about the Progressive Era.

I knew of her interest in exploring strategies associated with the “thinking classroom,” including the design of a “thinking task” and the use of randomized groups. During our coaching session, we discussed other strategies that would strengthen students’ background knowledge and push their thinking. Included among these was the provision of a list of key vocabulary terms to maintain focus on key content.

We were also intentional about generating follow-up questions that she could ask the working groups while monitoring their learning and sustaining their “keep thinking.” Anna is an excellent listener and observer of student learning who is skilled in using questions to scaffold and provide feedback to students as they are in the process of learning. This design feature plays to her natural strength.

Anna Salazar

Anna Salazar: Designing for engagement and challenge

Jackie: This is an excellent example of how use of the design process can support student-driven dialogue. All of us have heard teachers lament the problems they encounter when allowing students to work in small groups. Anna, this design focus provided structures for small group conversations and supported intentional teacher monitoring and scaffolding. What was your thinking as you approached this design task?

Anna: The lesson design process involves intentional planning on how to engage and challenge students with content. As I thought more about creating a lesson that would involve students in deep thinking about the Progressive Era, I recalled a recent Edutopia article I’d read about thinking classrooms. Based on a book by researcher Peter Liljedahl, the focus was on math classrooms. I imagined how I might incorporate the 14 practices into this lesson design for my US History students. Each of the practices seemed easily adaptable across curriculums.

As I began the Progressive Era unit, I wanted to assess what the students remembered about the Gilded Age – specifically all of the era’s problems. I also expected them to generate possible solutions for the issues before we even looked at the Progressive Era – another opportunity to assess prior knowledge. This “thinking task” met Liljedahl’s criteria and served as the prompt for student dialogue.

I organized students into randomized groups (another practice in the thinking classroom) where they generated and jotted down all the problems they could remember from the Gilded Age. They were then asked to find solutions for the problems they listed using their prior knowledge.

Click for Academic Stems and Exploratory Stems charts.

As I designed this lesson, I planned for students to use their question stems to ask academic and exploratory questions to drive their own and their group’s thinking. They would also be free to pose their questions to me when desired. This design feature provided an additional opportunity for me to gather feedback about their learning.

Time invested in the design process did pay dividends. Students were able to identify key problems of the Gilded Age, including the political corruption, child labor, long working hours and unsafe working conditions, and nativism. My use of pre-planned questions supported them when they were struggling.

Jackie: Beginning a new unit or lesson with a prompt to activate prior knowledge is an essential feature of a formative classroom. As Anna’s lesson demonstrates, this enables students to make connections that anchor their learning in long-term memory and fill in gaps in background knowledge as needed.

Earlier I defined design as a creative process that addresses the learning needs of both students and teachers as they seek to achieve a given learning goal. This lesson from a U.S. History classroom illustrates how the creation of questions and determination of appropriate response structures advanced both student and teacher learning.

Students made connections that served as a foundation for engaging in deep learning in a new unit. The teacher learned about her students’ current level of understanding – what she could build on as she designed upcoming lessons – and the gaps she would need to fill. This is the essence of questioning for formative feedback.

See the entire Making Questions Count series here.

Jackie Acree Walsh, Ph.D. is an author and consultant focusing on quality questioning. Jackie is author or co-author of six books, two of which provide the basis for this blog series: Questioning for Formative Feedback: Meaningful Dialogue to Improve Learning (ASCD, 2022) and Empowering Students as Questioners: Skills, Strategies, and Structures to Realize the Potential of Every Learner (Corwin, 2021). Follow Jackie on X/Twitter @Question2Think. Find all of her earlier MiddleWeb articles here.

Emily F. Brokaw is a Campus Coordinator at Molina High School in the Dallas, Texas Independent School District where she leads her campus’s work with Assessment for Learning and helps to create the conditions for all students to become lifelong learners! Prior to this role, she was a social studies teacher for six years. Emily has a Masters in the Art of Teaching from Texas A&M University-Commerce and is currently pursuing a Masters in Urban Educational Leadership from SMU.

Anna K. Salazar is a U.S. History teacher at Molina High in Dallas ISD. She teaches in an Assessment for Learning classroom where she works to create experiences that empower students to be inquisitive and ask questions. Additionally, Anna supports new teachers to empower students to own their learning through intentional practices. She is in her fourth year in education and is a member of the Innovation in Teaching Fellowship.