Keys to Making Videos Comprehensible to MLs

A MiddleWeb Blog

Like many other young students, I loved the days when teachers would play videos to teach content.

Like many other young students, I loved the days when teachers would play videos to teach content.

I clearly remember once watching a clip about King Cyrus, the Persian king who freed the enslaved Israelites in Babylon and wrote a document to codify the rights of his citizens.

I remember the dramatic music, the slow panning over artistic renditions of Babylon, and the camera zooming into the Cyrus Cylinder, which the rights were written on.

Despite the popular opinion at the time that any screen would turn your brain to mush, it always seemed that I remembered more details when I watched these educational videos than when hearing lectures from my teachers.

Cyrus Cylinder. Source: Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net). Modifications by مانفی, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

As an educator now, I lean heavily on videos to teach students content in an engaging way. The visuals of explainer videos bring academic concepts to life – an advantage particularly helpful for multilinguals. Instead of my teacher talking to me about Babylon, I saw close up the ancient cuneiform etched into the hardened clay cylinder, something my teacher could not do even with the most detailed descriptions.

Explainer videos need explaining

However, despite their visual nature, explainer videos are also challenging for MLs because of the dense academic language, the rapid speaking pace, the large amount of content covered, and the extensive background knowledge required to understand them.

After years of trying to teach through these videos and refining my practice, I have settled on a way to use explainer videos that’s more effective for MLs.

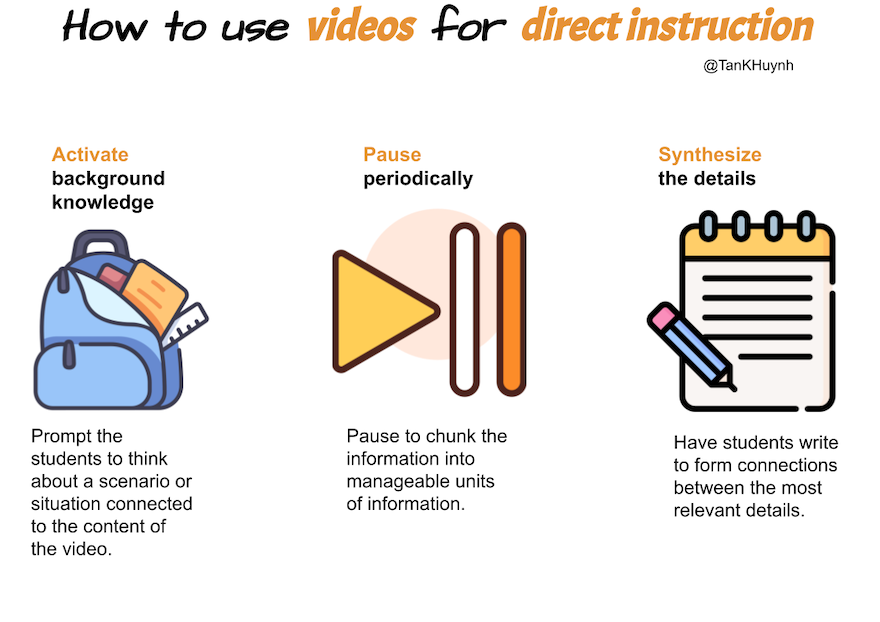

1. Activate background knowledge

Effective video instruction begins at the planning stage. Select the best video, which often:

• has lots of visuals

• does not have a “talking head”

• has speech spoken at an accessible pace

• is short (5-10 minutes)

If the video is quite long, select just a 5-10 minute section of the video to show students. Hour-long videos and documentaries are cognitively more demanding, and their effectiveness is lost on many MLs due to their length.

After you identify a video to use, determine the concept that this video teaches. Then think about a real-world experience that is connected to that concept. For example, when I taught a unit on ecosystems, I contextualized it around how Bangkok is sinking due to the destruction of its swamp ecosystem. A symptom of Bangkok sinking is the increasing number of floods in the city.

Therefore, before having students watch a video about land subsidence, which causes Bangkok to flood, I asked them when they had seen flooding in Bangkok or another place they have lived. This opening question activates students’ background knowledge about water surges much more than if I had just launched the video about land subsidence without context.

What’s the difference between activating background knowledge with a relevant question and asking a guessing fact-based question like, “Why is Bangkok sinking?” With the latter, students will simply guess at the answer and not actually remember an experience in their own lives.

For students who have never experienced flooding, I present a more inferential question instead, such as “How can floods be harmful?” In response, students can apply what they generally know about floods even if they have never seen them. Asking these types of Socratic questions helps students think about the content in the video so that new concepts can attach to something somewhat familiar, increasing engagement and retention.

2. Pause periodically

The least effective way to teach a video is to just play the video from beginning to end and then ask comprehension questions. The avalanche of details and the speed of delivery is overwhelming for MLs. There’s simply no processing time. Instead, I encourage teachers to periodically and intentionally pause the video at important details, which chunks the content into more manageable units.

A more effective way is to do the following before playing the video for students:

►Check to see if the speed and the subtitle functions are available. If they are, reduce the speed slightly.

►If the subtitles are only in English, please turn them on.

►If they are in another language, select the language that would help the students who would benefit from it the most.

There’s no way to turn on the subtitles for every language represented in my class, so I turn on the subtitle in the language that is spoken by the student who needs it the most.

However, pausing alone is not enough. It’s what we have students do during the pauses that fosters comprehension. After stopping the video in the middle, I simply explain the detail we just learned in student-friendly language, and students take notes. Often students take notes using sketchnotes if it is a process, such as with land subsidence. When the content of the video is not a process, such as the Nazi education system, then we take traditional notes using headings and a list of details.

Here’s a video of me modeling intentional pausing.

3. Synthesize the video

By intentionally processing throughout the video, I have significantly raised students’ chances of understanding the content. However, to take this lesson from good to great, we can go a step further by having students synthesize the information. Without synthesizing, students just have a cloud of specific details that float around without taking a specific form or space.

To scaffold the synthesizing process, I have students write a quick paragraph about the content using their notes. Often this is done collaboratively to both increase engagement and raise comprehension as some students will know details that others might not. I usually will sit with a group to support their synthesis by using a series of sentence starters, such as:

• Land subsidence is when…

• Wet clay can…

• Dry clay cannot…

• Farmers pump ground water to…

• As a result…

Videos can be great teaching tools

Videos are educational gold. There’s so much we can learn from videos, and they can be a highly effective and engaging way to teach abstract content. Helpful illustrations and animations from TV and web snippets increase the comprehensibility of the academic content.

To make the best use of explainer videos, make sure to pause periodically to chunk the content. During the pauses, invite students to engage with the content by taking notes. Finally, have students synthesize the information so that details form connections and remain with them for years.

Sadly, I haven’t ever been to the British Museum to see the Cyrus Cylinder in person, but the videos I watched as a young school kid let me know why it was important and to make the visit if possible.

Hurray! I’m so glad that low tech has not been forgotten. Thank you for bringing the use of video back into the classroom.

I used to roll the TV on a cart down the hallway to classrooms when I was an instructional coach in the early ’90s. I always taped the objectives on the TV stand so both students and teachers didn’t think we were just going to watch a movie! I really believe that the video segments I chose to show leveled the playing field, especially for students that lacked that particular background knowledge.

I learned all about this segmented viewing at a Maryland Public Television workshop, where we participants later presented such strategies at their MPT Conference for teachers. I liken this viewing strategy to the Before-During-After Strategy we use daily in the teaching of reading. Thanks for bringing back a good thing!